89 historic Fort Leavenworth homes recommended for demolition. ‘Just breaks my heart’

In U.S. Army terms, rows of once spectacular homes that have graced historic Fort Leavenworth for more than 100 years stand in defeat.

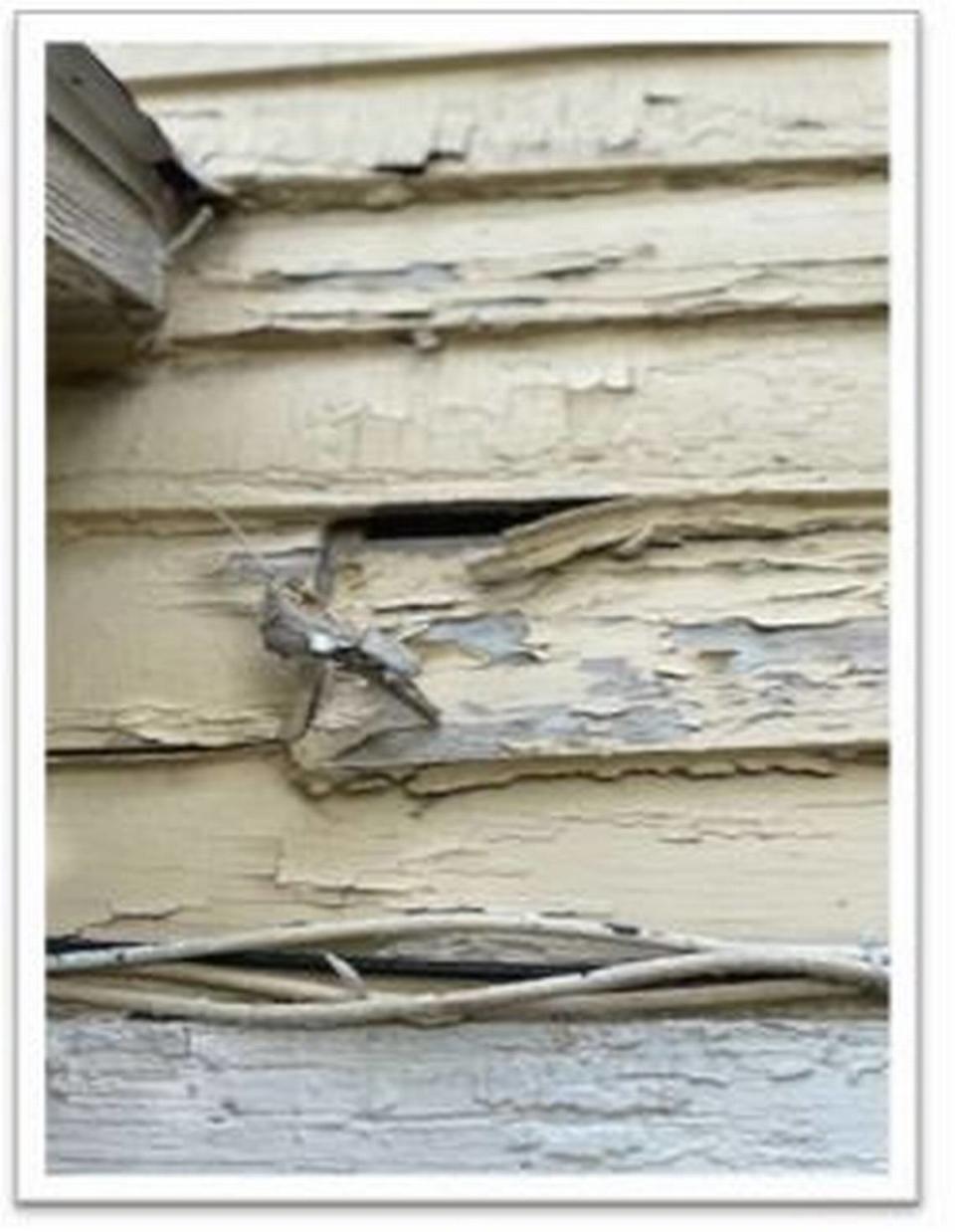

Like downtrodden troops, grand houses of red brick or yellow clapboard, many dating to the 1800s, have been left scarred, pocked and disheveled. The paint is flaked or falling in strips. Plaster and foundations are crumbling. Wood is rotting away. Pipes are corroding.

For almost two centuries, since it was established in 1827, the storied Army post set high above the Missouri River has distinguished itself.

