71 years later, Tennessee and Kentucky still fight over the 1950 football national title

Gen. Robert Neyland beat a young "Bear" Bryant in a whiskey-soaked stadium on the coldest November day in Knoxville history.

And that was merely a subplot to the 1950 Kentucky-Tennessee football game that featured 18 turnovers, kickstarted an iconic broadcaster’s career and led both schools to claim a national championship that the NCAA says neither won outright.

Tennessee (4-4, 2-3 SEC) plays at No. 17 Kentucky (6-2, 4-2) on Saturday (7 p.m. ET, ESPN2) in their 117th meeting since 1893. They have split the last four head-to-head games in one of the most competitive periods of a series the Vols have dominated.

The crossroads of this rivalry came 71 years ago, when No. 9 Tennessee won 7-0 over previously unbeaten No. 3 Kentucky. It catapulted the Vols to a national championship a year later, but the Wildcats were never that good again.

“It was a perfect day for a funeral,” the Louisville Times reported in 1950 on Kentucky’s only loss in its best season ever.

BOWL PROJECTIONS: Sizing up UT's likeliest bowl destinations as Kentucky looms

ADAMS: Is Phillip Fulmer a Vol for Life or Vol for Money? Reader opinions are mixed

Books, newspaper archives and school yearbooks paint a colorful account of the game that turned the programs in opposite directions and the frozen wartime setting in which it was played.

Warmed by Army surplus and resold wool caps

It wasn’t immediately called the Great Appalachian Storm of 1950. That title didn’t come until after 160 died in the East and Northeast from a blizzard with hurricane winds.

The winter storm was merely a distraction from headlines of the Korean War. In Knoxville, it served as the backdrop to a marquee SEC matchup with national title implications.

On Nov. 25, 1950, the 45,000 fans who braved frigid conditions at Shields-Watkins Field knew what they faced. Knoxville hit a record low of 12 degrees the day before the game. It dropped to 5 degrees hours before kickoff, which still stands as the coldest November day recorded in Knoxville.

Fans came prepared, mostly with military ingenuity.

Thousands were wrapped in olive green blankets, which had not yet traveled from the local Army surplus to the front lines in Korea. Air Force pilots wore wool-lined leather flying suits. And veterans covered their upper body with gas capes, designed to survive chemical warfare rather than bitter winds at a football game.

One opportunistic man bought all the wool stocking caps from a dime store on Gay Street and sold them for a steep profit at a makeshift stand beside the stadium gate.

Scalpers in front of the Farragut Hotel took heavy losses, selling tickets that had been priced at $40 before the storm to just $1.50 on gameday.

Where’d all the whiskey go?

Loyal fans huddled around kerosene lanterns and oil stoves, and someone built a bonfire under the stands. Others walked laps to stay warm as police struggled to keep the aisles clear.

“The weather was so cold that fans couldn’t sit still for long. They wandered about the stadium throughout the game,” the News Sentinel reported. “Police reported several parents had to leave the game with their children when the youngsters started crying with cold feet.”

But the lack of alcohol was a bigger concern to shivering fans.

Bootleggers were a couple of hours behind on whiskey deliveries, but they expected to be restocked by Kentucky fans bringing a surplus of booze. When weather delayed their trains, Kentucky fans arrived at halftime with luggage in hand but not less alcohol than expected.

“Kentucky fans used up their stocks on the train,” one Kentuckian quipped to a News Sentinel reporter.

Whiskey finally arrived in the second half, and it flowed freely throughout the stadium. But the crowd was well behaved. Only one drunk fan was arrested, but that had a happy ending.

“He had passed out,” the News Sentinel reported. “They carried him to the police wagon and turned on the heater.”

Maybe ‘Bear’ Bryant should’ve worn long johns

In 1950, Bryant was just 37 years old with a turnaround at Texas A&M and a legendary career at Alabama still ahead. But he had guided Kentucky to a 10-0 record and needed to finally beat Neyland, his nemesis, and the 8-1 Vols for a perfect season.

But Tennessee gave Bryant heartburn like no other opponent.

“I lost my breakfast regularly before the Tennessee game,” Bryant said in “Coach,” a biography by Keith Dunnavant. “Everybody thought Neyland had a jinx on us. It was no jinx. He was a better coach, and he had better football players — and I couldn’t stand it.”

Perhaps out of toughness or stubbornness, Bryant inspected the frozen field at Tennessee wearing a light overcoat. Only majorettes in the Tennessee band, who wore shorts in the halftime show, had more guts.

Bryant’s players followed his lead, declining to wear long johns or high socks. Three weeks earlier, Florida players wore layers of warm clothes under their uniforms during a cold game at Kentucky, and Bryant thought it made them slow.

Bryant also had Kentucky players wear navy blue uniforms against the Vols because they were in Columbia blue when unranked Tennessee upset them a year earlier for their only SEC loss.

