In the ’80’s, his book ban fight went to the Supreme Court. Does it compare to Beaufort Co. today?

Nearly 40 years ago, a concerned neighbor went up to Steven Pico’s mother and said: “I’m so sorry. Steve must’ve done something horrible, like killed someone, to get on the front page of the paper,” according to Steven.

It wasn’t that: he was suing the school district.

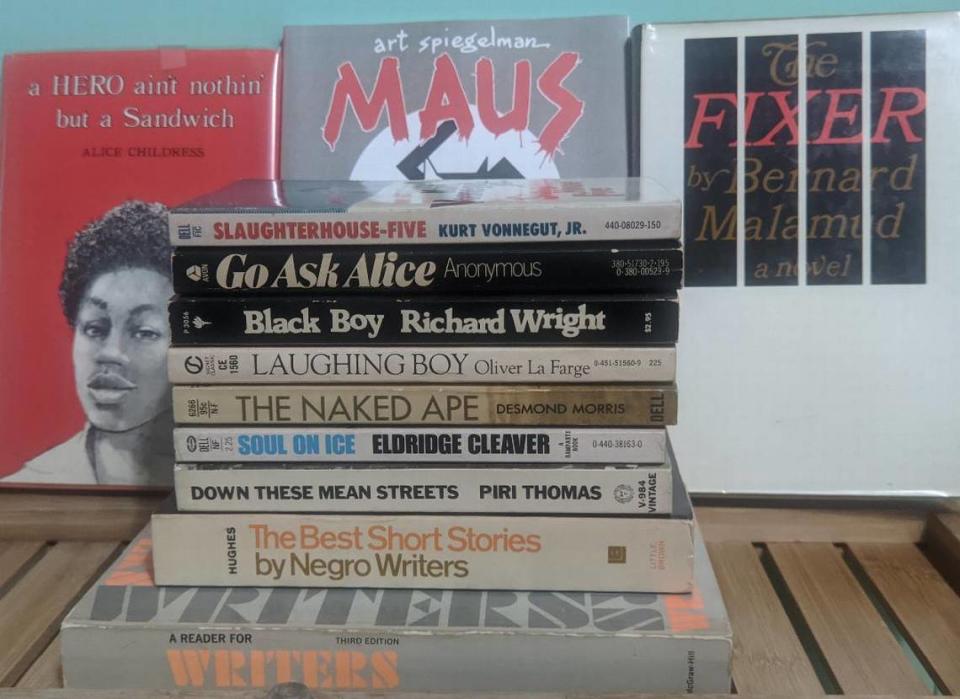

In 1976, Pico and four other teens sued their Long Island school district for banning 11 books from their classrooms and school libraries. It is the only book-banning case that has gone to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Hundreds of miles away in South Carolina and about four decades later, Beaufort County made local and national headlines by pulling 97 books off classroom and library shelves for review. The district has since reviewed 66 and banned four. No one has brought up lawsuits against the county regarding the banned books yet.

It’s a nationwide tend. Across the United States, the American Library Association found 1,269 attempts to censor library books and resources from public schools and libraries in 2022. They said it was the highest number of attempted book bans since they began compiling data about censorship in libraries more than 20 years ago. The number 2022 doubles the 729 challenges reported in 2021.

Beaufort County resident and Beaufort Academy student Elizabeth Foster, 18, who graduated last school year was at the forefront of the local opposition to book bans. BA isn’t part of the public school system, but Foster attended school board meetings, forums and organized events to advocate against the district keeping books off shelves.

