The accusation against Joe Biden has Democrats rediscovering the value of due process

Business Insider

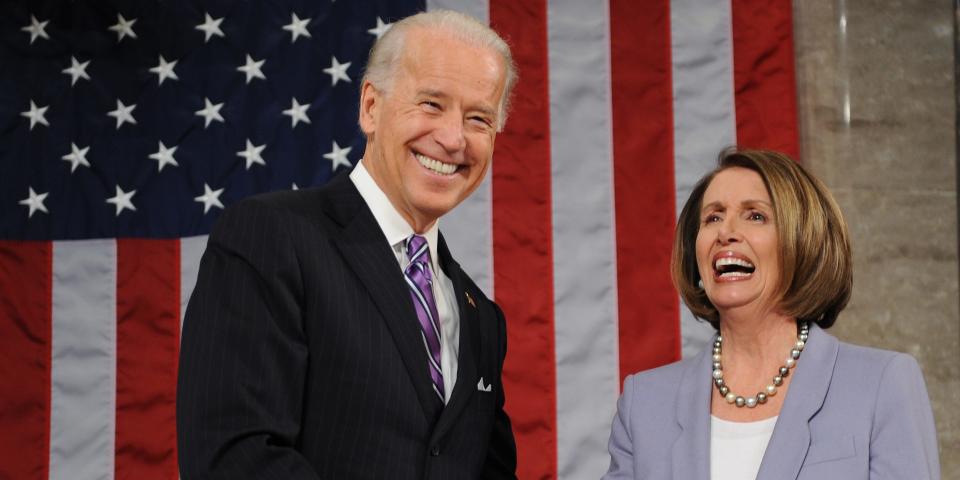

TIM SLOAN/AFP via Getty Images

Presumptions of guilt do not serve justice, they inevitably lead to false accusations and ruined lives.

That's something Democrats are rediscovering now that Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, faces a sexual assault allegation.

In the #MeToo era, "Believe Women" was meant to create a societal change that women would be taken seriously when they reported abuse.

But it was taken literally by some Democrats, including prominent lawmakers, such as Biden himself.

Due process is not exclusively for the popular. It's for both the guilty and the wrongly accused, and it's the foundation that gives just verdicts their weight.

This is an opinion column. The thoughts expressed are those of the author.

Justice requires a code.

It needs a set of guiding principles that offer the right of due process to both the unimpeachably guilty and the wrongly accused. That's the foundation that gives verdicts their weight.

Presumptions of guilt, denials as incrimination, and convictions by way of accusations do not serve justice. They inevitably lead to malicious and baseless accusations and ruined lives.

They also cheapen the experience of true victims and ultimately undermine faith in justice itself.

That's a lesson that Joe Biden and his supporters are coming around to learning, now that the former vice president and presumptive Democratic presidential nominee has been accused by former staffer Tara Reade of committing sexual assault in a Senate hallway nearly 30 years ago. Biden categorically denies Reade's accusation.

Several high-profile female Democratic lawmakers — including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Stacey Abrams, and Sen. Kirstin Gillibrand — have gone public with their support and belief in Biden's innocence, largely based on their personal experiences with him that showed no indications that he would be capable of such a crime.

And Reade's status as a Bernie Sanders supporter who has tweeted strangely supportive statements about Vladimir Putin, as well as the timing of her accusation, are being used by Biden supporters to cast doubt on her claims.

Considering the reliability and history of both the accuser and accused are things that happen when an accusation is adjudicated through due process.

The accused is given a chance to defend themself. Character witnesses can be called in support of the accused. The accuser's credibility and motives can be called into question.

But that basic code is not how Democrats have been inclined to treat sexual assault or harassment allegations since the #MeToo movement was sparked in 2017, or even before that.

"Every claim is [not] equal"

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer in 2018 tweeted "I believe Dr. Ford" in support of Christine Blasey Ford, who accused conservative then-Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her in high school.

CNN's Jake Tapper on Sunday asked Whitmer how she could so unequivocally believe in Biden's innocence now, given the fact that Ford lacked "the contemporaneous accounts" of her alleged assault that Reade has provided.

Whitmer replied that "as a survivor and as a feminist, we need to give people an opportunity to tell their story. But then we have a duty to vet it. And just because you're a survivor does not mean that every claim is equal."

That is true, but it doesn't address the discrepancy in Whitmer's personal standard of evidence. And it's not how Democrats have dealt with the issue of adjudicating sexual assault and harassment claims over the past decade.

