9/11 brought a sense of national unity. Why has the pandemic been marred by division?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Bad times bring out the best in people."

It must be true. Otherwise, it wouldn't be a cliché.

On the other hand, maybe clichés, like doctors, should be re-certified every once in a while. Does flattery really get you nowhere? Have good things ever come to those who wait?

Do bad times really make us better people? The 20th anniversary of 9/11 – occurring in the 18th month of the COVID-19 pandemic – offers a reality check. Also, a sobering study in contrasts.

Because if 9/11 brought us together, COVID seems to be tearing us apart.

"With COVID, there was a moment, early on, of greater unity," said Dan Cassino, professor of Government and Politics at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Madison, New Jersey. "[But] it passed pretty quickly,"

Looking back

We all remember 9/11. Or think we remember it.

That sense of national unity. The shared compassion for the victims and their families. The shared outrage at their attackers. The lionization of firefighters, emergency service workers, and others who risked their lives, sometimes gave them, to save their fellow citizens. The plaudits for the soldiers, heading off to war in Afghanistan, who are now – incredibly – just coming home.

Contrast that with COVID.

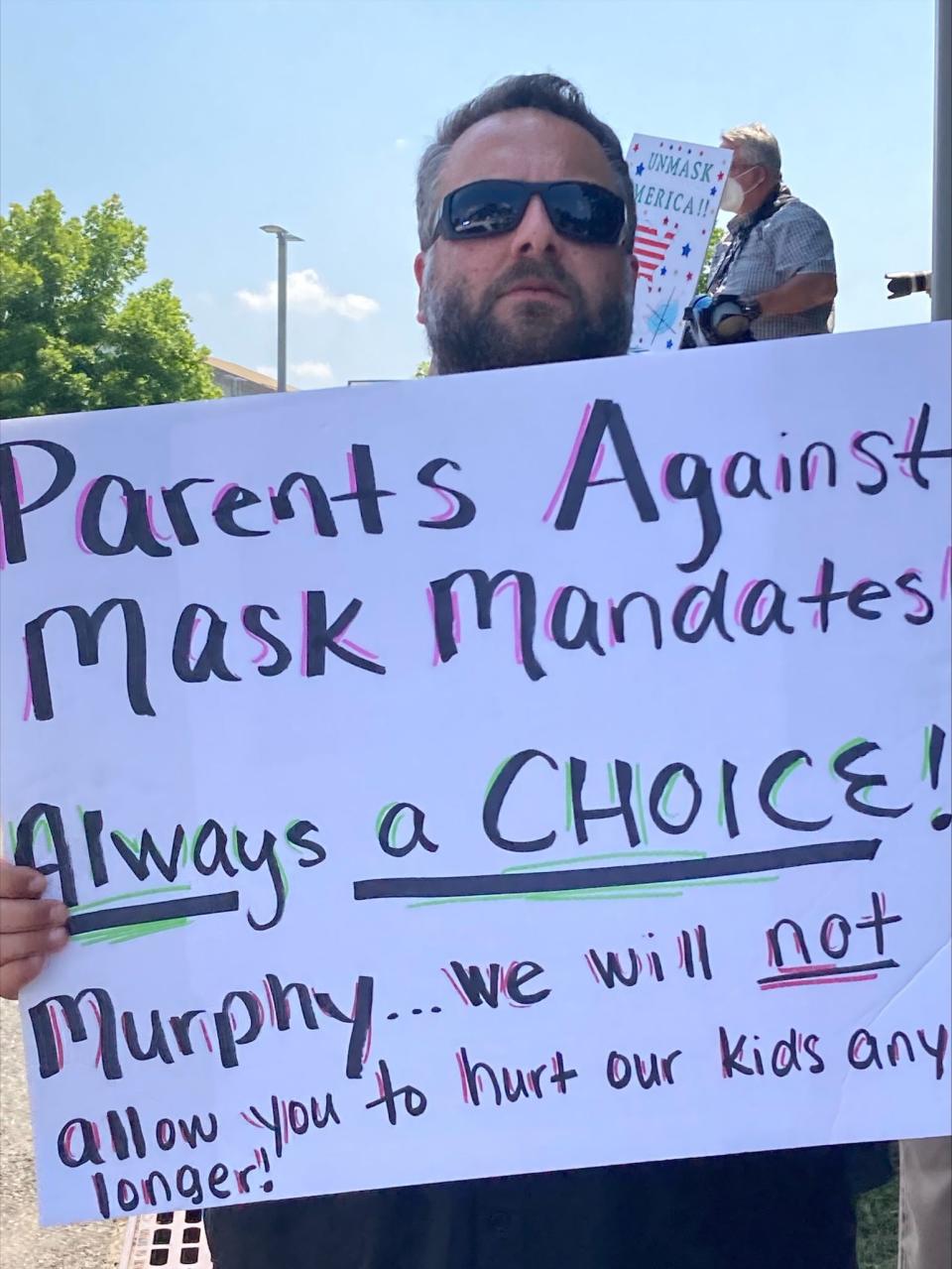

The meanness. The divisiveness. The name-calling, on both sides. The very fact that we have sides, in a national emergency that, in one sense, dwarfs 9/11. A total of 2,977 people were killed in the twin towers, the Pentagon and in the plane crash outside Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Some 621,000 Americans have died from COVID so far – and it isn't over.

20 years later: How a vision for the 9/11 Memorial blossomed into a piece of New York's everyday fabric

"Division has become a fashionable thing now – to be divisive and berate people," said Frank Messina, the Norwood, New Jersey-born poet who became a sort of bard of 9/11 with his 2002 book of poems, "Disorderly Conduct," which came out of his work assisting rescue workers at Liberty State Park.

He certainly remembers when the country came together, in the months after September 11, 2001. That's what his poems were about.

"Why would I want to knock anybody else down?" he said. "My intention is to lift people up. My poetry is not about opposing. It's about proposing."

His attitude seemed to be the common one, then.

