Abercrombie & Fitch was America's hottest brand. It became 'what discrimination looks like'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If you came of age sometime between the two Bush presidencies, chances are you’ve had — or still have — strong feelings about Abercrombie & Fitch, the retailer whose logo T-shirts were once ubiquitous in high-school cafeterias.

Perhaps you aspired to the brand’s narrow definition of cool. Perhaps you resented the company’s exclusionary identity. Perhaps both. But you simply couldn’t be a young person in the late 1990s and early 2000s and avoid Abercrombie.

Now, a new Netflix documentary examines the brand and its legacy, arguing that Abercrombie’s corporate culture was even more noxious than the cologne its employees dispensed with zeal at malls across the country.

Premiering Tuesday, “White Hot: The Rise and Fall of Abercrombie” explains how the company, founded in the 1800s as a purveyor of sporting goods for elite adventurers, became the hottest label of the "TRL" era under the leadership of Chief Executive Michael Jeffries, who made billions in profits by aggressively going after the cool kids — and who once proudly declared, “A lot of people don't belong [in our clothes], and they can't belong.”

The strategy worked for a time, but it was unsustainable: nothing that burns white hot can last forever. Especially when the brand is built on exclusion.

“This is a story that everyone can locate themselves in,” said director Alison Klayman. “People immediately start talking about their personal experiences with the brand. It cuts quickly into something about identity, about childhood, about fitting in.”

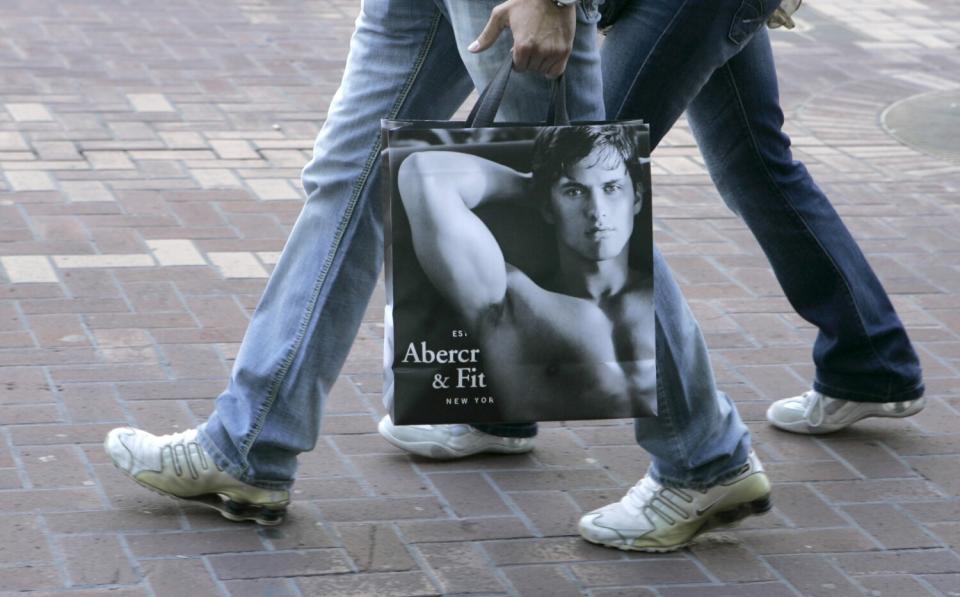

The film recounts the innovations that propelled the company’s ascendance in the ’90s, including A&F Quarterly, a racy catalog/magazine shot by famed fashion photographer Bruce Weber, and store employees who were hired because of their looks rather than their customer service skills. The Abercrombie vision flowed directly from Jeffries, who dictated every aspect of the company’s image, down to the jewelry and hairstyles worn by employees. (Dreadlocks and gold chains were forbidden.)

The company’s popularity was crystallized in the 1999 hit “Summer Girls” by the second-tier boy band LFO, which played in heavy rotation on MTV: “I like girls that wear Abercrombie & Fitch,” went the chorus.

But “White Hot" also traces the controversies that ultimately turned the tide of opinion against Abercrombie and contributed to Jeffries’ ouster in 2014, including racist merchandise, allegations of discriminatory hiring practices that resulted in a landmark Supreme Court case and allegedly predatory behavior by Weber toward the company’s young male models.

Klayman said she was drawn to make a film about Abercrombie because she thought it was “the perfect story to make seemingly abstract forces really concrete. It shows you how bias in society is actually formally enforced in a top-down way. How do you explain systemic racism? Well, how about people from corporate headquarters coming to your store and telling a 20-year-old who they should hire and fire?”