Neyland was more practical and less superstitious.

His Tennessee players wore thick black stockings above their knees. And equipment managers brought heating pads into the huddle during every timeout to warm players’ hands.

The Wildcats did neither, and their icy hands suffered for it.

The catch that crushed Kentucky’s dream season

Snow was shoveled off the field, but the game was still sloppy. The teams combined for 20 punts, 18 turnovers and only 17 first downs in the Vols’ 7-0 win.

The Kentucky yearbook reported that “had the Cats been able to hold on to the ball, it might have been a different story.”

That was an understatement. Kentucky lost eight fumbles and All-America quarterback Vito “Babe” Parilli tossed four interceptions against Tennessee’s swarming defense, including one on the Wildcats’ final play in a last-gasp drive inside Vols’ territory.

Tennessee lost four fumbles and threw two interceptions. But in the second quarter, its punt struck a Kentucky player’s leg while he was lying on the ground after a pancake block.

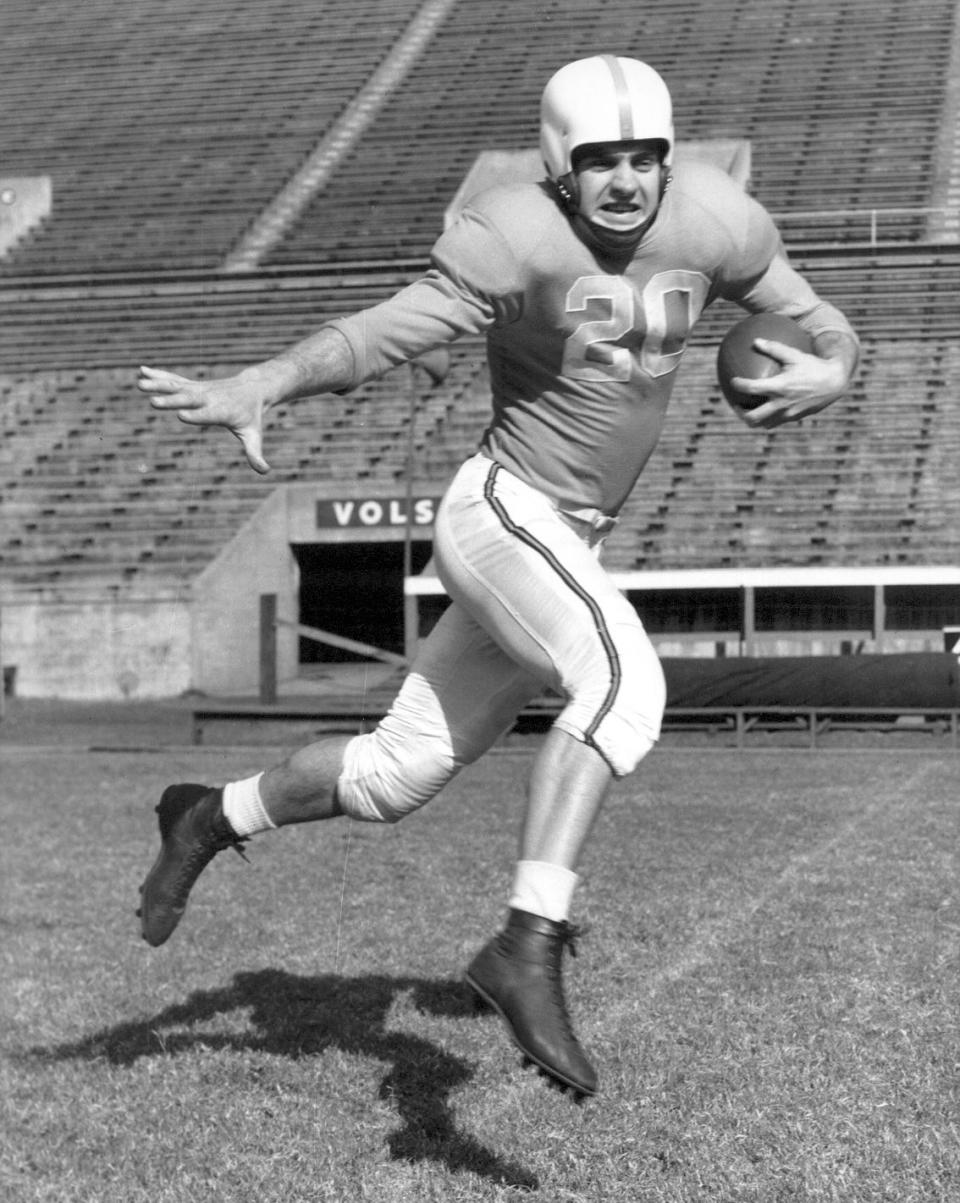

The Vols recovered the ball, but their drive stalled. Then on fourth-and-long, All-American Hank Lauricella fired a pass to Bert Rechichar in double coverage in the end zone. He snagged it for an acrobatic 27-yard touchdown catch. Pat Shires made the PAT kick, and that score held.

