90 years later: Michigan’s role in starting and ending Prohibition

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (WOOD) — Your New Year’s celebrations might look a lot different if it weren’t for the 21st Amendment. This December marks 90 years since the constitutional amendment was ratified, ending Prohibition — the country’s ban on alcohol.

In Michigan, it was a New Year’s Eve celebration that marked the end of it all.

After a “dry decade,” many Michiganders were fed up with Prohibition and pushed to legalize alcohol once again. It forced lawmakers at the federal and state levels to work together and work quickly to implement a regulation system.

It all eventually led to Dec. 5, 1933, when Utah became the 36th state to ratify the 21st Amendment and officially end Prohibition and Dec. 30, 1933, when Michigan’s first liquor stores opened for business.

BANNING BOOZE

The Prohibition Era technically spans 1920 through 1933 but its roots go back decades. The push to ban alcohol stems from the Temperance movement, Christian organizations that urged people to abstain or at least moderate their drinking. The first groups popped up in New York in the early 1800s and had swept across much of the United States by the 1830s. That influence crept into governments at virtually every level, eventually building up enough supporters to pass legislation in many counties and states to ban alcohol.

Hundreds of people march down Manhattan calling for an end to prohibition. (AP file) People enjoy legal drinking at a New York City restaurant on Dec. 5, 1933, hours after the 21st Amendment was ratified, ending prohibition. (AP file) People prepare to enjoy legal drinking as they gather on Dec. 5, 1933, in New York City, hours after the 21st Amendment was ratified. (AP file) Two employees prep beer barrels to be tapped after low-alcohol beer was legalized in March of 1933. (AP file) A salesman at Bloomingdale’s department store in New York sells the store’s first bottle of legal liquor following the repeal of prohibition on Dec. 5, 1933. (AP file) Photo) Dorothy Wentworth, right, and a friend share a legal cocktail on Dec. 5, 1933, at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City. (AP file)

Evangelist Billy Sunday was one of the movement’s leaders, preaching that the country’s “social ills” would be fixed by simply banning alcohol. He famously said in a recorded speech, “I will fight the saloon from Hawaii to Hoboken.” Plenty of people believed him and his claims that cities could close their jails and use them as corn cribs if alcohol was banned.

Personal papers from President Woodrow Wilson show how the conversations shifted in the White House, documenting letters and telegrams that he received arguing for and against Prohibition.

“There is a great difference between temperance and hysterical prohibition,” one letter said. “Doctors from all over Boston and greater Boston are prescribing liquors of all kinds to head off the terrible Influenza epidemic.”

Stanley Ketchel: How ‘The Michigan Assassin’ found himself on the wrong end of a rifle

Wilson vetoed Congress’ bill for Prohibition, writing, “In all matters having to do with the personal habits and customs of large numbers of our people, we must be certain that the established processes of legal change are followed. In no other way can the salutary object sought to be accomplished by great reforms of this character be made satisfactory and permanent.”

The House and Senate disagreed and responded with enough votes to override the veto and pass the bill into law.

The process moved even faster in Michigan. According to Michigan’s Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs, which now oversees the state’s Liquor Control Commission, most of the state was “dry” by 1911, with several counties enacting their own alcohol bans. In 1916, voters approved a statewide ban that would ban the “manufacture, sale, keeping for sale, giving away, bartering or furnishing of alcohol.”

Michigan’s ban took effect in May of 1918, months before Congress ratified the 18th Amendment on Jan. 16, 1919, and nearly two years before Prohibition officially became the law of the land on Jan. 17, 1920.

ON SECOND THOUGHT…

President Herbert Hoover, who held the office from 1929 to January of 1933, called Prohibition a “noble experiment,” but historians say it immediately became clear that legal bans on alcohol only generated more problems.

Prohibition gave rise to several illegal industries. Instead of simply deterring people from drinking or providing some form of regulation or oversight, it drove everything underground. Smuggling, bootlegging and speakeasies became a major source of income and were quickly monopolized by organized crime families.

Before things got better, they got worse. While the 18th Amendment did not prohibit possession or consumption of alcohol, states were allowed to enact tougher laws. The Michigan Legislature beefed up its efforts in 1927, making any liquor violation a felony offense. A Lansing woman soon became the face of the new law and became a turning point for the argument about alcohol.

Pigeon Hill: Another piece of West Michigan lost to time

One year after that new law, Etta Mae Miller, a 48-year-old mother of 10 was arrested for allegedly selling two pints of homemade moonshine. The charges were her fourth offense, meaning she was automatically sentenced to life in prison.

Miller’s case made headlines across the country and pushed the debate forward, with the negative aspects of Prohibition now seemingly outweighing the positives. Her sentence was eventually commuted by Gov. Fred Green in 1930.

