Adding Supreme Court justices? Progressives may be on collision course with Joe Biden

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

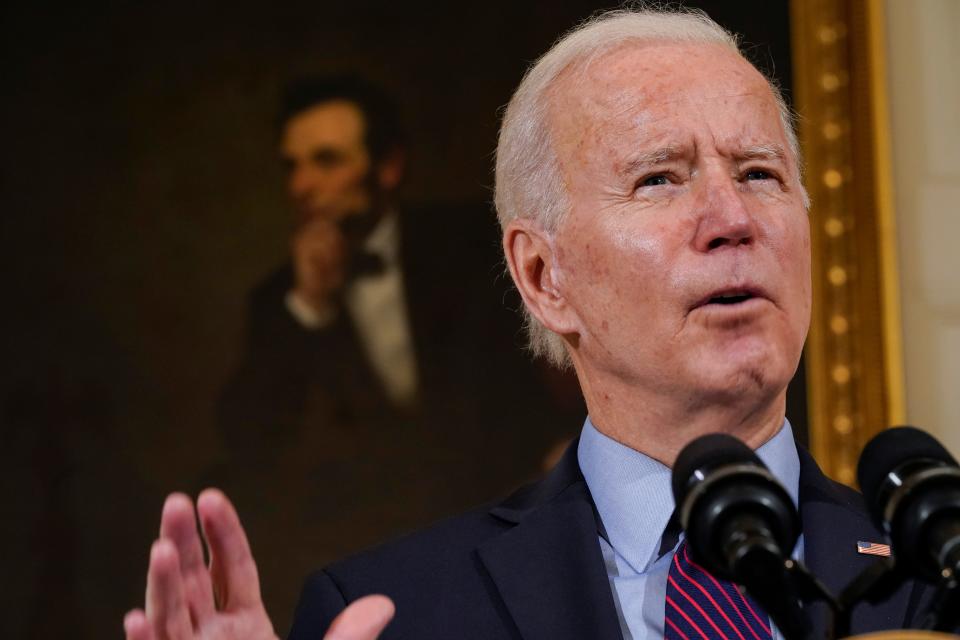

WASHINGTON – A number of progressives appear to be heading toward a showdown with President Joe Biden over a new commission that will study changes to the Supreme Court, underscoring the tricky politics at play for an administration that is aiming for bipartisanship but also hoping to retain support from the left flank.

Biden proposed the commission in October to head off a push by liberals to expand the number of justices on the nine-member court – an effort prompted by the quick confirmation of Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett days before the Nov. 3 election. Her narrow approval gave conservatives a 6-3 advantage, the most lopsided split since the 1930s.

Several progressives said they remain hopeful about the commission's work but are also sounding early alarms over its composition and timeline. The panel itself was widely seen as a way for Biden to punt on a proposal that has been politically poisonous since President Franklin D. Roosevelt's failed attempt to "pack" the court in his second term.

"The commission has an opportunity to do something important," said Aaron Belkin with Take Back the Court, a group that advocates for adding justices. "At the same time, we are very concerned because commissions are often places ideas go to die."

New justice: Barrett steers the Supreme Court to the right, but not toward Trump

The push for change – more justices or term limits or a code of ethics are among the ideas the groups are seeking – has put a squeeze on the Biden White House, emphasizing the gap between liberals who want the new president to mitigate the outsized impact former President Donald Trump had on the federal judiciary and a new administration that won power in part on a promise of moderate leadership.

After Senate Republicans stymied President Barack Obama's 2016 nominee for the court, Merrick Garland, Trump managed to seat three associate justices in four years: Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Barrett. Biden has since nominated Garland, a federal appeals court judge, as his attorney general.

The pressure for some kind of overhaul has not come exclusively from left-leaning groups. Eric Holder, who served as attorney general under Obama, said during a recent Brookings Institution event that federal courts "badly need reforms" and asserted that Democrats are "uncomfortable" with using their power in a way that Republicans have not been.

Biden's last substantive remarks on the issue came just before the election. He told CBS News in October that the process of confirming justices was "getting out of whack" but added that "the last thing we need to do is turn the Supreme Court into just a political football."

Barrett took her seat on the court days later.

