Abortion funds are in the spotlight with the end of Roe v. Wade – 3 findings about what they do

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As soon as the Supreme Court handed down its ruling that signaled the end of legal abortion in much of the country, calls for donations to abortion funds immediately rang out.

There are at least 90 of these funds – donor-funded nonprofits that are often staffed by volunteers that help people obtain abortions they can’t afford by reducing the cost and assisting with travel, lodging and other services.

Before the ruling on June 24, 2022, abortion was already inaccessible in many cases because of restrictive laws in such states as Texas and Mississippi that have left many counties with no abortion clinics at all. Abortion funds generally partner with providers to help cover some out-of-pocket procedural costs on behalf of the patient, and some funds cover associated expenses such as travel, child care and lodging for overnight stays.

As a social work professor who studies reproductive health care, I have led research that reviewed thousands of case records of patients who requested assistance from abortion funds to help pay for a procedure that they could not afford.

Here are three main findings from the studies I’ve conducted so far:

1. Those assisted are likely to be parents

About 20% of the people aided by these funds were 11-19 years old, according to studies I led based on national data collected from 2010-2015. In contrast, only 14% of all people getting abortions are in that age group.

As is the case for all patients who have abortions, more than half of the people getting help from the abortion funds we studied were in their 20s. Only 18% of them were in their 30s, versus 25% of all patients.

My team also found that only 60% of abortion fund patients were single, compared with 86% of all patients. And we determined that 50% of them were Black, versus 36% overall.

Nearly 60% of patients aided by abortion funds have children. Around 41% have one or two children, as opposed to 46% of all people who got abortions, and 18% of abortion fund patients had three or or more children, versus 14% overall.

These findings suggest that younger parents of color were disproportionately affected by abortion barriers during this period.

2. Not all costs covered

My research team found that abortion funds didn’t cover the full cost for patients, or even the entire gap between the cost and what they could afford.

Patients typically requested help to pay for a procedure they expected to cost over US,200, when patients could only pay an average of 5. Abortion funds, in turn, were able to pledge an average of 6 on behalf of each patient.

We also determined that abortion costs were highest for patients age 11-13, at just over an average of ,000. Those patients had only an average of 6 to pay those bills, and they received an average pledge of 4.

I also participated in another project that analyzed more detailed data collected from 2001 to 2015 from an abortion fund operating in Florida. These patients faced an average procedural cost of almost

In March 2021 Pope Francis became the first leader of the Roman Catholic Church to visit Iraq. The number of Christians in Iraq has fallen sharply in the past two decades amid mass violence at the hands of the Islamic State group. Iraq stands today in the region of the ancient Babylonian Empire, generally understood as the homeland of the patriarch Abraham, the foundational figure shared by Judaism, Christianity and Islam – commonly called the “Abrahamic” religions.

As the pope met with local Christian and Muslim leaders, the names of other, smaller religious groups found in Iraq also made the news. One of these was likely unfamiliar to the majority of those in the English-speaking world: the Mandaeans. Also called Sabians, they are followers of the last Gnostic religion to survive continuously from ancient times down to the present day.

Gnostic religions view the material world as the product of a mistake in the heavenly realm, the creation of one or more inferior divine beings rather than the supreme God. Gnosticism also emphasizes that human beings can become aware of this and prepare their souls to escape from under the influence of the malevolent spiritual forces that created and rule this realm, so that when they die they can ascend to the good realm that lies beyond them.

As a scholar of religion, I’ve been involved in translating into English one of the Mandaeans’ sacred texts, known as the Mandaean Book of John. Working in this area has also connected me with the living tradition and persuaded me that more people need to know about Mandaeans.

The ancient roots of Gnosticism

Mandaeism, like other forms of Gnosticism, is an esoteric religion whose literature remains mostly in the hands of priestly families. Their sacred texts are written in a distinctive alphabet used only for that purpose. The contents and meaning of these works are largely unknown even to most Mandaeans, never mind others.

But the Mandeans’ alternative view has periodically attracted popular interest. In the 19th century, their most important sacred text, the Great Treasure or Ginza Rba, was translated into Latin. That is believed to have contributed to the heightened interest in esoteric mysticism and spirituality in that era. However, this was largely among people who had no contact with or real awareness of the Mandaeans in the present day.

Baptism: The core of Mandaean religion

The Mandaeans’ central ritual is baptism: immersion in flowing water, which is referred to in Mandaic as “living water,” a phrase that appears in the Bible’s New Testament as well. Baptism in Mandaean faith is not a one-time action denoting conversion as in Christianity. Instead it is a repeated rite of seeking forgiveness and cleansing from wrongdoing, in preparation for the afterlife.

