Acclaimed novelist Lydia Millet brings good-neighbor tale to Unbound Book Festival

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

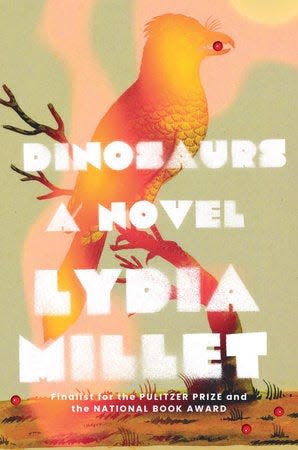

"Dinosaurs," author Lydia Millet's latest, reads like a tall tale, a story too good to be true. Yet the novel never dances to genre beats and never engages in myth-making.

To summarize its plot takes scant time, two sentences at most: Gil, a wealthy New Yorker, walks all the way to his new Arizona home, shedding the dust of a devastating heartbreak with each footfall. Upon arriving, he and his neighbors learn to live together.

That's it. That's what happens.

Yet, spreading the novel's gospel — a natural response — involves poetic pleas and inspires the absolute language of sermons. "Dinosaurs" is a book every American community needs in its libraries, civic and personal.

Slim yet endlessly soulful, "Dinosaurs" works because of where Millet's imagination took her and takes us. Embracing an "element of wish fulfillment," she created a rare and necessary character: a good neighbor.

"I wanted to spend time with this made-up person myself," Millet said of Gil.

Millet and University of Missouri professor Sam Cohen will discuss "Dinosaurs" and, no doubt, the breadth of her storied career during a Saturday afternoon conversation at the Unbound Book Festival.

More: Andrew Yoon brings the poetry of taking chances to Unbound Book Festival

How Millet found 'what to love' on and off the page

Millet, whose growing canon includes 2020's National Book Award finalist "A Children's Bible" and 2012's much-lauded "Magnificence," began "Dinosaurs" as a spiritual bookend to another early novel.

"My Happy Life" arrived in 2002, as Millet said a full and final goodbye to her 20s. A counter to earlier, snarkier figures she penned, the book traveled the "interior space of a character who was really generous and kind," she said.

The back of the book might seem grim — confined to an abandoned hospital, Millet's protagonist literally writes her story across the walls — but the work felt gentle, the author said. "My Happy Life" reflected Millet's migration away from the more judgmental spirit she harbored in her first full decade of adulthood.

"It’s actually so much harder sometimes to love other people in the world than it is to dislike them or dismiss them," Millet said.

She set out on a ministry of small steps, to "find what to love" and to let that growing fondness alter how she approached the world "in sentences," she said.

"Dinosaurs" travels the direction of this desire. Gil carries around a heart like the narrator of "My Happy Life," but lives at the opposite end of society. This distinction intrigued Millet.

She began the manuscript before the COVID-19 pandemic, revising it through lockdown. The "surreal," compounding nature of our divisions lives just outside the text, on the margins of each page. We often live at a distance, even within sight of each other.

Millet noticed this in her neighborhood, nestled within the desert around Tucson, Arizona. From a smattering of "McMansions" to single-wide trailers, and nearly every type of dwelling between and beyond, the area felt its diversity as a hindrance, not a strength. The isolation left Millet "feeling beleaguered," she said.

"I felt a longing for neighbors who might protect you or nurture you, and whom you could protect or nurture in return," she added. "There was a bit of that fantasy of care, fantasy of neighborliness."

(Almost) Saint Gil

From that fantasy, Gil emerged.

A lesser author might have crafted a hagiography around such a character. Millet wrote an "essential, fatherly instinct" into Gil; but she also allowed him a struggle she admitted to, one that stares down so many of us: a temptation toward passivity, a "failure to act."

She also made Gil a funny man.

"I can’t really write these days without humor — I shouldn’t say I can’t. Maybe I fail to sometimes," Millet said.

Against heavier circumstances and dialogue, a certain "level of wit" keeps the author interested and leavens the work, she said. Gil owns a droll sensibility, which naturally implies some measure of mocking, even if gentle and good-natured.

"Anyone who’s droll is not saint-like," Millet said.

More: How Unbound poet Jenny Molberg reclaims the power of story for domestic violence survivors

Gil's internal compass still sets him apart, guiding him to perform minor miracles: watching over neighborhood kids, believing the best about the family living closest to him, granting them the mercy of making mistakes without suffering shame, serving women at an area shelter without insisting on being treated as a "good man."

Against a desert landscape where the creatures are wild yet crave belonging, within a neighborhood that feels every inch of space between its over-watered and -manicured lawns, Gil stands out. You want to be his neighbor.

'Dinosaurs' as a homecoming

"Dinosaurs" represents a coming home for Millet on at least two levels. The book is an initial foray into writing about Arizona itself.

Writing about home once felt too much like writing about herself, Millet said, and so she avoided the entire enterprise. Tucson still feels too familiar and she's "still too cowardly" to write the city into her work, she half-joked, nestling Gil and his neighbors into a more lavish part of metropolitan Phoenix.

But she loves the place and longs to see it fulfill its own promise. In an earlier iteration of "Dinosaurs," Millet foregrounded Arizona's maverick politics, blue bleeding into red to create a color that could be purple, and the "schismatic presence" felt among neighbors during the pandemic.

That version felt too "momentary" and specific, not timeless enough, Millet said. Now all the politics and existential pull is ambient — in the air and fine dust, the spines of hardy desert scrubs and the wingbeats of pioneering birds. We need neighbors like Gil, need daily kindnesses, and we know why without Millet spooning or spelling the reasons out.

"Dinosaurs" also unites the spirit and style of Millet's work to date. "A Children's Bible" accomplished something new, she feels, joining humor and heft, the inherent smirk in earlier novels with a kinder, gentler gaze. She wants to continue in that fashion, and "Dinosaurs" captures Gil's — and her — next foot forward.

Form and function brush lips on these pages, with smaller sentences than Millet typically writes — even fragments and ungrammatical constructions, she said — giving life to the book's belief in small gestures. Against desperation and great indifference, slight movements might actually save us, the book believes. Or at least keep us alive long enough to figure out the answers.

This reorientation of the everyday possible, Millet's assertion that the fantasy within our reach, is what makes Gil worth living with — and "Dinosaurs" a worthy companion.

Millet and Cohen will convene their conversation at 1:30 p.m. Saturday at Ragtag Cinema. Visit https://www.unboundbookfestival.com/schedule for a full festival schedule.

Aarik Danielsen is the features and culture editor for the Tribune. Contact him at adanielsen@columbiatribune.com or by calling 573-815-1731. Find him on Twitter @aarikdanielsen.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: 'Dinosaurs' novelist Lydia Millet is perfect Unbound festival neighbor