Volunteers from the South and Midwest rushed in to search the rubble at Ground Zero. People from all parts of the country gave blood. Schoolchildren in reddest Texas wrote letters to kids in bluest New York.

People seemed to see the best in each other. Liberals conceded that Rudolph Giuliani had struck a sublimely tragic note when he said "The number of casualties will be more than any of us can bear, ultimately." Conservatives, meanwhile, admitted that Father Mychal Judge, a gay man, was undoubtedly a good man when he rushed to the towers to be with the firefighters and died praying for them.

Back then, Messina wrote a poem:

"love is strength in numbers,

your will is bound by hatred

America slumbers no more,

the giant has awakened"

If America was a giant then, today it more resembles a nation of squabbling Lilliputians. What happened?

Mitch Albom: As death tightens around us, don't hesitate to tell loved one how you feel

A common enemy

"I think the quick answer is that it's apples and oranges, and that it's really difficult to compare national emergencies," said Aaron R.S. Lorenz, dean of the School of Social Science and Human Services at Ramapo College in Mahwah, New Jersey.

It's best not to oversimplify, for a start.

Discord didn't just vanish on 9/11. If you were Muslim – or looked like you might be – you were not included in America's big group hug.

"Those moments of national unity aren't necessarily a good thing," Cassino said. "Think of the spike in anti-Arab American hate crimes after 9/11."

COVID, conversely, hasn't all been bickering and finger-pointing. The crowds who applauded medical workers, the volunteers who made masks, are proof that not all the better angels of our nature have flown south.

But America's mood, now, does seem very different from what it was 20 years ago.

"When something like 9/11 or Pearl Harbor, or even the Persian Gulf War happens, our identity as 'Americans' becomes more important because of what's going on around us," Cassino said.

Even back in 2001, we were a tetchy, testy, fractious nation – inclined to think in terms of identity in its narrowest sense. "Gay," Black," "Christian," "Southern," "Feminist" seemed real, to many of us, in a way that "American" did not.

Then the towers fell. A wall of smoke barreled down lower Broadway. People were seen – it's still incredible to think back on – plunging to their deaths from the 90th floor.

All of that was brought about by an enemy who saw us all as Americans, and nothing else.