The filmmaker grew up in suburban Philadelphia during the retailer's heyday. She preferred thrift-store finds to Abercrombie’s casual preppy styles and felt intimidated by the store at the local King of Prussia Mall. “I wasn't skinny or blond, so I knew it wasn't for me,” she said. "I received the message that this is what was cool. And I also received the message that it wasn't for me.” (The documentary, while comprehensive, doesn’t have time to rehash all of Abercrombie’s controversial moves, like the thongs marketed to preteen girls with the words “eye candy” on them or the decision for many years not to make women's clothes larger than a size 10.)

"White Hot" is likely to conjure complicated emotions in the millennials who grew up under the Abercrombie influence — nostalgia for mall culture, the pre-social media era and the brands we yearned for as adolescents, tinged with disgust over the pervasive racism, misogyny and homophobia that seemed perfectly acceptable in the not-so-distant past. (Some viewers also will feel very old when malls are explained as “an online catalog that’s an actual place.”)

The documentary arrives at a moment when pop culture is caught in a Y2K time warp. Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez are engaged, Britney Spears is pregnant and low-rise jeans are back in style. TV has offered sympathetic portrayals of women once treated as media punching bags like Spears, Janet Jackson, Monica Lewinsky, Brittany Murphy and Pamela Anderson. “America’s Next Top Model,” a show that debuted nearly 20 years ago, has been the subject of journalistic exposés and countless outraged Twitter threads.

And the recent Hulu docuseries “The Curse of Von Dutch: A Brand to Die For” told the wild story behind another clothing company strongly identified with the early aughts. Much as yuppies endlessly relived the 1960s throughout the 1980s and 1990s, millennials and younger Gen X are looking back at their youth and wondering: Why did we ever put up with this?

“Pop culture was so much more hegemonic in that era — it was more of a monoculture. There were plenty of people who thought [Abercrombie] was ridiculous from the beginning, but it was the dominant culture and they weren’t going to drown that out,” said Klayman, who has spent several years thinking about this time period: Her previous film, “Jagged,” focused on 1990s pop star Alanis Morissette, and she’s also working on a documentary about the WNBA, which was founded in 1996.

“White Hot” features interviews with journalists who covered the retailer at the height of its influence, as well as former models and employees disillusioned by the company’s exclusionary policies. (A model named Bobby Blanski jokingly describes himself as “armpit guy” because of a famous ad featuring his likeness.)

As an undergraduate at Cal State Bakersfield 20 years ago, Carla Barrientos applied for a job at an Abercrombie store at the nearby Valley Plaza Mall. She loved the clothes, and was devoted to a pair of low-rise jeans with tiny pockets on the front. “I am not sure what they were supposed to hold,” said Barrientos, laughing during a recent video chat. “At the time, everything I wore was low-rise, everything was tight. If I could show my belly button, it was a great day.”

Though Barrientos, who is Black, noticed the lack of diversity at the store, she figured, “They’re looking for all-American, and I’m all-American.” She worked at Abercrombie for a few months but was soon phased out with little explanation. When she learned another friend, who was white, was still working 20 hours a week, she began to piece it together. But she didn’t immediately take action. “I looked at it like, racism has to be blatant — almost like the KKK, right? I wasn’t called a racial slur, I wasn’t run out of the store,” she said.

“I think part of me didn’t want it to be about race,” she continued, “because there's nothing I can do about that. I'm very proud of being a Black woman. How can I fix that?”

Barrientos, now 38, ultimately joined a class-action lawsuit against the retailer in 2003, alleging that the company’s hiring practices excluded people of color and women. The case resulted in a 2005 consent decree that required the company to promote diversity in its workforce but was largely nonbinding. After the settlement, Abercrombie found a cynical workaround: If it reclassified the employees who worked in the front of the store as “models,” it could continue to hire them based on looks. In a separate case a decade later, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of a young Muslim woman, Samantha Elauf, who was refused a job at Abercrombie because of her headscarf.

The experience at Abercrombie “opened my eyes to what discrimination looks like” and how quietly insidious it can be, said Barrientos, who appears in “White Hot.” She is heartened to see the changes at Abercrombie, whose website now features models with an array of body shapes and skin tones. A banner on the home page reads, “Today — and every day — we’re leading with purpose, championing inclusivity and creating a sense of belonging.”

“It's so refreshing and beautiful to see how inclusive the world is these days, and how people want to know you because you're not like them, not because you fit this box of what's cool,” Barrientos said. “I'm so glad that we are where we are, but I think you've still got a long way to go.”

Though she credits social media and the rise of a new generation "that wasn't willing to be spoon-fed" with accelerating Abercrombie's fall from its turn-of-the-millennium heights, Klayman also sees less inspiring forces at work: falling profits and changing consumer habits. "It's really hard to be on top of the youth market for many, many decades. Abercrombie had a formula that worked, but it didn't change."

In other words, the brand suffered the fate of every fad: The cool kids grew bored with it.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.