Adnan Syed's Murder Case Has Turned Into A Thorny Fight About Victims' Rights

This is an excerpt from our true crime newsletter, Suspicious Circumstances, which sends the biggest unsolved mysteries, white collar scandals, and captivating cases straight to your inbox every week.Sign up here.

The legal saga of “Serial” subject Adnan Syed — whose conviction for the murder of his ex-girlfriend, Hae Min Lee, was vacated last September and the charges dropped against him, only to be reinstated in March — saw another extraordinary development last monthwhen the Maryland Supreme Court agreed to hear two petitions in the case: one from Syed and the other from Lee’s brother, Young Lee. The court will hear arguments from both sides in October.

This is a big deal.

Obviously so for Syed, whose life sentence for murder remains at stake, though he has remained out of prison while the appeals play out. But in addition to that, it could radically alter victims’ rights to participate in certain court proceedings.

So how did we get here?

The state’s original case against Syed had seemed to be straightforward: 18-year-old Lee was yet another victim of deadly intimate partner violence, strangled by a jealous, jilted boyfriend, prosecutors said. It was only unusual because Syed’s first trial ended after just three days because jurors overheard a sidebar conversation they weren’t supposed to and the judge declared a mistrial. Lee’s family sat through not only the first trial’s opening statements but the trial to follow, hearing weeks of testimony and grisly details about their daughter’s murder. A jury found Syed guilty in February 2000 and a judge sentenced him to life plus 30 years in prison.

An endless number of court rulings since then have seen heartbreak and hope for Syed and his supporters, whose numbers grew exponentially after the massive success of“Serial.” The 2014 podcastcast Syed as a sympathetic character (host Sarah Koenig gushed about his “giant brown eyes like a dairy cow” and said “he just doesn’t seem like a murderer”) in a murder mystery that its record number of listeners tried to solve. It examined timelines and routes and phone calls, interviewed key players, unearthed a witness who claimed Syed had an alibi (a court would later find contradictions in her account), flagged inconsistencies and questioned whether his abrasive attorney had bungled his defense. The podcast ended without a resolution, but a rallying cry formed in its wake: #FreeAdnan.

Adnan Syed was released from prison in September after his murder conviction was overturned.

Syed, now 42, hadremained behind bars for 23 years, losing a number of appeals and challenges. After “Serial,” however, a judge in 2016 granted him a new trial.

“It remains hard to see so many run to defend someone who committed a horrible crime, who destroyed our family, who refuses to accept responsibility, when so few are willing to speak up for Hae,” Lee’s family said in a statement at the time. “Unlike those who learn about this case on the internet, we sat and watched every day of both trials — so many witnesses, so much evidence.”

That new trial never happened: After a number of appeals, Syed’s bids for freedom were ultimately rejected when the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear his case in 2019.

Then came a bombshell: On Sept. 14, 2022, prosecutors— not Syed’s defense — asked a judge to overturn his conviction.In their motion to vacate, prosecutors said that after a yearlong joint investigation with the defense, they determined that information had been withheld from Syed at trial, and they challenged the reliability of trial evidence, citing new DNA findings and “alternative suspects,” whom they did not name.

An even bigger bombshell was dropped just days later.

On Sept. 19, the judge threw out Syed’s conviction and ordered his immediate release. Lee’s family members were given just days’ notice and were unable to attend the hearing in person.

Young Lee ended up joining remotely via Zoom, saying he felt “betrayed” and “blindsided” by the prosecution’s motion to vacate. “This is not a podcast for me,” Lee said, referring to “Serial.” “This is real life — a never-ending nightmare for 20-plus years.”

The Lee family appealed, saying their right to “meaningfully participate” in the hearing had been violated. But they were caught off guard again when, just weeks later, prosecutors dropped the charges against Syed. Then-Baltimore State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby, who had been indicted earlier that year for federal perjury and mortgage fraud charges, said in a news conference that Syed had been “excluded” as a suspect because trace DNA from multiple people — none of them Syed — was found on Lee’s shoes in a second round of testing. (“These tests never cleared Syed or implicated alternative suspects,” the Lees pointed out in their state Supreme Court petition.)

The Lee family wasn’t told the charges were being dismissed — they found out through media reports.

“The family received no notice and their attorney was offered no opportunity to be present at the proceeding,” said Steve Kelly, the Lee family’s lawyer. “By rushing to dismiss the criminal charges, the State’s Attorney’s office sought to silence Hae Min Lee’s family and to prevent the family and the public from understanding why the State so abruptly changed its position of more than 20 years. All this family ever wanted was answers and a voice. Today’s actions robbed them of both.”

Then-Baltimore State's Attorney Marilyn Mosby announces her office has dropped charges against Adnan Syed in the 1999 killing of Hae Min Lee.

Then the record scratch.

Syed’s and his supporters’ celebration of his release came to an abrupt halt in March when the Appellate Court of Maryland reinstated his conviction and ordered a new hearing. The judges ruled that Young Lee’s rights had been violated and said they shared “many of [his] concerns about how the proceedings were conducted” — but limited the ruling to whether he was given adequate notice to appear. Still, the court called for more transparency from prosecutors, telling them to present evidence supporting their motion to vacate while “stating its reasons in support of its decision.”

That still felt lopsided to the Lee family.