"Those other identities that might divide us – like political party, or race, or religion – just don't matter as much in comparison," Cassino said. "So we become more united as a country. That doesn't heal those rifts in our society. It just papers over them, for as long as we're thinking about ourselves mostly in terms of that national identity."

9/11 gave us a foe. We had been attacked, by a foreign adversary. It was us versus them. And there was broad, general agreement on who "they" were.

But who is to blame for the current emergency? A virus?

Yes, as a matter of fact – but a virus is not a very satisfying bad guy. "9/11 gave us an external enemy," Messina said.

Perhaps it was really hate, more than love, that brought us together after 9/11. But at any rate, we could all agree on the culprit.

With COVID – depending on your political camp – the enemy is the last president. Or the current president. Or the people who won't take vaccines. Or the people who insist we all take vaccines. Or that woman not wearing a mask. Or the woman who yells at that woman.

Which viewpoints are reality-based? Which are nonsense? It's obvious – to whoever is doing the talking.

"The fact that the response to the virus became so politicized, so quickly, meant that responses became shaped by partisanship, gender and other dividing lines, making those more visible, and more important," Cassino said.

Paranoia is a symptom common to all pandemics. Any one of us could be the enemy. Any one of us could be a potential carrier. In science-fiction terms, 9/11 was "War of the Worlds." COVID is "The Thing." It can take the shape of your neighbor, or the guy in the convenience store.

"The potential enemy could be anywhere," Messina said. "Who is this woman in the elevator opposite me? The unwitting soldiers of this unseen enemy could be our own loved ones. Potentially it could be your own mother or brother or father or sister."

Did 9/11 permanently change life in the US? More Americans think so more than ever before

Divided we fall

But the nature of the threat isn't the only thing that's different, this time. So is the country.

In 2001, Facebook, Twitter, Parler didn't exist. The very terms "red" and "blue," in the political sense, were only a year old. Social media was still a seedling. Now it's grown high as an elephant's eye.

"I think the biggest issue with social media is that it has destroyed expertise," Lorenz said. "These are really complex topics. Infectious diseases, military actions in the Middle East – people study their entire lives about these things. Now they're summarized in catchy memes and quick posts."

Distrust of authority isn't new. But social media has put it on steroids. Back in the day, if you doubted your doctor, you might get a second opinion. Now, thanks to the internet, we can all get second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth opinions. Eventually, we're bound to find one that we like.

Social media, Lorenz said, "has created a false sense of equivalency to various experts in numerous fields."

And it's not only social media that has eroded people's trust in authority over the last 20 years. It's authority itself.

Remember "weapons of mass destruction"? Remember Colin Powell at the U.N. in 2003? "We listened to experts, and they lied," Lorenz said. "There's an anti-intellectualism that results from this."

Is it so surprising that some people might not be willing to blindly trust the government now? Even if Dr. Anthony Fauci is speaking from 50 years' experience in immunology, and likely knows what he's talking about? He's still speaking for the government.

Back in 2001 there was faith – or at any rate more faith – in institutions, Lorenz said.

"There was a Gallup poll in December of 2000, when Bush v. Gore was making its way through the courts," he said. "Essentially the question they asked is, if this case makes its way to the Supreme Court, do you trust the court to render an outcome you find acceptable?"

By a two to one margin, Gallup found, the Supreme Court's decision had not caused Americans to lose faith in the judiciary. They also said that the Supreme Court was the best institution to resolve the dispute.

Today – after several years of controversial Supreme Court appointments – would the public be as trusting? And if the Democrats were to "pack" the court, as some have proposed, would they be any more so?

"What might we see now, if a poll was done about the U.S. Supreme Court resolving mask mandates and vaccinations?" Lorenz said.

So a lot has changed, in the 20 years between 9/11 and COVID-19. To what end? Will sanity, empathy, solidarity prevail at last? Lorenz likes to thinks so. He has to think so.

"I believe facts win out," he said. "I'm a trusting person."

'Trying to catch every case': Are cheap home COVID-19 tests the delta antidote?

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: 9/11, COVID pandemic illustrate two very different US responses