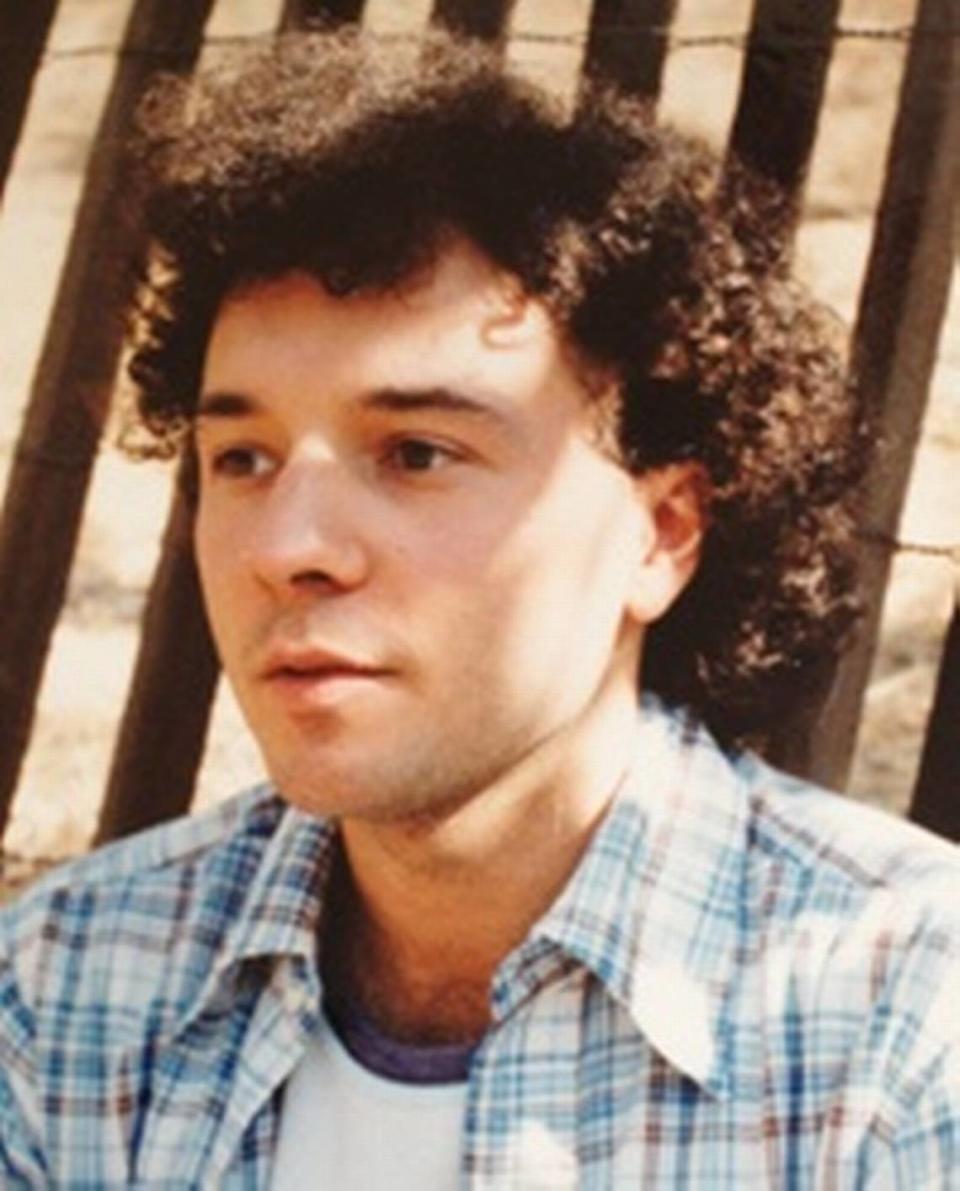

Pico, 64, spent six-years battling against his school district until the U.S. Supreme Court held that public schools cannot remove books from school libraries because of their content under the First Amendment. He still lives in New York and is a painter, sculptor and editor. In his free time he advocates for first amendment rights, including connecting with students like Foster on how to fight back against book bans.

“When you’re young, you can be fearless,” Pico said. He sat down with Foster and The Island Packet and Beaufort Gazette to compare his experience as a young person fighting book bans in Long Island years ago to Foster’s experiences in Beaufort County last year.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Where did the movement to ban books come from?

Steven Pico: The major difference between now and then was that then book banning was coming from many quarters in our culture. There were many feminists who wanted to engage in censorship. There were Black people who came up to me and said “I don’t want ‘Gone With the Wind’ shown in my school. I don’t want ‘The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ taught.” I had to confront censorship from all parts of the culture. It was also the time of the rise of the Moral Majority.

Today, you have Republican governors who have to be called out for encouraging people to censor. And they encourage it in ways that are just simply unfair. Not encouraging people to read the books, just encouraging people to pass out excerpts, words, and say, “This is vulgar.”

Elizabeth Foster: The list of books pulled from Beaufort County schools list attacks so many different cultures and identities, that there’s really only one culture left over that’s not being attacked. And that’s the kind of people that are making these complaints and filing those complaints.

How political do you think the book ban movement is?

SP: We don’t see this as a right wing, left wing issue. We see this as a patriotic issue. I don’t want to speak for Elizabeth, but we see this as something that everybody should be fighting against from all parts of the political spectrum. So we definitely agree with that. We think this is a mainstream issue that goes to the heart, the bastion of our democracy, of multiculturalism, of pluralism.

There are haters and extremists throughout the country. I think that the majority of book banners today are the new bullies on the block. Politicians who encourage attacks on literature, educators, librarians and our institutions devoted to learning are nothing more than opportunists who are fanning the flames of hatred and division for selfish political gain. So this is the first time in 45 years of advocacy that I’m saying: We have to also address the political aspects of this.