Because the prosecutor and defense attorneys were aligned, no one could challenge their findings, so the judge’s decision to overturn Syed’s conviction was essentially “based on speculation, conjecture, and innuendo alone,” attorneys for Lee said. In a remarkable move, they asked if the Lee family could step up in the courtroom, petitioning the state Supreme Court to give crime victims the opportunity to be heard and challenge evidence in such hearings.

“Our system of justice relies on the adversarial process,” attorneys for Lee said. “Deciding a case based on untested, one-sided claims would mirror the abuses of authoritarian regimes.”

In his own state Supreme Court petition, Syed’s attorneys disputed Lee’s claims of one-sidedness, saying that there was “nothing inherently suspicious or nefarious about an agreed upon resolution to a case,” and that granting Lee’s request would be “wildly impractical, if not disastrous.”

After the state Supreme Court hearing in October, what’s next?

Adam Ruther, a criminal defense attorney and former Baltimore City prosecutor, explained the potential outcomes in a phone interview with HuffPost.

What does a ‘win’ for Adnan Syed mean?

The Maryland Supreme Court could rule that the appeals court got it wrong — essentially saying that Lee “was able to participate — albeit with late notice — was able to call in, and that’s enough to satisfy the victims’ rights statute,” Ruther said. An “outright win” for Syed would see his conviction again overturned, the charges against him dropped, and his freedom secured.

In other words, it would affirm the belief held by millions — including prosecutors themselves — that Syed had been wrongfully convicted. Erica Suter, his lawyer and the director of the Innocence Project Clinic at the University of Baltimore School of Law, told HuffPost that both Syed and Lee’s family have been punished by the case. “[It] has caused profound harm for both Hae Min Lee’s family, who lost their daughter and sister and have yet to receive true answers about her death; and for Adnan and his family, who lost their son and brother for more than 20 years for a crime he did not commit,” she said.

“Wrongful convictions leave a trail of victims in their wake,” added Suter, who played an instrumental role in securing Syed’s release. “The Supreme Court’s review is not about who is a victim, but how the system redresses injustices caused by prosecutorial misconduct in cases like Adnan’s.”

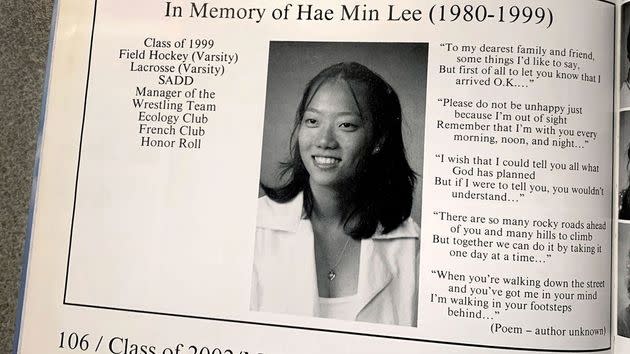

A tribute to Hae Min Lee, class of 1999, in a Woodlawn High School yearbook.

A ‘win’ for Lee is a little more complicated.

At its simplest, the state Supreme Court could favor Lee by affirming the appellate court’s ruling that the existing victims’ rights statute was not followed — “at least in the spirit, if not the letter, of the law,” Ruther said, and “the Lee family should have had more notice and an opportunity to participate more meaningfully in the proceedings.” It would be up to the state’s attorney’s office to “redo” the hearing where the prosecutors said they didn’t have faith in the original conviction. “They could do that exact same hearing,” Ruther said, “except this time, giving full voice to the victim’s right to be there and be heard.”

A bigger win for the Lees — and what the state Supreme Court is now allowing them to argue — would be to grant them a “substantive role” by presenting evidence or cross-examining witnesses themselves. “They’re saying, ‘Look, if the state isn’t interested in protecting this conviction, we should be allowed to as the victim,’” Ruther said. It would be an unprecedented expansion of victims’ rights and give the Lees a chance to question why, for example, evidence from the original investigation and trial is now being discounted by prosecutors, if there’s disagreement among experts on what the trace DNA evidence means, and whether alternative theories about who killed Hae Min Lee were really likely to sway a jury.

It’s a wild scenario to contemplate.

“It would be the defense and the state arguing to overturn a conviction with the victim’s family arguing why the conviction has integrity and should stay exactly as it is,” Ruther said. “And then the court has to decide that in that adversarial setting — when normally the adversarial parties are the defense and the state. The prosecutor is normally trying to defend the conviction.”

Metaphorically, the prosecution and defense would be scooching their tables together while a third one is brought in for the “victim’s team.”

That’s not too much to ask in the eyes of the Lee family.

“The State of Maryland supports victims and their families with rights acknowledged by Maryland’s own state constitution and statutory scheme,” Young Lee’s attorney David Sanford said in a statement provided to HuffPost after the state Supreme Court granted his petition. “We will urge the Maryland Supreme Court to recognize those rights by allowing Young Lee and his family the opportunity to challenge the state’s evidence, to the extent it has any evidence, suggesting Adnan Syed did not murder Young Lee’s sister 23 years ago.”

At the core of victims’ rights is the legal requirement that the state treat crime victims with dignity, respect and sensitivity, he added.

“That right to dignity means here that Young Lee should have the right to meaningfully participate in a hearing that could potentially vacate a murder conviction,” Sanford said.

And though that would fundamentally change how these hearings operate, denying that right to participate could have grave consequences for the legal system, Russell Butler, an adjunct professor at the University of Baltimore School of Law, told HuffPost.

“Ignoring the interests of victims,” he said, “is contrary to having justice for all.”