After 8 Months, Cities And States Are Still Sitting On Rental Aid

As President Joe Biden’s administration steps up the pressure on cities and states to distribute billions of dollars in rental assistance, aid for those who need it most has been stuck in a messy tangle of local government systems, often making it too complicated to access.

With a national ban on evictions gone and a more targeted moratorium on evictions in legal limbo, governments at all levels are injecting more urgency into getting federal rental assistance to struggling Americans.

The amount is significant: $46.5 billion, a sum that nearly matches the entire annual budget of the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

States, counties and cities with populations of at least 200,000 were eligible for the money, which offers up to 15 months of rental assistance to low-income individuals (12 months of past-due payments and three months for the future).

But that money has been incredibly slow in getting to the people who need it the most. Through June, only 15 states and the District of Columbia had spent 10% or more of their Emergency Rental Assistance Program funds, which were initially approved by Congress in December.

And in roughly 40 states, counties and cities, not a single cent from ERAP made it out the door during that time, according to an analysis of Treasury Department data by HuffPost. Some of those places were smaller counties, but others were states (New York at $801 million) or territories (Puerto Rico at $325 million) sitting on hundreds of millions of dollars.

The problems stem partly from the fact that Congress has never thrown so much money at an anti-eviction program, so officials at lower levels of government have struggled to find their footing.

“In most cases they couldn’t scale up an already-existing program, or if they could scale up an existing program, that program was tiny compared to the funding available now,” said Ann Oliva, a housing policy expert at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “That explains some of the lag.”

HuffPost reached out to every area that hadn’t handed out any ERAP money through June. The ones who responded cited the difficulty of getting a new program off the ground, inter-governmental coordination struggles, burdensome requirements and even trouble attracting applicants. Many of them also stressed that they have been sending out other housing assistance funds, and others have managed to get their programs up and running in July and August.

HuffPost readers: Facing eviction and struggling to get emergency rental assistance? Tell us about it ― email arthur@huffpost.com. Please include your phone number if you’re willing to be interviewed.

But plenty of governments were able to do it. Advocates say that some who couldn’t were trying to conduct business as usual instead of recognizing the emergency of the moment. And in many cases the culprit has been too much paperwork.

“The fact that some places are doing a really good job of spending down their resources shows that really any city and state can be doing this and that there’s no excuse for not getting this money out the door,” said Sarah Saadian, vice president of public policy at the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

The New York Mess

Among the most galling instances of a slow ERAP response is the state of New York. According to the Treasury Department’s data, New York was the only state that sent out no federal rental assistance through the month of June ― even though it has the most renters in the country.

The state didn’t open the application process until June 1. Payments weren’t issued until more than a month later, on July 19.In the last couple of weeks, the state has begun to ramp up the program, disbursing tens of millions of dollars in a matter of days.

But the system was a mess. The initial application process was lengthy and full of technical glitches. It was unclear what documentation applicants needed to be eligible, and the website would time out before they were able to properly submit their forms, forcing them to start over again.

“The main the reason is that the application was fucking impossible,” said Bill Neidhardt, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s spokesperson. “I think it’s strategic incompetence. That’s why they delayed it, and that’s why they rolled out a mind-bogglingly unusable interface. Both those things show they didn’t want people to get the money.”

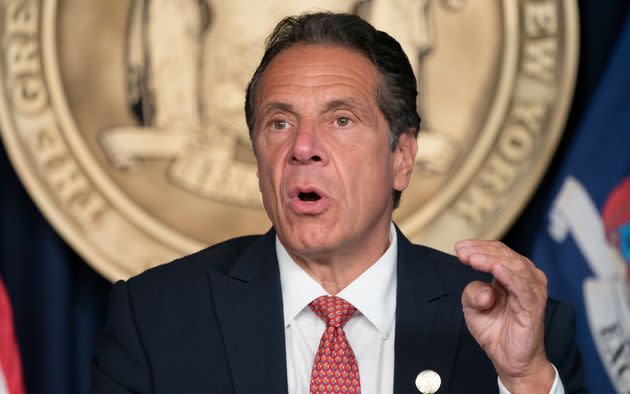

The state rejects those characterizations. Jim Urso, a spokesperson for Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s office, said it was “simply not true” that the funding was being held hostage by the state. The state gave priority to low-income or unemployed individuals for the first month — 100,000 people applied in the state in June. Cuomo ― who said Tuesday that he is resigning, under a cloud of sexual harassment allegations ― announced a more streamlined application process in mid-July.

More than 830,000 households are behind on rent in the state, with a total debt of more than $3.2 billion, according to an analysis by the National Equity Atlas, a research group associated with the University of Southern California.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) has been calling out his state. He held a news conference in Hells Kitchen in New York City late last month, and for two days in a row on the Senate floor last week, Schumer again criticized New York, saying he was sending a letter to state officials asking them to start doing a better job.

Federal Pressure Steps Up

The Biden administration decided not to extend the nationwide moratorium that expired at the end of July, worried it would not survive legal challenge. After pressure from many of his Democratic allies, he announced a more limited 60-day ban in counties with elevated rates of COVID-19.

As the White House and congressional Democrats blamed each other for letting the moratorium lapse, federal leaders all seem to agree that local governments dropped the ball on dishing out the money.

“The problem has been with state governments who have been pathetically slow to get the money out,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said last week.

