Abandoned as a newborn in a Teaneck apartment building, a man seeks answers 77 years later

Tony La Spina was about a day old when he was found in the second-floor hallway of a Teaneck apartment building in August 1946, wrapped in a cloth napkin, polo shirt and blanket.

As far back as he can remember, La Spina, who is now approaching his 77th birthday, heard stories of how he was found, of the newspaper articles describing the search for his parents in the days that followed, and of how his adoptive mother saw the reports and sought him out.

Only in recent years has he begun to look in earnest for more information about his background: How did he come into this world, who were his parents, and why did they give him up?

La Spina doesn’t even know his birthday for sure. Doctors estimated it to be one day before he was discovered on the night of Aug. 13 by a tenant of the building.

“I wish I hadn’t waited so long,” he said. “It’s always been there. I’ve always wondered about my roots. Everyone wants to know where they came from. I was left in a laundry basket in the hallway of an apartment building. There has to be a story behind that.”

The day after La Spina was found in the hall at 35 Tryon Ave., a story ran in what was then known as the Bergen Evening Record with the headline: “Trace clues to abandoned boy; Teaneck follows leads in foundling case.”

The newborn weighed 8 pounds, 12 ounces, and was described as “in good health.” Mrs. John Pinkham found the child outside her door and called the police, who took him to Holy Name Hospital. Officers sent the infant’s clothes to New York Police Department laboratories to check for clues that might lead them to his parents.

Two weeks later, another story appeared: “Baby’s folks still being sought by hospital.”

“Officials there are hopeful that some information will come in, even by anonymous letter, regarding the child’s background,” the story read.

With no leads on the birth parents, La Spina became a ward of the state. The staff at Holy Name called him Richard O’Brien because they thought he “looked Irish,” La Spina said.

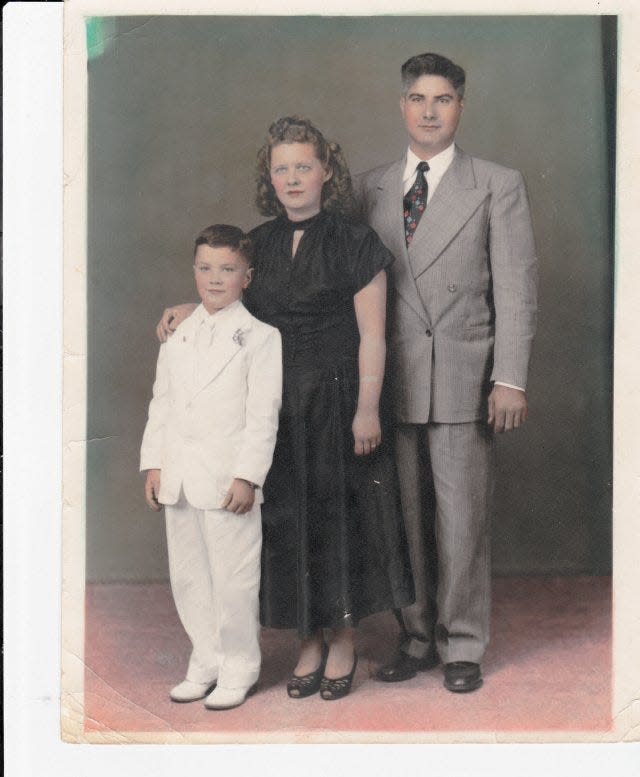

After reading the stories in the paper, La Spina’s adoptive parents, who lived in Park Ridge, immediately called to take him in.

They weren’t alone. According to newspaper accounts, the hospital received many letters, some from “out-of-state persons,” asking to adopt the infant. La Spina’s parents did eventually gain custody and legally adopted him at 20 months old in what was then called Bergen County Orphans’ Court.

Richard O’Brien remained his legal name until the adoption order was signed, when he was renamed Anthony Edward, after St. Anthony, to whom his mother prayed every night to bring her a child.

When La Spina’s mother, Helen, was a toddler, she pulled a hurricane lantern into her crib, setting a fire in the bed. She was burned badly, and because of her injuries she was unable to have children.

“She probably felt like her prayers were answered,” La Spina said. “My mother loved children endlessly.”

As a young child, before the family moved to Phoenix when he was 8, La Spina remembers visiting a social worker on Main Street in Hackensack from time to time. She would ask: Was he happy? Did he like his family?

“I told her I loved them,” he said.

His parents were always open about his past, but La Spina said he got the sense his mother would be hurt if he became too curious.

“My mom was very sensitive to that,” he said. “She would say, ‘Well, I may not have had you, but I’m your mother.’”

When he was around 10, a boy across the street teased him for being adopted. His mother told him: “His parents took what they got. Your mom and dad picked you.”

“I grew up with that belief,” he said. “I was chosen by them.”

When he was a teenager, La Spina’s parents adopted another baby, a sister. He served two tours in Vietnam, and after each one he came home to a new adopted sibling.

Soon after returning from Vietnam in 1972, he married and went on to have two children. The couple later divorced, and he married his wife Pam in 1979. After leaving the military, he worked alongside his father at a plant manufacturing aircraft engines.

More: How much does social media affect children? NJ creates commission to find answers

Through it all, he felt the pull to untangle the mystery surrounding his beginnings. He always loved the ocean; was his biological father a sailor returning home from the war? Did his biological mother feel ashamed of her circumstances when she left him in that apartment hall?

The death of La Spina’s father in 2015 led him to search for information about his past. His mother died years before, shortly after he remarried.

“With both parents gone now, sometimes it feels like I’m alone in the universe, except for my wife and children,” he said. “I’d just really like to know something while I’m still here.”

It’s not uncommon for older adoptees to search for answers later in life, said Ryan Hanlon, president of the National Council for Adoption.

More: Want some good news in your inbox for a change? Sign up for this good news newsletter

They may have health concerns and wonder about their family’s medical history or want to forge connections with biological relatives.

“Sometimes it can feel like an open question mark until you get those answers,” Hanlon said.

Adoption practices have changed dramatically since the 1940s, when records were often confidential or sealed.

Younger people often don’t need to seek answers. Adoptions are largely open, and many children have ongoing relationships with their birth parents.

La Spina’s search is complicated by the scarcity of records because of his abandonment, and the amount of time that has passed.

His birth parents would be around 100 or older. Most of the people who met him as an infant — the police officers, nurses, the woman who found him outside her apartment door — are likely no longer alive.

“I wish I had started this 40 years ago,” he said. “I don’t know who is out there who can tell me anything more.”

But each discovery brings renewed hope and more understanding of his roots, he said.

Until La Spina wrote to The Record asking if there were archived articles about his abandonment, he had never read the stories himself.

The brick building where La Spina was discovered as a baby still stands, just across from Bryant Elementary School near Teaneck Road. Seeing a picture of the building online made him wonder: Was this where he was born? Did his parents live nearby?

“I’m amazed just looking at it. I’ve just been trying to figure this all out,” he said.

Genetic testing is one of the few paths for adoptees like La Spina who have limited paper trails to follow to learn about their family trees. He has used anscestry.com and myheritage.com, which turned up some possible third and fourth cousins in the U.S. and in different countries.

He also learned he is mostly of Irish descent, confirming those hospital workers’ guesses all those years ago.

DNA testing databases are limited to the number of people who have used their service, so La Spina said he may try others as he continues to look for connections to blood relatives.

“Maybe I’ll get lucky and find some kind of family link,” he said. “I want to know more. I’m going to see where it leads me.”

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Abandoned as a newborn in Teaneck, a man seeks answers 77 years later