In 2011, the Obama administration changed its Title IX guidelines, which "prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex in any federally funded education program or activity."

The new guidelines broadened the scope of offenses and drastically lowered the evidentiary standards for sexual assault and harassment claims on college campus. They essentially did away with due process.

Under the new system, a student or faculty member could be accused, found "guilty," and expelled from campus without ever having been given the opportunity to view and dispute the evidence used against them, much less be able to rely on the assistance of legal counsel.

As feminist legal scholar Janet Halley put it, the new system was bound to produce "false positives."

Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos mostly reversed the Obama-era rules this week, and Biden promised to reinstate them if elected. However, if Biden were to face such a hearing in a college setting based on Reade's accusation, he wouldn't have the right to scrutinize the evidence, and would likely face consequences as a result.

An Orwellian tale of presumed guilt by accusation on campus — under the Obama guidelines — was recently recounted at length in The New York Times Magazine. The fact that the accused was a married professor with an impeccable reputation didn't matter, the letter of the "law" required her to prove her innocence, not the other way around.

After a financially and emotionally draining saga, the accused was able to prove that the "accusers" were not even actual people, much less actual victims (they were the malicious creations of a professional rival with an ax to grind).

But this wasn't a flaw in the system, this was the design of the system. Accusers didn't have to show their face or evidence, they just needed to accuse. In this case, it was to an anonymous email account set up by the school to field Title IX complaints.

And while the new guidelines were created with the best of intentions — to make it easier for sexual assault victims to file complaints against their assailants without having to endure further pain and humiliation — they provided an easily exploitable avenue for false accusations.

No system of justice will ever be perfect, and no system can remove the pain felt by victims. But a system that presumes guilt will only create more victims.

Relearning due process

Harvey Weinstein's unmasking as a pervasive and horrific sexual abuser launched what became known as the #MeToo movement in 2017. A much-needed reckoning followed.

A substantial number of wealthy and powerful men were finally held to account for their long-tolerated abuses. Casual forms of physical and verbal workplace harassment that had been commonplace were now banished as beyond the pale.

"Believe women" became a mantra in the movement. The phrase was meant to represent a push toward societal change that women's claims of abuse would be taken seriously.

House Speaker Pelosi tweeted it with a hashtag in 2017. Kirstin Gillibrand has used the phrase repeatedly. And though some of its adherents don't want to admit it now, it was taken literally by many. An accusation was considered a verdict.

This was always an untenable position. If "believe women" was literal, then due process was over.

Now that Joe Biden faces what many consider a credible sexual assault accusation, the goalposts are moving.

On September 16, 2018, Christine Blasey Ford's confidential letter to California Sen. Dianne Feinstein went public. In it, Blasey Ford accused then-Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her 36 years earlier while they were both in high school.

A day later, Gillibrand tweeted "Professor Blasey Ford showed immense courage and bravery by coming forward to tell her story. I believe her and will stand by her. We must all come together to support her."

The subsequent hearings showed that belief in Blasey Ford's accusation generally broke along party lines. Many of Kavanaugh's long-time friends and associates came forward vouching for his character, saying there had been nothing in his long judicial career or personal life that indicated he was capable of such behavior.

As with Kavanaugh, a major part of how credible you find the accusation against Biden depends on how you feel about the former vice president, how you gauge the consistency of the accuser's story, how you feel about the accuser's potential motives — among other factors.

In other words, it's complicated.

The accusation requires thorough adjudication, which would hopefully give the public enough information to decide whether or not Biden should be president. The verdict in the court of public opinion should be rendered thoughtfully, not emotionally or reactively. The full truth may never be found, but at least something approximating due process is playing out in public.

Now that he's accused, Biden and his supporters say "believe women" isn't meant to be taken literally. What it really means is listen to women, and then vet their accusations, which could be baseless.

But that was simply not the prevailing post-#MeToo sentiment.

House Speaker Pelosi last week rebuffed a reporter's question about why she hasn't called for an investigation into Biden's conduct as a senator, saying she didn't need a "lecture." Pelosi added that while she supports the #MeToo movement, "There's also due process and the fact that Joe Biden is Joe Biden."

Pelosi's right, there is due process. And she's completely entitled to believe Joe Biden based on her impression of his reputation. But what misses is that due process and a presumption of innocence should be for everyone, regardless of how one feels about the accused.

Without due process, justice is just a popularity contest.

Read the original article on Business Insider