The Treasury Department, which runs the program, sent a letter to all the states, counties and cities that hadn’t disbursed any ERAP money through the end of June, according to a department official. It has also been trying to get the word out about the money through urban and Spanish-language radio, and by providing more information to religious and community organizations. And it has been underscoring an effort to reduce documentation burdens to make it easier to apply for assistance.

Awareness of the program has been lagging. A May poll from the Urban Institute found that more than half of renters and 40% of landlords were unaware of the federal rental aid.

Chicago hadn’t distributed any of its $80 million in ERAP funds through the end of June, although the city had been distributing other assistance. Eugenia Orr, spokesperson for the Chicago Department of Housing, said that the city’s ERAP application process opened at the end of May but her office had to wait for the City Council to allocate the funds before the agency could start spending them.

“Bureaucratic bungling is unacceptable,” said Rep. Bobby Rush (D-Ill.), who represents the city. “I am astounded and heartbroken that my constituents, who are suffering from horrendous economic woes in the midst of an ongoing pandemic, have not received the full financial relief that I voted for. Chicago should be the beacon light that others follow — not a bench warmer.”

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) also gave a speech on the Senate floor, talking about a constituent named Patricia Vasquez, who received an email on July 23, telling her she qualified for ERAP funds. But if the money had come earlier, he said, some of her hardship could have been averted.

“[T]he gas to her apartment had already been cut off because of a $1,400 unpaid bill. She had sold some of her clothes and jewelry to pay the electric bill and keep the lights on, and she was six months behind in rent. The emergency assistance will help her pay rent and utility bills,” Durbin said.

“I think there are a lot of members of Congress who maybe didn’t realize just how slow it’s been to get emergency rental assistance out, because we’ve seen a lot of members voice a lot of frustration at how slow things have been,” Saadian said. “Some of them have reached out to us about finding ways ― how can they be communicating with our program to encourage them to adopt these best practice.”

Challenges At The Local Level

Many of the places that have been slow to get the program off the ground cited challenges in dealing with technological issues, training staff to administer the program, finding partners to work with on this project and trying to navigate federal rules.

But paperwork has been a major impediment.

The Treasury Department has tried to ease the documentation burdens in order to get money to people as quickly as possible, a move that was widely praised by housing advocates. Last week, the department published examples of simplified eligibility forms that areas could use.

But not every place has gone along with that model, and officials say they’re just doing their due diligence. Dori Henry, deputy chief of staff for the Baltimore County executive, said that, despite the Biden administration’s efforts to make the process easier, the county “must still be a good steward of taxpayer dollars and ensure that it is providing assistance to those households who are actually eligible.”

“A lot of the times what we’ve seen is that state and local governments aren’t using all of the flexibility that Treasury’s given them,” Saadian said. “And instead they’re putting in place their own documentation requirements or very lengthy application processes, which are getting in their own way of distributing aid.”

Combining resources at the state, city and county level has worked well in many places. Houston and Harris County, Texas, have become a model, with the city and county pooling resources and pulling together grassroots groups to help people fill out applications.

Barbara Canales, county judge in Nueces County, Texas, said its delay was rooted in the fact that the county’s administrative allotment of funds was rather small ($1.1 million), and the county eventually realized that by partnering with the county seat, Corpus Christi, it would be able to get going. It launched the program on July 22.

Many places that have opened applications for ERAP money have been flooded with requests. Los Angeles, Phoenix and the state of North Carolina were all overwhelmed with requests when they opened their programs.

But others say it’s been a challenge to get people to apply.

“This has been really slow,” said Jaime Longoria, director of the Hidalgo County, Texas, Community Service Agency. “It’s surprisingly slow is how I would characterize it.”

Longoria said his county launched its ERAP application process in April, yet by the end of June, it still hadn’t given out any money (although it had been assisting families with other funds since the start of the pandemic). He worried that people weren’t applying for aid in part because they were nervous about how it would affect their immigration status down the road.

Tom Arnone, a county commissioner in Monmouth County, New Jersey, also cited landlord-tenant cooperation as one of the biggest frustrations.

“One of the most challenging and time-consuming aspects of administering this type of federally funded, tenant-focused grant program is the coordination of both tenants and landlords during the application process,” he said.

Philadelphia, listed on the Treasury Department’s chart as having distributed zero dollars, said it had actually doled out $40 million worth of ERAP funds, but the sum is omitted from the department’s total because the money came to the city circuitously, though a state appropriation. The city says it has actually disbursed $128 million in rent and utility assistance.

“Please note that we will run out of federal money long before we run out of tenants who need it,” Philadelphia Department of Housing and Community Development spokesperson Jamila Davis said in an email.

Philadelphia’s approach has been a relative success thanks in large part to an April court order requiring landlords to apply for rental assistance before they file for eviction. The U.S. Department of Justice has urged other state and local courts to follow Philadelphia’s example.

States and localities are also running up against a deadline. If they don’t use at least 65% of their allocated funds by the end of September, the federal government has the authority to take them back.

That urgency, Saadian hopes, will push governments to get the money out.

“The people who are most likely to be harmed by these evictions are people of color because of preexisting racial inequities in the housing market and because of the impact of the pandemic and the economic fallout,” she said. “And that’s going to have really long-term impacts on individual households stability, but also racial inequity community-wide.”

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.