8 Wild Examples of Evolution Copying Itself

Sometimes, Darwinian natural selection stumbles upon the same solution more than once, in a process known as convergent evolution. Here are our favorite examples of evolution making the same creature, or same physical trait, twice.

In evolution, mutation is random, but selection is most certainly not. Every adaptive new trait acquired by a species was likely accompanied by countless failed experiments. The judge, as it were, in deciding which mutations are beneficial or not is brutally simple: ongoing survival.

Read more

For organisms caught in a Darwinian mode of existence—which is all of them—the space of all possible beneficial mutations is sufficiently small, a space ruled by physics, biological constraints, and environmental pressures. It sometimes happens that two unrelated species, separated by time and space, will find themselves living in the same ecological niche or facing similar evolutionary problems. When this happens, evolution will dip into its limited grab-bag of solutions—as you can plainly see in these striking examples.

This story was originally published on June 11, 2020.

Dolphins and Ichthyosaurs

The Germans have a great word to describe an ensemble of physical features common to different species: Bauplan. This translates to “body plan” in English, and it nicely encapsulates a key aspect of convergent evolution, namely morphological similarities in unrelated species. In other words, two different animals that look a hell of a lot alike.

Two species that share a common or at least a very similar Bauplan are modern dolphins and ancient ichthyosaurs. It’s a striking example of evolution stumbling upon the same solution for two very different types animals, in this case mammals and reptiles. These two creatures share other similarities as well, including live births, warm blood, and even similar camouflage.

Modern sharks and dolphins share certain aspects of convergent evolution, such as their streamlined shape and triangular dorsal fin, but they also have many differences.

Cassowaries and Corythoraptors

In 2017, paleontologists discovered an unusual dinosaur in southern China called Corythoraptor jacobsi. Dating back to the Late Cretaceous, the bipedal oviratporid was remarkably similar to modern cassowaries, a flightless bird native to Queensland, Australia.

In addition to sharing a similar body shape, both animals feature elaborate crests, called a casque, on the top of their heads, which likely serve as advertisement for prospective mates.

Canids and Tasmanian Tigers

The extinct Tasmanian tiger, also known as the thylacine, looked eerily similar to modern canids, a group of predatory carnivores that includes wolves, foxes, and domesticated dogs. But thylacines were large marsupial predators, and they carried their young in a pouch similar to kangaroos and koalas.

Incredibly, the last common ancestor of placental canids and thylacines lived 160 million years ago, during the Jurassic period. Despite this gigantic gap in evolutionary history, both Tasmanian tigers and canids share a strikingly common skull shape and body plan. As a Nature paper from 2017 pointed out, their physical “resemblance is considered the most striking example of convergent evolution in mammals.”

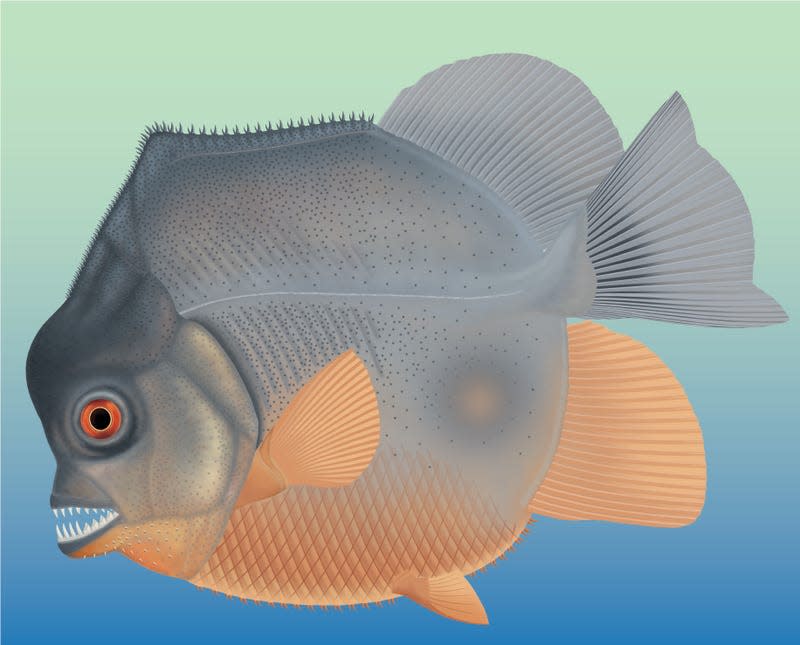

Piranhas and Piranhamesodons

During the late Jurassic, some 150 million years ago, a very piranha-like fish terrorized the seas in what is now southern Germany. Called Piranhamesodon pinnatomus, it’s the oldest known flesh-eating ray-finned bony fish, a family that now includes trout, grouper, and cod, but not modern piranhas.

