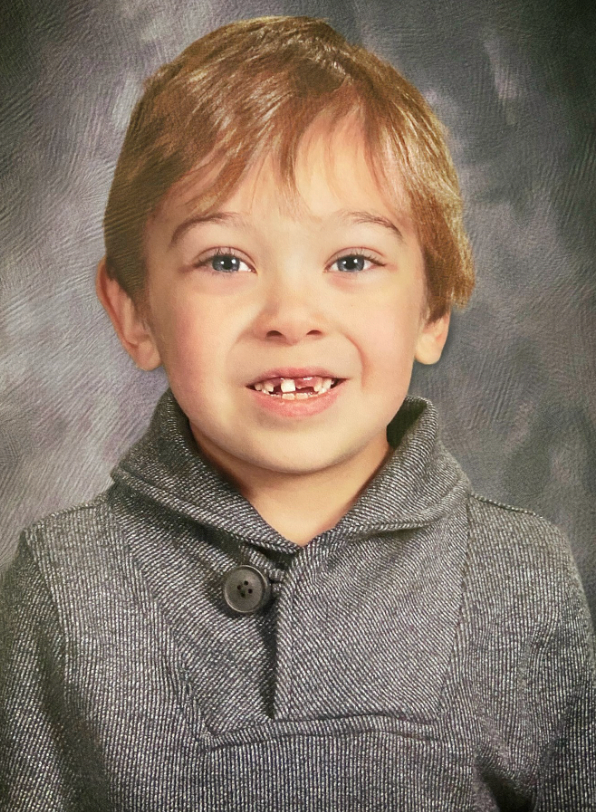

8-year-old died in agony at Norton hospital after life-sustaining care withdrawn, suit says

As The Courier Journal often writes, claims made in filing a lawsuit only present one side of the case. But the claims made in a suit filed in July against Norton Healthcare by Chris and Sally McCullum on behalf of their son Finnley may make you cry.

“What a terribly sad story,” said Steve Joffe, chairman of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania.

Finnley was born in 2014 with a congenital heart defect that he struggled with the rest of his life, undergoing five open-heart surgeries and numerous hospital stays, including one that consumed the final year of his life.

But in an obituary, his parents say he loved life and exuded “pure joy and happiness.”

He adored spicy food — the hotter, the better. He loved creepy and scary stuff, like a typical 8-year-old, and cranking up everything from the Beatles to BTS to rapper Tay-K on his music system.

Most of all, Finnley enjoyed spending time with his parents, whether it was a trip to the zoo, Walt Disney World or simply a walk in a stream exploring the world around him.

His last best hope for a healthy life was a heart transplant last year, but his body rejected it after just a few hours.

At the recommendation of his treatment team at Norton Children’s Hospital, he was kept alive for 8½ months with a ventilator, dialysis and a “bridge heart," until he could undergo another transplant, his parents say.

But the McCullums say in their suit filed in Jefferson Circuit Court that Norton told them in April that Finnley had been removed from the transplant list. And they allege that a few days later, the hospital “unilaterally” decided to withdraw life-sustaining medical treatment, meaning Finnley would die.

The McCullums also allege Norton promised Finnley would experience no pain or fright as his care was withdrawn. But they say their child spent his last hour on Earth in fear and agony, desperately calling out for his parents to help him.

They say they could only assure him — falsely — that everything would be all right. He died April 19.

Responding to the suit in court papers, the hospital company acknowledges the McCullums "will live with the sadness anyone feels when they have lost a child to untreatable illness.”

But in court papers, Norton says the couple has its facts wrong.

It says Finnley never was on the list for another transplant, once the first one failed.

Norton also denies it made a unilateral decision to end Finnley’s life, saying the hospital's ethics committee helped make that call.

And Norton says it acted legally and ethically when it withdrew care for Finnley once his treatment team determined his case was hopeless and prolonging care would not benefit him.

The hospital says it also gave his parents the chance to seek a court order blocking its decision, but they elected not to seek one.

The McCullums' lawyer, Ann Oldfather, said in an interview they wanted to spend Finnley’s remaining time with him rather than in a courtroom.

Medical authorities who reviewed the case for The Courier Journal said Norton acted appropriately and that it might been unethical to continue care that was futile.

“I don’t think there was any more anyone could have done,” said Arthur Caplan, director of the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University. “It was pretty hopeless. You can’t restore a heart without a transplant.”

Bruce Jennings, director of bioethics at the Center for Humans and Nature and adjunct associate professor of health policy at Vanderbilt University, said Norton should have given Finnley parents the option to move him to a hospital that would continue his care. Citing privacy laws, Norton has declined to comment on the case.

But Norton’s care of Finnley seems to have been consistent with its own policy and the American Academy of Pediatrics standards that call for promoting the comfort and dignity of children at the end of life.

While the latter organization, which has 67,000 members, says the treatment of pediatric patients is generally rendered under a presumption of sustaining life, it says sometimes the balance of benefits and burdens to the child leads to an assessment that “forgoing life-sustaining medical treatment is ethically supportable or advisable.”

Norton’s policy, which it provided to the newspaper, says a patient’s attending physician may withhold life-sustaining treatment if it is “non-beneficial” — that it serves to prolong life without reversing the underlying medical condition. But the policy says the patient or his parent must be given the chance to transfer care to another hospital or to go to court to challenge the decision.

“Children will sometimes die despite our best efforts, and we run the risk of compounding that tragedy when we lack the courage and wisdom to recognize the limits of our technology,” say a dozen pediatric experts in “Guidance for Forgoing Life-Sustaining Medical Treatment,” published in ‘Pediatrics,” a professional journal.

“A misguided effort to 'save' a child can easily rob her of the opportunity to be touched and cared for by those she loves, to say goodbye, and to be held by those who love her without the distraction of overly burdensome interventions. We can too easily forget that the patient and not the disease is the object of our care.”

Withdrawing life-sustaining treatment for children is not unusual.

As many as 60% of children who die in pediatric intensive care units do so after a decision to withdraw or limit treatment, according to a study published by the National Institutes of Health.

No date has been set yet for the trial of the McCullums' lawsuit, which asks for damages for trauma it says were inflicted on Finnley and his parents.

The case may turn on whether Norton properly sedated Finnley before his treatment was withdrawn.

In its written response to the suit, Norton’s lawyer, Beth McMasters, says “sedating medications were given and effective.”

But her response also suggests Finnley’s parents interfered with the sedation.

“Had plaintiffs allowed administration of the ordered sedating medications ... their decedent would not have had any awareness of any of the process.”

McMasters declined to elaborate on the discrepancy, saying Norton executives decided not to comment on the suit unless the McCullums waived Finnley’s privacy rights. Oldfather said they would not do that because it was legally unnecessary.

The McCullums did “everything they could to protect Finnley" from knowing what was happening, Oldfather said. Asked what they miss most about him, she said, “Everything.”

She said the McCullums didn't want to be interviewed about this story because they were still too upset about Finnley's death.

More: Anxiety after the pandemic? Thousands of JCPS students 'chronically absent' from school

Finnley lived in Louisville and New Albany, Indiana, where he attended Grant Line Elementary School. He is buried at Holy Trinity Catholic Cemetery in New Albany, Indiana.

In their obit for their son, the McCullums said Finnley will be deeply missed, and his memory will be cherished by many,

“He was a brilliant and pure light," they said, "shining innocence and love. He made our world a better place.”

Reporter Andrew Wolfson can be reached at (502) 396-5853 or awolfson@courier-journal.com.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Norton Children's Hospital sued over withdrawal of boy's life support