Short on time

Leaders at a half dozen progressive groups said that they are mostly withholding judgment on the commission until more details are clear. Still, some are casting sideways glances at a few details that have emerged. Biden set a six-month deadline for the panel's recommendations – a timeline some say is far too long.

Expanding the size of the Supreme Court won't win Republican support and it has already made some centrist Democrats squeamish. Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., a key swing vote, said in October that he opposes adding justices. If Republicans recapture control of either the House or Senate in 2022, they will almost certainly shelve the idea.

"We don't have six months to study a question whose answer is already known," Belkin said.

More: Biden's influence on judiciary may be limited despite talk of 'court-packing'

More: The Kamala Harris-Joe Manchin dust-up explained - and why it matters for Biden

Another factor, experts said, are the justices themselves. If the new 6-3 majority moves quickly to assert itself on divisive issues such as abortion or guns, that could galvanize support on the left for change. On the other hand, if it pumps the brakes on those controversial cases, that could make it harder for progressives to organize.

"What political science has said is that when Congress introduces bills – when there's political pressure to reform the court – in general, the court backs down," said Joshua Braver, a University of Wisconsin law professor who has studied past campaigns to change the court. "As a matter of institutional heft, Congress has so many ways to strip its power."

Who will serve?

The sense of urgency has set off a scramble among progressive groups to assess who will serve on the commission, and what its mission will be.

Biden campaign lawyer Bob Bauer, a former Obama White House counsel, will serve as co-chair, along with Cristina Rodríguez, a Yale Law School professor and former official in the Obama Justice Department. A Biden administration source familiar with the details of the commission confirmed the appointments on the condition of anonymity to discuss details not yet publicly announced.

Neither Bauer nor Rodríguez responded to questions about the commission.

The administration source said recruitment for other seats has "progressed significantly" but was not yet complete. Biden "remains committed to an expert study of the role and debate over reform of the court" the person told USA TODAY, adding that the president will have more to say "in the coming weeks."

Biden had previously said he would name progressives and conservatives to the group. But some progressives are grumbling about the names Biden is reportedly considering, including Jack Goldsmith, a Harvard Law professor who worked in the Bush administration. Goldsmith, whose name appeared as a potential pick in a recent Politico article, has drawn the ire of liberals in part for a 2018 magazine piece in which he praised conservative Kavanaugh, then a high court nominee, for his "careful, honest, detached interpretation of the Constitution."

"The fact that someone like that is put on suggests we're going to have some real problems; I hope I'm wrong," said Molly Coleman, executive director of the People's Parity Project, a group of law students and lawyers aiming to change the judiciary.

Goldsmith did not respond to a request for comment.

Coleman's concerns aren't limited to the appointment of a single conservative member. Like other progressives, she wants the commission to have a diversity of legal experts, including some who have advocated on behalf of the issues before the court rather than a group of high-powered political and corporate attorneys.

"This isn't an academic project," she said. "We don't want to end up with a commission that only reflects the best that Harvard, Yale and Georgetown have to offer."

Term limits? Adding more lower court judges?

Advocates for expanding the court note the number of Supreme Court justices isn't set in the Constitution and frequently changed in the past – often for political reasons. Congress expanded the court to 10 during the Civil War to ensure a majority for Union policies, cut the nation's highest bench to seven to deny President Andrew Johnson nominations, and ratcheted it up to nine to give President Ulysses S. Grant majority support on the court for his monetary policies.

Opponents, including the late Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, say adding justices would harm the court, which draws authority and respect from the notion that it operates independently and above the fray of partisan politics. Ginsburg, a progressive icon, died last year.

"If anything would make the court look partisan," Ginsburg told NPR in 2019, "it would be that – one side saying, 'When we're in power, we're going to enlarge the number of judges, so we would have more people who would vote the way we want them to.'"

Progressive groups are also pushing for a number of slightly less politically charged ideas: Term limits for justices, set perhaps to 18 years; a code of ethics; a more formal and enforceable process for recusals; and an expansion of lower courts, not only to offset the barrage of Trump appointees, but also to deal with growing caseloads.

Brett Edkins, political director at the advocacy group Stand Up America, said he was encouraged that Biden "recognizes there's a problem."

But recognition alone, he said, won't satisfy progressives.

"The commission is the start," he said. "We expect results at the finish."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Supreme Court expansion pits progressives against centrist Joe Biden