8 strains of the coronavirus are circling the globe. Here's what clues they're giving scientists.

SAN FRANCISCO – At least eight strains of the coronavirus are making their way around the globe, creating a trail of death and disease that scientists are tracking by their genetic footprints.

While much is unknown, hidden in the virus's unique microscopic fragments are clues to the origins of its original strain, how it behaves as it mutates and which strains are turning into conflagrations while others are dying out thanks to quarantine measures.

Huddled in once bustling and now almost empty labs, researchers who oversaw dozens of projects are instead focused on one goal: tracking the current strains of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that cause the illness COVID-19.

We're sending daily coronavirus updates: Get USA TODAY's Daily Briefing in your inbox

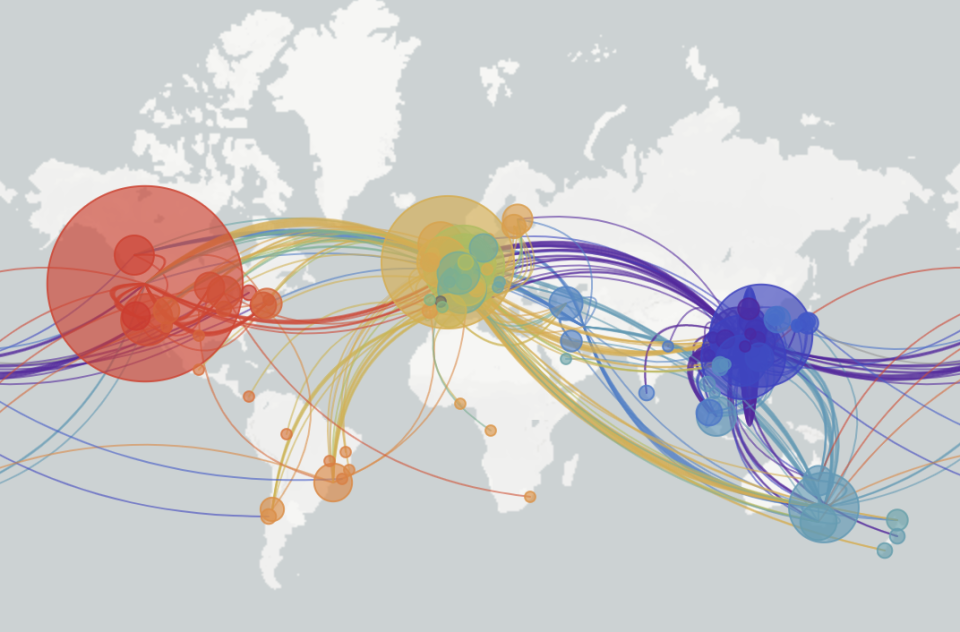

Labs around the world are turning their sequencing machines, most about the size of a desktop printer, to the task of rapidly sequencing the genomes of virus samples taken from people sick with COVID-19. The information is uploaded to a website called NextStrain.org that shows how the virus is migrating and splitting into similar but new subtypes.

While researchers caution they're only seeing the tip of the iceberg, the tiny differences between the virus strains suggest shelter-in-place orders are working in some areas and that no one strain of the virus is more deadly than another. They also say it does not appear the strains will grow more lethal as they evolve.

“The virus mutates so slowly that the virus strains are fundamentally very similar to each other,” said Charles Chiu, a professor of medicine and infectious disease at the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine.

Investigation: How federal health officials mislead states and derailed the best chance at containment.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus first began causing illness in China sometime between mid-November and mid-December. Its genome is made up of about 30,000 base pairs. Humans, by comparison, have more than 3 billion. So far even in the virus's most divergent strains scientists have found only 11 base pair changes.

That makes it easy to spot new lineages as they evolve, said Chiu.

“The outbreaks are trackable. We have the ability to do genomic sequencing almost in real-time to see what strains or lineages are circulating,” he said.

So far, most cases on the U.S. West Coast are linked to a strain first identified in Washington state. It may have come from a man who had been in Wuhan, China, the virus’ epicenter, and returned home on Jan. 15. It is only three mutations away from the original Wuhan strain, according to work done early in the outbreak by Trevor Bedford, a computational biologist at Fred Hutch, a medical research center in Seattle.

On the East Coast there are several strains, including the one from Washington and others that appear to have made their way from China to Europe and then to New York and beyond, Chiu said.

Death rate soars in New Orleans coronavirus 'disaster' that could define city for generations

Beware pretty phylogenetic trees

This isn’t the first time scientists have scrambled to do genetic analysis of a virus in the midst of an epidemic. They did it with Ebola, Zika and West Nile, but nobody outside the scientific community paid much attention.