The Tennessean wrote that the touchdown turned Kentucky’s dream season into “a Tennessee nightmare.”

Three years later, Rechichar topped that improbable score as a member of the Baltimore Colts.

Despite playing defensive back, he was pressed into duty as a placekicker late in a game. On the first attempt of his career, Rechichar drilled a 56-yard field goal, which stood as the NFL record for 17 years. He continued kicking the rest of his 10-year NFL career.

For a day, the nation listened to Lindsey Nelson

Rechichar’s touchdown and countless defensive stands were superbly called by Lindsey Nelson, then a 31-year-old relatively unknown play-by-play announcer who had recently started the Vols Radio Network.

The game’s high stakes drew a national audience with newsreel cameramen fighting a whipping wind atop the press box and syndicated columnists wiping frost off the windows between plays.

But Nelson’s smooth baritone delivery never cracked, keeping listeners glued to the game that Liberty Broadcasting Network paid $500 to air.

Nelson, a Tennessee graduate, had been tested by much worse than bad weather.

Five years earlier, he had finished active duty as an Army captain in World War II after liberating a Nazi concentration camp, marching toward Berlin and earning seven battle campaign medals and a Bronze Star.

Nelson’s work in the Kentucky game made such an impression that Liberty signed him to a contract after the season, and he went on to a legendary broadcasting career that earned recognition in the College Football Hall of Fame, Pro Football Hall of Fame and Baseball Hall of Fame.

Who was the real 1950 national champion?

Tennessee beat Vanderbilt the next week and went to the Cotton Bowl to face Texas. Kentucky still won the SEC title and headed to the Sugar Bowl against Oklahoma, but the consequences of its loss to the Vols were apparent.

“Kentucky’s national football championship bid was left a pitiful bit of debris,” the Tennessee yearbook reported.

So why, 71 years later, do Tennessee and Kentucky still claim a share of the 1950 national championship in their media guides?

Back then, the Associated Press and United Press International polls awarded a national title at the end of the regular season. In the NCAA record book, Oklahoma is recognized as the consensus national champion based on those major polls.

A couple of minor polls and retroactive computer ratings recognize Tennessee, Kentucky or Princeton as the national champion, which are mentioned in the NCAA record book.

By today’s standards, they would all have a case, but Oklahoma wouldn’t have a prayer.

Kentucky dropped to No. 7 in the AP poll after the Tennessee game and then beat No. 1 Oklahoma in the Sugar Bowl. The Wildcats finished with an 11-1 record and the SEC title, while the Sooners were 9-1.

Tennessee rose to No. 4 after beating Kentucky. The Vols beat No. 3 Texas in the Cotton Bowl and finished 11-1.

No. 2 Army was upset by a 3-6 Navy team. No. 5 California lost to No. 9 Michigan in the Rose Bowl and finished with a 9-1-1 record. No. 6 Princeton had a 9-0 record and did not play in a bowl game.

Knoxville city council picked a national champion

In 2018, undefeated Central Florida was kept out of the College Football Playoff. So, led by current Tennessee athletics director Danny White, the Knights named themselves the national champion.

It wasn’t a new idea.

Sixty-seven years earlier, on the morning after Tennessee’s Cotton Bowl win, the Knoxville city council passed a “national champs” resolution, the News Sentinel reported. It named “the scrappy heroes of the Cotton Bowl the top team in the land.”

Tennessee was convinced that wins over Kentucky and Texas earned its first national title, and the Volunteer State brimmed with pride.

Gov. Gordon Browning had confidently bet Lookout Mountain against the Texas governor’s wager of the Brazos River that the Vols would beat the Longhorns.

“I understand there’s not much water in the Brazos right now, so it won’t be too much trouble to move it to Tennessee,” Browning boasted in the News Sentinel.

Tennessee Vols, UK Wildcats went in opposite directions

Tennessee’s Cotton Bowl victory parade was delayed when the Army took the team’s train to use for troop movements. But a year later, the Vols celebrated a consensus national championship — coincidentally after losing the Sugar Bowl but finishing the regular season ranked No. 1.

Tennessee’s most impressive win during that 1951 national title run was a 28-0 rout of No. 9 Kentucky. Neyland retired after the 1952 season. He never lost to Bryant, who left for Texas A&M a year later.

Within a decade, the Vols started a 50-year dominant stretch over the Wildcats. And Tennessee has won nine SEC titles since then.

Kentucky has captured one SEC title in the past 71 years. And it never won more games in a year than that 1950 season that was spoiled by Tennessee and its iconic coach on a frigid field in November.

Reach Adam Sparks at adam.sparks@knoxnews.com and on Twitter @AdamSparks.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Tennessee, Kentucky still fight over the 1950 football national title