Adam, blacksmith and champion of freedom, dies without honor of last name | Righting the past

Editor’s note: This is the thirteenth in a series of historical obituaries written today to honor the men and women of the past who were denied the honor at the time of their death because of discrimination due to their race and/or gender.

On an unknown date, in an unmarked location, after an extraordinary life, a man named Adam died. Even the date and place of his birth — and the names of those in his family — are lost to the pages of history. Yet his story endures.

Adam survived a terrible injustice during his life. Like many enslaved men in Pensacola, Adam’s labor was rented out to the federal government. In Pensacola, Army and Navy officers relied on a system of slave rentals to build and maintain a sprawling military installation. These men and women built Fort Barrancas, Fort McRee, Fort Pickens and the Pensacola Navy Yard. From 1840 to 1860, even after the completion of the three forts, the Navy alone rented upwards of 200 enslaved men each year.

What is 'Righting the past?' Their history wasn't just forgotten, it was buried. Today we tell their stories.

Righting the past: Viola Washington Edwards, pioneering health care provider, dead at 70

Twenty-one years old in 1850, Adam labored as a blacksmith in the Pensacola Navy Yard. The Navy paid his enslavers, Josiah Q. and Lucinda Guild, $1 per day for Adam’s labor. Described as “nearly free” and “an intelligent fellow,” Adam was valued at $1,800 — repugnantly equal in purchasing power to about $70,000 today.

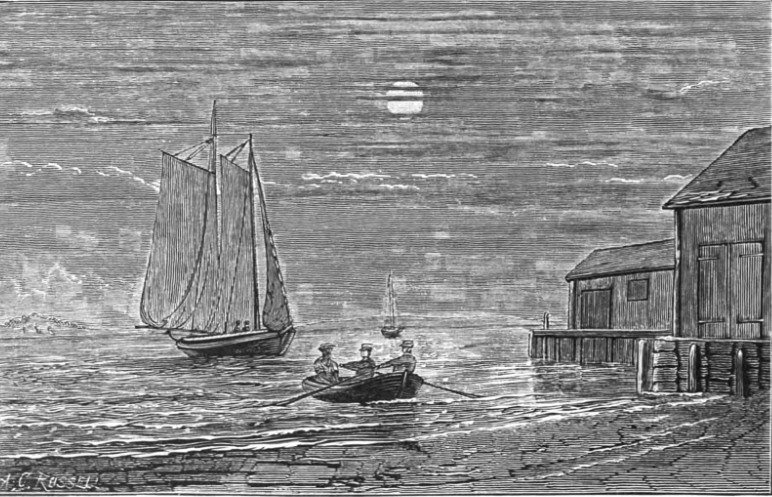

Longing to be free, in June 1850, Adam snuck aboard the ship Mary Farrow which was anchored in Pensacola Bay. He left his mother and sisters behind. Bound for Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the ship cleared Pensacola Pass and entered the Gulf of Mexico. Adam could finally breathe a sigh of relief, but only for a moment. His dangerous maritime voyage on the Underground Railroad had only just begun.

The escape of freedom seekers like Adam on the Underground Railroad enraged southern enslavers. Freedom seekers and their allies justly robbed enslavers of their wealth and destabilized white supremacy. Powerful interests lobbied to protect the enslavers. When Adam escaped, Congress was considering a law meant to disrupt the Underground Railroad — the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act.

Even as lawmakers debated, the Mary Farrow crossed the Gulf of Mexico with its cargo of lumber and one stowaway. After three days at sea, Captain Timothy Warren discovered Adam aboard the ship. Outraged, Warren ordered Adam to be thrown overboard and dragged by rope beneath the ship’s hull, a notorious punishment known as keelhauling. The crew intervened and protected the freedom seeker for the rest of the journey.

Upon reaching Portsmouth, Warren went ashore to report Adam. Meanwhile, “the friends of liberty” acted. Allies sailed to the ship and found Adam, “the panting fugitive from oppression.” But Warren soon returned to the ship.

Righting the Past: Mercedes Vidal, center of early territorial scandal, dead at 84

Righting the past: Veteran Henry Stalburt, champion of freedom, dead

Warren refused to let Adam go ashore. Fearing his doorway to freedom was closing, Adam “sprang with all the desperate energy of the flying fugitive” into a boat beside the Mary Farrow. But Warren delivered “a stunning blow” upon Adam’s head and dragged him back to the vessel. Adam’s allies rushed back to the city, where they found legal help from someone “favorable to the cause of human rights.”

Facing a legal challenge, Warren ordered Adam to leave the ship. With the help of Portsmouth’s anti-slavery network, Adam made his way to “the free dominions of Queen Victoria in the North.”

A month after Adam reached Canada, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act became law. With the law’s passage, life in the United States grew more dangerous for formerly enslaved and free Black Americans.

Heroic actions of freedom seekers like Adam forced a nation to confront one of the gravest crimes against humanity. In his pursuit of liberty, Adam embodied the spirit of America.

Today, the route Adam took out of Pensacola Bay is listed with the National Park Service’s National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program. In the mid-1800s, the pass was closer to Fort Pickens and is within the current boundaries of Gulf Islands National Seashore.

Designating Pensacola Pass as an Underground Railroad site provides present and future generations with opportunities to learn about the cruelty of human slavery and courageous individuals like Adam. His heroic actions in his known life and unknown death provide an example of bravery in the pursuit of liberty.

This article originally appeared on Pensacola News Journal: Adam, blacksmith and champion of freedom | Righting the past