Piranhamesodon featured distinctly piranha-like teeth, which it used to bite chunks of flesh from other fish—especially from their fins. Paleontologist David Bellwood from James Cook University said it’s “an amazing parallel with modern piranhas, which feed predominantly not on flesh but the fins of other fishes,” to which he added: “It’s a remarkably smart move as fins regrow, a neat renewable resource. Feed on a fish and it is dead; nibble its fins and you have food for the future.”

Undersized Archaic Humans

Paleontological evidence suggests humans aren’t immune to the effects of convergent evolution. Homo sapiens is the last human species left standing, but plenty of other humans have walked the Earth, including Neanderthals, Denisovans, H. erectus, H. naledi, among others.

In 2004, scientists working on the island of Flores discovered evidence of a diminutive human species, called Homo floresiensis, popularly known as the Hobbit. Now extinct, this archaic human stood no taller than 3 feet and 7 inches (109 centimeters). Incredibly, evidence of a second diminutive species, named Homo luzonensis, was uncovered in the Philippines in 2007.

These species lived at roughly the same time—roughly 50,000 years ago—but nowhere close to each other. Their striking physical similarities has been attributed to an evolutionary process known as insular dwarfism, in which a species shrinks over time owing to limited resources. Perhaps not coincidentally, both human species lived on islands, which are known to produce diminutive species of various sorts.

Six-Fingered Aye-Ayes and Giant Pandas

Research from 2019 showed that aye-ayes have a sixth finger, or as scientists call it, an “accessory digit.” Giant pandas also feature an extra finger on top of the usual five per hand. Same for moles and some extinct reptiles, which they use for digging. Like the giant panda, however, aye-ayes use their sixth finger to enhance their grasping abilities, making this a good example of convergent evolution.

Fascinatingly, the accessory digit in aye-ayes and giant pandas is an example of convergent evolution as a consequence of contingent evolution. Both animals evolved highly specialized hands not suited for climbing, resulting in an evolutionary pressure to produce a sixth finger.

Bats and Ambopteryx

Bats, flying squirrels, and extinct pterosaurs have membranous wings held in place by a special bone called the styliform. That’s convergent evolution in action, but dinosaurs also co-opted this strategy, in which wings are formed from webbing around super-elongated fingers. This revelation was only made in 2019, following the discovery of Ambopteryx longibrachium, a tiny Jurassic dinosaur with membranous wings.

Marsupial and Placental Moles

Evolution is incredibly diverse, but at the same time super limited. All species must honor basic physics and unassailable biological limits (we’ll never see, for example, an animal with wheels... or at least we don’t think we ever will). At the same time, evolution often drives animals toward common “fitness peaks,” in a phrase used by evolutionary biologists. And sometimes, those fitness peaks just happen to be located at the very same spot.

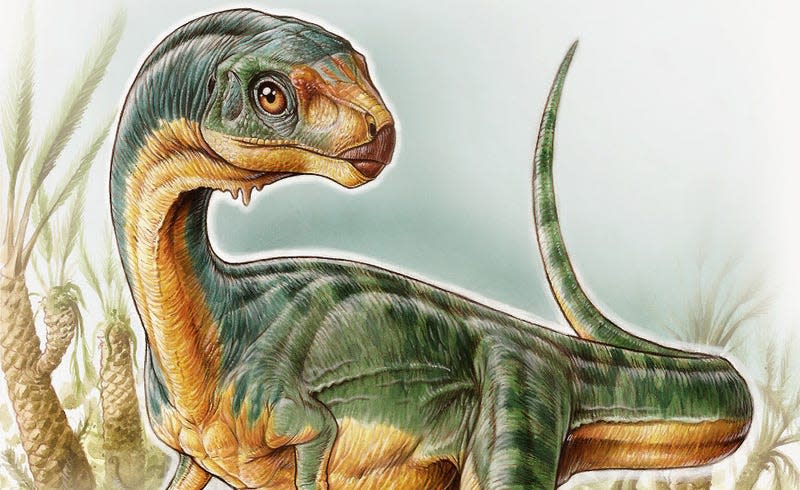

The ‘Platypus’ Dinosaur

When this remarkable theropod, called Chilesaurus diegosuarezi, was revealed to the world in 2015, its discoverers called it the “platypus” of dinosaurs owing to its patchwork of anatomical features.

This creature is a stunning example of mosaic convergent evolution, in which characteristics seen in several unrelated species are lumped together to create... well.... a kind of platypus-like creature. In this case, Chilesaurus had strong forearms like Allosaurus, and a pelvis similar to ornithischian dinosaurs, such as Stegosaurus and Ceratopsians. It also featured teeth, skull, a facial features seen in other dinosaurs.

More from Gizmodo

Sign up for Gizmodo's Newsletter. For the latest news, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.