Most newspapers don’t want to print that the majority of censorship is being flamed by the Republican Party, or at least part of the Republican Party. It’s definitely Republican governors, right now. They don’t want to lay political blame, when in fact, we need to lay political blame, because Republicans who are not happy with censorship, need to perhaps think about leaving their party and returning when these attacks on our liberty stop.

EF: I think that this is definitely much more targeted, streamlined. It’s very organized. It’s not a rise of censorship across groups nationally, it’s a rise of censorship by groups like Moms for Liberty, and by the GOP.

Did you feel supported by your community to speak up against book bans?

SP: I didn’t have a lot of support either at the family level or at the community level and honestly, I didn’t care. My parents were not totally supportive because they were worried that I would be labeled a troublemaker: that my name and my reputation would be harmed, that I would have trouble in school, in getting into college.

The teachers and librarians were supportive privately, so there was a lot of whispering, and that as a student annoyed me.

EF: I feel really supported by my community, my family. I know teachers are in a difficult position in offering their support, just because in the climate, you know, it’s difficult. But they did at school. I think that from my peers, I experienced a lot of apathy more than anything. So it wasn’t necessarily disapproval, or anger at me, it was just like, it wasn’t even on their radar, which is understandable, as a high schooler, and sometimes frustrating.

Did you ever feel scared?

SP: (No.) I don’t understand the need for raising this to a level of threats and violence and hatred. Today, young people already face violence, hatred, bullying, drug and sexual abuse issues. I want them to be prepared. There are sincere parents who have concerns. Book banning, in my opinion, in my experience, leaves young people defenseless.

You can always donate or suggest that we add literature to balance our curriculum to balance a classroom discussion. And the whole point of this, I think, is that parents and everyone else in our society need to remember that schools and libraries are one of the few safe places, supervised places. There are usually security guards. It’s a safe place where there’s somebody to lead discussion: a teacher, or librarian, educator. And students, if they wish, can discuss things among their peers.

EF: Our first kind of, I guess, frightening interaction was at that one board meeting when the the speaker broke the rules by calling out one of my friends. The board recessed and then she turned around and again, began delivering her speech in an aggressive manner towards us, because we were in the front row. That was scary for me.

How did you think social media played into you feeling frightened?

EF: I personally am not on Facebook. I don’t interact with the complainants on social media. But I know that there are a lot of efforts from them to interact with my friends and the Families Against Book Bans. There’s just a lot of kind of trying to do beat people, knock people. There have been very threatening comments made about people, my age, minors, and adults and teachers. I think that all of that is really exacerbated by social media because those threats can be made, but it’s easier to make them from a computer than at the board meetings. They’ve really taken advantage of that.

Do you think there are different implications for book bans in the South versus the North?

SP: When you have what’s going on in Florida, it means you’re going to water down what’s tested. You’re going to water down what’s educated in the classroom. You’re going to water down what’s presented in textbooks across the entire country (because national publishers often cater to the biggest markets). Just because one governor can have policies where he’s trying to turn the narrative around and say, like many Republicans believe today, that the biggest problem white Republicans face today is racism against white Republicans.

EF: Beaufort especially is very historically rich, the South is historically rich. I think that it is more important in the sense that so many of the effects of slavery are prevalent in the South, because, slavery was in the South.

Students are more drawn to fiction and young-adult books that reflect them. If we take those away, then we’re erasing our history. We’re kind of entirely cutting off any ties students would be able to have with the history and to be able to understand the effects of racism in our community. And in the South, it is really important to understand that history and its current effects.

In the North, I think I’m still going to say it’s equally important because I do think that a lot of people have the misconception that there was just generally less racism in the North, and there wasn’t. Access to fiction, access to readable stories for young adult audiences are so important in both of those locations.

What would you consider success?

SP: What Elizabeth is saying, and I agree with her, is that there is a censorship movement that’s growing and alive in this country right now. And it will probably continue to grow through the next presidential election. And many of the people behind the censorship movement today are simply trying to destroy our public school system by diverting public money to religious and private schools. And that’s where the subterfuge and the deception comes in.

There are well-meaning parents out there who want to be involved in their kids’ education. That’s great. But I think some of them are being fooled because part of the goal of a lot of book banners is to actually destroy and defund our public school system and divert the (public) money to private and religious schools.

EF: I asked myself that all the time in trying to figure out what are we ultimately fighting for? Part of why I think it’s difficult to answer is that all of this movement, kind of, right now is in response to this movement by the GOP, by Moms for Liberty, to dismantle the public school system and privatize education. And so at this point, my ultimate goal is to nip that in the bud.

My ultimate goal is that everybody in this country is able to exercise their constitutional rights freely. I think the ultimate goal is that we reinstate that as the default. I think that the these conversations will continue in different areas. I don’t think that the book ban movement is necessarily near its end, though. I think that the same arguments, the same efforts to destroy public education, will just present themselves in different ways.