The oldest U.S. Army garrison still in operation west of the Mississippi River, the fort is a National Historic Landmark with 269 houses and living quarters built before 1919 — more than any other Army garrison in the United States. That’s triple the number at West Point, more than double the 109 at Fort Riley (second behind Leavenworth) and fully 30% of the Army’s inventory of 865 spread across the country.

Some of Fort Leavenworth’s most beautiful historic homes are put on tour each year in the fall and spring.

But now, should a management company’s preferred “alternative” gain traction, 89 of the fort’s historic dwellings would fall to the wrecking ball and be rebuilt anew.

The recommendations were put forth by The Michaels Organization, the for-profit company with a 50-year lease to manage all of Fort Leavenworth’s housing.

In some cases, entire blocks would be destroyed. To military families on post who love its architecture, the mere suggestion of tearing down any of the historic homes has sparked outrage.

“The concern is that Kansas is going to lose its history. It’s easier for Michaels to tear them down and then just put up a cracker box than it will be to try to maintain a historic home,” said a Fort resident who lives in a historic home.

Like other garrison residents who spoke to The Star, the individual requested anonymity, fearful that their criticism could get them evicted, having signed leases with Michaels’ subsidiary — Fort Leavenworth Frontier Heritage Communities — stipulating they could be removed at short notice for nearly any reason.

The accusation against Michaels is that instead of doing what’s necessary to maintain the historic homes, the company is engaging in what often is known as “demolition by neglect,” allowing homes to deteriorate, hastening eventual destruction.

Documents suggest, however, renovation of the historic buildings could cost tens of millions of dollars.

“These houses are so strong. They’re so sturdy. They’re so solid. And they’re gorgeous inside,” said another resident, extolling the homes for their tin ceilings, moldings and curved staircases. “This history is going to be gone — wiped out.”

No definitive plan

The Army, however, is adamant. No concrete plan exists.

Yes, Fort Leavenworth leadership acknowledged to The Star in a statement, that in early 2023, the management company “as part of its due diligence … shared with Fort Leavenworth potential homes that might be considered for replacement as one of a variety of potential strategies as part of a future outyear development plan.”

That means long-term.

Based on what the company provided, the fort’s Directorate of Public Works put together a “conceptual” map in June of homes that might be demolished, said Scott Gibson, the fort’s public affairs officer.

The map included grand homes on leafy avenues like Riverside, Thomas and McClellan, as well as on Meade and Auger in the shadow of the clock tower.

“It should be noted that this discussion was pre-decisional,” Gibson wrote of the housing company, “and no proposal to replace the historical (pre-1919) housing has been officially submitted to the Kansas Historical Society for review.”

Any proposal to remove homes would need to show cost savings and would, by law, be required to be vetted by the Kansas Historical Society and other stakeholders, including the public.

The Michaels Organization indicated much the same, declining multiple requests by The Star to discuss the management or future of pre-1919 housing, their financial upkeep, or claims that it is engaging in “demolition by neglect.”

“We do not think this is the appropriate time to do an interview because there is no definitive plan in place to discuss,” Michaels’ spokeswoman Laura Zaner wrote in an email. “The bottom line is that we are actively working with all stakeholders to come to a final plan that allocates significant funding for the historic homes, but we think we are still about six months out from being able to share such a plan with you.”

Although no demolition plan currently exists, information verified by The Star shows that Michaels — through its Frontier Heritage management company — floated to the Army several alternatives to meet what it described as the unsustainable financial challenge of maintaining so much historic housing. The homes are burdened by problems that include outdated and faulty plumbing, heating and electric systems, along with asbestos and lead paint.

Moreover, because Fort Leavenworth is on the National Register of Historic Places, with homes in a National Historic Landmark District, if the company looks to restore, preserve, rehabilitate or reconstruct parts of the historic homes — from windows to spindles — it is required to adhere to strict federal guidelines known as the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties.

Doing so drives up costs, often requiring the use of original materials instead of modern replacements, along with specialized artisans.

Michaels listed pros and cons of the alternatives which ranged from taking no action on the historic homes beyond fundamental repairs and maintenance to the complete historic restoration of all 269 housing units, which include single-family and multi-family homes.

The option Michaels preferred was the restoration of 180 units coupled with the demolition of 89 others to be replaced by modern housing.

Residents, however, insist that if Michaels would fulfill its “program agreement” to maintain the housing in proper historic fashion — as it agreed to do in 2006 when it signed a 50-year contract to manage the post’s 1,700 living units — none of the historic homes would be imperiled.

