How 9/11 changed the Republican Party

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

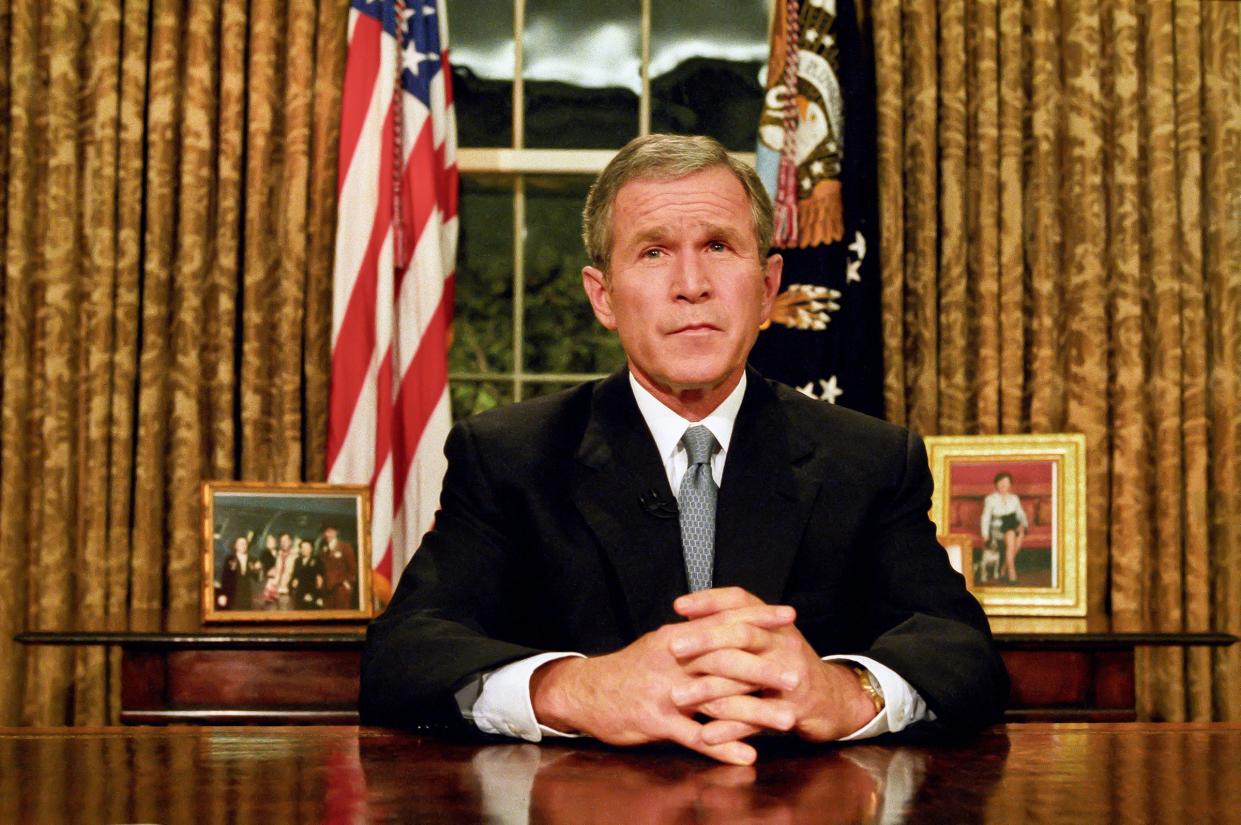

In the summer of 2001, US president George W Bush’s administration considered allowing more than 3 million undocumented immigrants from Latin American countries to secure legal status in the United States.

But when terrorists attacked the United States at the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon, and had their plot thwarted in Pennsylvania, it changed the trajectory of how the Bush administration and the Republican Party would approach immigration. In the 20 years following 9/11, the Republican Party’s response would change the makeup of its party coalition, and subsequent events would fundamentally alter the party into becoming more nativist and exclusionary towards immigrants, all culminating in the current iteration of the GOP.