“This is the first time phylogenetic trees have been all over Twitter,” said Kristian Andersen, a professor at Scripps Research, a nonprofit biomedical science research facility in La Jolla, California, speaking of the diagrams that show the evolutionary relationships between different strains of an organism.

The maps are available on NextStrain, an online resource for scientists that uses data from academic, independent and government laboratories all over the world to visually track the genomics of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. It currently represents genetic sequences of strains from 36 countries on six continents.

While the maps are fun, they can also be “a little dangerous” said Andersen. The trees showing the evolution of the virus are complex and it’s difficult even for experts to draw conclusions from them.

“Remember, we’re seeing a very small glimpse into the much larger pandemic. We have half a million described cases right now but maybe 1,000 genomes sequenced. So there are a lot of lineages we’re missing,” he said.

The basics on the coronavirus: What you need to know as the US becomes the new epicenter of COVID-19

Different symptoms, same strains

COVID-19 hits people differently, with some feeling only slightly under the weather for a day, others flat on their backs sick for two weeks and about 15% hospitalized. Currently, an estimated 1% of those infected die. The rate varies greatly by country and experts say it is likely tied to testing rates rather than actual mortality.

Chiu says it appears unlikely the differences are related to people being infected with different strains of the virus.

“The current virus strains are still fundamentally very similar to each other,” he said.

The COVID-19 virus does not mutate very fast. It does so eight to 10 times more slowly than the influenza virus, said Anderson, making its evolution rate similar to other coronaviruses such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).

It’s also not expected to spontaneously evolve into a form more deadly than it already is to humans. The SARS-CoV-2 is so good at transmitting itself between human hosts, said Andersen, it is under no evolutionary pressure to evolve.

Shelter in place working in California

Chiu’s analysis shows California’s strict shelter in place efforts appear to be working.

Over half of the 50 SARS-CoV-2 virus genomes his San Francisco-based lab sequenced in the past two weeks are associated with travel from outside the state. Another 30% are associated with health care workers and families of people who have the virus.

“Only 20% are coming from within the community. It’s not circulating widely,” he said.

That’s fantastic news, he said, indicating the virus has not been able to gain a serious foothold because of social distancing.

It's like a wildfire, Chiu said. A few sparks might fly off the fire and land in the grass and start new fires. But if the main fire is doused and its embers stomped out, you can kill off an entire strain. In California, Chiu sees a lot of sparks hitting the ground, most coming from Washington, but they're quickly being put out.

Get daily coronavirus updates in your inbox: Sign up for our newsletter now.

An example was a small cluster of cases in Solano County, northeast of San Francisco. Chiu’s team did a genetic analysis of the virus that infected patients there and found it was most closely related to a strain from China.

At the same time, his lab was sequencing a small cluster of cases in the city of Santa Clara in Silicon Valley. They discovered the patients there had the same strain as those in Solano County. Chiu believes someone in that cluster had contact with a traveler who recently returned from Asia.

“This is probably an example of a spark that began in Santa Clara, may have gone to Solano County but then was halted,” he said.

The virus, he said, can be stopped.

China is an unknown

So far researchers don’t have a lot of information about the genomics of the virus inside China beyond the fact that it first appeared in the city of Wuhan sometime between mid-November and mid-December.

The virus’s initial sequence was published on Jan. 10 by professor Yong-Zhen Zhang at the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center. But Chiu says scientists don’t know if there was just one strain circulating in China or more.

“It may be that they haven’t sequenced many cases or it may be for political reasons they haven’t been made available,” said Chiu. “It’s difficult to interpret the data because we’re missing all these early strains.”

Researchers in the United Kingdom who sequenced the genomes of viruses found in travelers from Guangdong in south China found those patients’ strains spanned the gamut of strains circulating worldwide.

“That could mean several of the strains we’re seeing outside of China first evolved there from the original strain, or that there are multiple lines of infection. It’s very hard to know,” said Chiu.

There's a new symptom of coronavirus, docs say: Sudden loss of smell or taste

The virus did not come from a lab

While there remain many questions about the trajectory of the COVID-19 disease outbreak, one thing is broadly accepted in the scientific community: The virus was not created in a lab but naturally evolved in an animal host.

SARS-CoV-2’s genomic molecular structure – think the backbone of the virus – is closest to a coronavirus found in bats. Parts of its structure also resemble a virus found in scaly anteaters, according to a paper published earlier this month in the journal Nature Medicine.

Someone manufacturing a virus targeting people would have started with one that attacked humans, wrote National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins in an editorial that accompanied the paper.

Andersen was lead author on the paper. He said it could have been a one-time occurrence.

“It’s possible it was a single event, from a single animal to a single human,” and spread from there.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Coronavirus: How scientists are tracking 8 strains of SARS-CoV-2 virus