Of the 269, Fort Leavenworth reports that 25% currently sit unoccupied. Whereas in 2017, one unit was pulled “off-line” — deemed unrentable because of its need for costly repair — that number is now 14.

“Why are they taking houses off the market? Why are they allowing houses to have leaks in the roof, and just rot and get black mold?” a resident asked rhetorically. “It’s a money deal. It cost too much to bring them up to standard. They can say, ‘Well, it’s so far gone, now we can demolish it.’”

Rooking The Rookery?

Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act requires federal agencies to inform state preservation officers, such as the Kansas State Historical Society, and the federal Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, about actions affecting historic properties.

Through a Kansas Open Records Act, The Star found that, over the last year, Fort Leavenworth’s Directorate of Public Works has reported a growing number of “adverse effects” from deferred maintenance by Michaels.

A report from September includes The Rookery, one of Kansas’ most historic buildings — a soldiers quarters built around 1830 and considered the oldest, continuously inhabited residence in the state.

The report is unsparing:

“The level of care and maintenance that this home has received,” it reads, “… is the living definition of ‘Demolition by Neglect.’ It is an unacceptable state of maintenance not only for the National and State legacy that is the Rookery !… but also for the level of quality of housing that the active military families of the United States ARMY deserve to live in.”

The Rookery file contains 50 photos of rotted wood, peeling paint, missing boards, cracked support columns, rusting and leaking gutters and an itemized list of “some” of what’s wrong:

▪ “Woodwork including fascia, trim, crown molding, window trim, rim joists, columns, porch decking, handrails and spindles that have been allowed to rot to the point of deterioration.” Other woodwork “has been repaired but not primed or painted properly.”

▪ “Support columns that are cracking, have inappropriate repairs, and are generally deteriorating.”

▪ “Windows that have deteriorating trim, weather stripping, framing, and asbestos containing glazing.”

‘Breaks my heart’

Another “adverse effect” from July contains an email about a three-story, Colonial Revival home built in 1905:

“Colonel,” it begins, “The British Liaison officer came to our office 7/25/2023 expressing concern about his porches and the repair and the safety of them especially for their child. He could not get a clear answer from Frontier Heritage.”

The report said new, unpainted boards had been laid atop rotted boards. Gutters were clogged causing water to run down the side of the house. Steps, handrails and a post were rotting through their decking.

“This has been an ongoing issue with the last resident, and before the last resident,” the letter read. Some partial repairs had been made, but their effectiveness was “questionable,” it said.

In another case, an adverse effects report complained that Michaels replaced a wood floor in one of the historic homes with an improper vinyl floor, asking for it to be removed and replaced. Outdoor wood repairs lack priming and painting.

A report from July on the Syracuse House, a grand two-story yellow duplex built in 1855, included multiple photos of rotted planking, trim, soffit, facia, railings and steps with unpainted patchwork repairs.

Documents on yet another 1905 home reads, “Basement ceiling has lost a good portion of its plaster coating. Lathe is exposed resulting in Fire Code violations. … Support structure for back porch is being deteriorated by insect infestation.”

The Army knows that its historic housing has been a decades-long issue, not only at Fort Leavenworth, but also on its posts across the country. In an October document titled “Program Comment Plan for Preservation of Pre-1919 Historic Housing,” Army Federal Preservation Officer David Guldenzopf called the Army’s pre-1919 housing “a significant concern.”

He wrote in that, in the long term, the obligation to meet the standards set by the secretary of the interior — to use historic or “in-kind” building materials and specialized artisans — is financially “unsustainable.” It estimated that continuing to do so could collectively cost $1.7 billion extra for Micheals and the other private companies that run the Army’s housing.

Guldenzopf, in the document, raised the possibility of amending program agreements so that the companies could use “imitative substitute building materials” rather than historic. The suggestion is already getting pushback from state historic preservation officers and from The National Trust for Historic Preservation who want more time to consider the change.

It was precisely because of the high cost of renovation that Congress last year, as part of the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act, mandated the demolition of three pre-1919 living quarters at Fort McNair in Washington, D.C., once they are empty for a year.

Opponents of demolition, both on and off the post, said it’s the last thing they want to see at Fort Leavenworth.

“You can see the neglect,” said a former resident, a self-described “Army brat” who lived in one of the historic homes as a child and still resides in Leavenworth. “It just breaks my heart.”