Julian Zelizer, a professor of history at Princeton University, says that 9/11 in some ways proved politically beneficial for Republicans, as it led to increasing electoral success for the GOP and solidified their majorities in Congress. In 2002, Republicans broke the traditional trend of the party in power losing seats when it gained seats in both the house and the Senate. It did so largely by portraying Democrats as being soft on national security. Perhaps most infamously, in Georgia, Saxby Chambliss beat Sen Max Cleland, who had lost both his legs and his right forearm serving in Vietnam, largely on the back of an ad that opened with Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein.

The election also marked the final chapter of the Republicans’ takeover in southern states, which had begun in the 1960s and accelerated in earnest in the 1980s, as they won over the remaining white formerly Democratic voters, defeating incumbent Democrats in states like South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama. Democrats have since failed to win governorships in any of these states.

“The sorting of the parties, which was under way in 2001, is now complete,” says John Pitney, a professor at Claremont McKenna College. Mr Pitney adds that the party has become far more conservative: “There are no liberals in the Republican Party.” But after Mr Bush’s re-election in 2004, American dissatisfaction with the war in Iraq would lead to Barack Obama’s election. Mr Obama, who was a Democrat, frequently criticised the war, saying the United States “took our eye off the ball”. Mr Obama would also later order the operation that killed Bin Laden.

In turn, Donald Trump’s campaign in 2015 vocally criticised the war in Iraq and frequently used it as a point to knock Mr Bush’s brother Jeb Bush, who was his opponent for the GOP nomination. “Politicians learn right away that they can openly question what was hereto seen as Republican doctrine,” says Suhail Khan, who served in the Bush administration. “And not only that, but they can succeed And there was an appetite to reassess and withdraw with some degree from these military forays.”

Similarly, Mr Zelizer notes that the GOP response to 9/11 bred an appetite for the nativism within the Republican Party that would animate its members.

While Mr Bush supported immigration reform, his administration also created the Department of Homeland Security, and would face a revolt from the party in trying to find a path to legalisation for undocumented workers. In 2007, his proposed legislation, which would have offered legal status to undocumented immigrants, died in the Senate, with all but 12 Republicans voting against it. Sen Jeff Sessions of Alabama was one of the leading voices against the legislation, and when it failed he told The New York Times that supporters wanted to pass the bill “before Rush Limbaugh could tell the American people what was in it”.

Eventually, Donald Trump’s administration would use the Department of Homeland Security and the Justice Department, now led by Mr Sessions, to implement some of his most draconian measures on the US-Mexico border, such as the so-called “zero-tolerance” policies and the separation of families.

Similarly, while Mr Trump at least rhetorically rejected the concepts of the war on terror, such as nation-building in Iraq and Afghanistan, he capitalised on the growing nativism within the party. In the days following the terrorist attacks, Mr Bush was quick to say that the United States was not at war with Islam, a claim repeated by Mr Obama after the Bin Laden raid. But during that time, Mr Trump, then a reality television star, hinted that Mr Obama’s birth certificate might reveal that the president himself was a Muslim.

Mr Trump would go further when he ran for president in 2015, calling for a ban on Muslims entering the United States and saying he thought Islam hated the United States. But he could not have found much cache if there hadn’t already been fomenting anti-Muslim sentiment within the GOP. In the months after 9/11, the Pew Research Centre found that Republicans were only slightly more likely than Democrats to say that Islam encourages violence more than other religions. But that proportion would mushroom over the years.

When Mr Trump became president, he implemented a travel ban from countries with large Muslim populations, and repeatedly attacked Muslim members of Congress.

But while the GOP was almost entirely unified on how to confront the terrorist attacks on 9/11, it has been left split in the wake of the 6 January would-be insurrection. On that day, Rudy Giuliani, who after 9/11 was hailed as “America’s mayor” by the media, addressed a crowd of Trump supporters in support of what he called “trial by combat”, shortly before they raided the Capitol in an attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election. Meanwhile, Rep Liz Cheney – the daughter of Dick Cheney, who was vice-president in 2001 – voted to impeach Mr Trump for inciting the insurrection. Mr Giuliani is still widely welcomed within the party; Ms Cheney has been all but exiled.

Read More

White House, business groups tangle over Biden tax increases

Biden's vaccine rules ignite instant, hot GOP opposition

Justice Stephen Breyer calls Texas abortion law ‘very, very, very wrong’

California's Newsom votes as recall against him nears end

Gov vetoes North Carolina bill limiting K-12 racial teaching