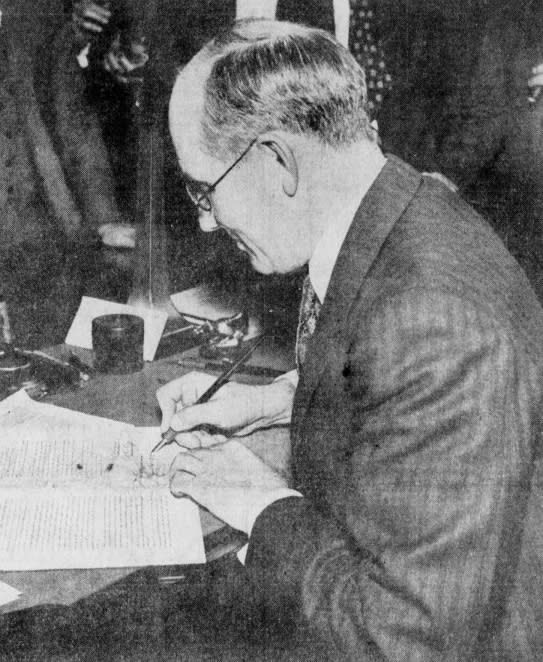

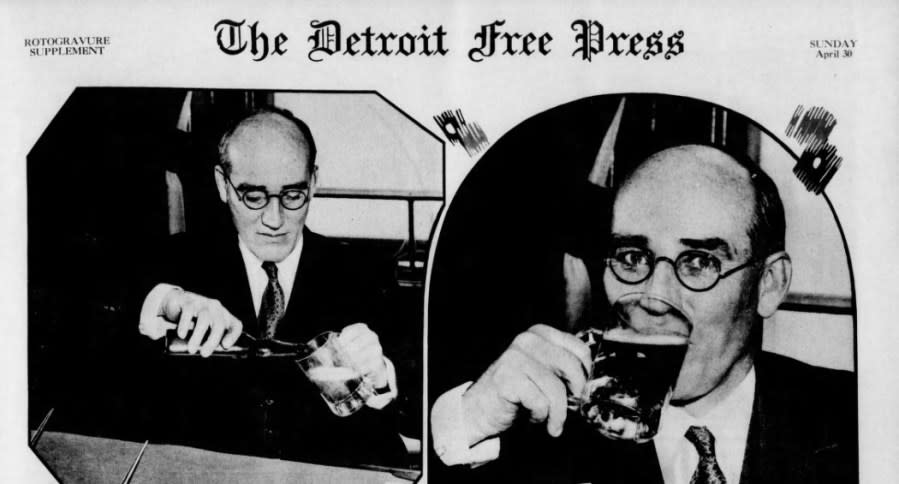

In this April 27, 1933 file photo, Michigan Gov. William Comstock signs the Public Act 64 of 1933, which legalized the sale of low-alcohol beer and wine in Michigan and created the Michigan Liquor Control Commission. (Courtesy LARA/The Detroit Free Press) A special edition of The Detroit Free Press includes photos of Michigan Gov. William Comstock pouring and sipping a beer on April 30, 1933. Before prohibition was repealed, beer with low levels of alcohol were approved for sale. (Courtesy LARA/The Detroit Free Press)

By 1932, the debate had passed its tipping point. The “noble experiment” had failed. There were thousands of speakeasies and “blind pigs” across Michigan alone, and spikes in violent crime could be traced directly to Prohibition. According to historian Christopher Klein, an estimated $300 million was spent by the federal government enforcing Prohibition laws and an estimated $11 billion in tax revenue was lost by banning alcohol instead of regulating it.

It was apparent that the ban could not be realistically enforced. In November of that year, voters returned to the polls to repeal the amendment to the Michigan Constitution they had passed years earlier and establish a control commission to regulate alcohol if a federal ban was ever lifted.

PBB: How a simple shipping error poisoned most of Michigan

It was a sign of things to come. In March 1933, Congress passed the Cullen-Harrison Act, which amended federal law to legalize the sale of beer and wine as long as the alcohol content was below 3.2%. And in April, when the formal process for repealing Prohibition first started, representatives from Michigan — one of the first states to adopt Prohibition — became the first state to repeal it by ratifying the 21st Amendment.

No amendment is officially adopted until it is approved by three-fourths of the states in the union. Many states rushed to put together conventions and ratify the amendment. On Dec. 5, 1933, Ohio and Pennsylvania became No. 34 and No. 35, and at 3:32 p.m. local time, Utah became state No. 36, enshrining the 21st Amendment into the U.S. Constitution.

People and businesses in 18 states were ready. Shortly after Utah’s announcement, Under Secretary of State William Phillips signed the final documents and liquor started flowing legally there.

“Delivery Truck engines purred as they left liquor warehouses. Thousands of champagne corks popped, and hundreds of thousands of glasses clinked to toast drinkers’ regained freedom,” Klein wrote. “By late night, licensed establishments were packed as jazz bands played and drinkers rightfully sang ‘Happy Days Are Here Again.’”

The happy days were still a few weeks away for Michigan. Despite the November 1932 vote, the state still had laws on the books that needed to be addressed. The Legislature was able to act quickly, and the newly formed Liquor Control Commission got to work getting stores open and regulating how to allow liquor to be sold easily.

Seven liquor stores were ready to open by Dec. 30, when Michigan’s liquor laws took effect: three in Detroit and one each in Grand Rapids, Kalamazoo, Jackson and Saginaw. Many hotels and restaurants were also granted two-day licenses to allow them to purchase liquor from outside providers — with a 40% tax — to get stocked up for the New Year’s holiday.

Gov. William Comstock commemorated the new laws by purchasing the state’s first legal bottle of whiskey — Old Taylor Bourbon — from a store in Detroit.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to WOODTV.com.