“Baptist” today usually denotes a form of Christianity, but Mandaeans aren’t Christians. They have a special place, however, for the individual who is said to have baptized Jesus, namely John the Baptist. The Mandaean Book of John, which I was involved in translating, tells stories about John the Baptist and attributes speeches to him containing various ethical teachings.

In the first half of the 20th century, the Mandaeans received significant attention from New Testament scholars who thought that their high view of John the Baptist might mean they were the descendants of his disciples. Many historians think that Jesus of Nazareth was a disciple of John the Baptist before breaking away to form his own movement, and I am inclined to agree.

Whatever tensions and competition there may have been among Mandaeans, Jews and Christians in Iraq in the past, today they seek to coexist amicably, finding themselves in a context in which all minority groups face much the same struggle to survive and maintain their identity.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

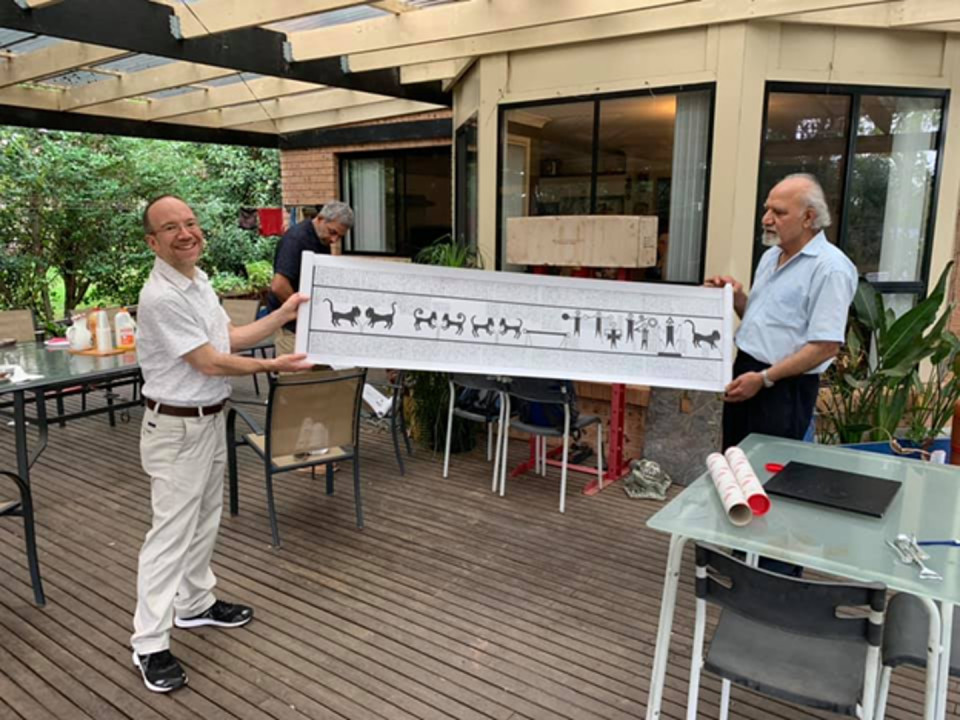

A number of Mandaean scrolls contain fascinating artwork and illustrations depicting varied images including the celestial figures mentioned in their texts, scenes from the afterlife, trees and animals. All are drawn in a style that isn’t quite like what one finds in the artwork or illustrated manuscripts of other religions. One of my favorite scenes in the scroll known as Diwan Abatur depicts people being tormented with trumpets and cymbals in purgatories through which souls are liable to pass. The point is most likely the loud noise such instruments can make, and not a negative statement about music in general.

Mandaeism today

Estimates vary as to how many Mandaeans there are today. Some can still be found in their historic homelands in Iraq and Iran. However, persecution in those places has led to the creation of small but significant Mandaean diaspora communities in such places as Australia, Sweden and the U.S.

This scattering, combined with Mandaeans’ dwindling numbers, has made it much harder for them to preserve their identity and pass their traditions along to the next generation. Mandaeans do not accept converts or consider children of marriages with non-Mandaeans to be part of their religious community, which has also contributed to their dwindling population.

There is a reasonable chance that Mandaeans may be among your neighbors, whether you live in San Diego, San Antonio or Sydney. Look for them, and you may get a chance to do more than catch a glimpse of living history.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: James F. McGrath, Butler University.

Read more:

What is the religious exemption to Title IX and what’s at stake in LGBTQ students’ legal challenge

Armenians displaced from Nagorno-Karabakh fear their medieval churches will be destroyed

Ancient texts encouraged hope and endurance when they spoke of end times

James F. McGrath received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities to support his work on the critical edition, translation, and commentary of the Mandaean Book of John referred to in this article.