Advocates say excited delirium provides cover for police violence. They want it banned

Bella Quinto-Collins was celebrating her 21st birthday with her family on Sunday when she got the news they'd all been waiting for: California had just become the first state to ban “excited delirium” as a diagnosis and cause of death.

The announcement came nearly three years after Quinto-Collins had watched in horror as two Antioch police officers restrained her brother, Angelo Quinto, and one knelt on his neck for nearly five minutes while the Navy veteran was having a mental health crisis. Quinto, 30, died in the hospital in December 2020, and the Contra Costa County Coroner’s Office later listed his cause of death as “excited delirium syndrome."

Excited delirium is not recognized by many major medical groups. But it has been cited as a cause or contributing factor in dozens of deaths in police custody, which sometimes involve mental health issues and drug use, and critics say it has been disproportionately used in cases involving Black men. California's historic move came days before a major medical professional organization voted to formally disavow research which experts say has helped officers in many of these cases evade accountability.

Quinto-Collins hopes the new legislation will prevent other families from having to endure the same situation.

"We were just so thrilled, but also sad at the same time," she said. "And I really felt like well, maybe my brother was trying to give me a gift for my birthday that this legislation would be signed."

Quinto-Collins and other advocates, attorneys and lawmakers said they hope that other states will enact similar legislation and that these changes will force an end of the use of the controversial condition.

"This is a huge win. This is really amazing," said Albert Fox Cahn, founder of Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, a New York non-profit advocacy organization and legal services provider that helped draft the California bill. "To see this in the largest state in the country to me is just a prelude to a national movement to abolish excited delirium, and more broadly, to continue to hold police accountable for the way they use violence."

What is excited delirium?

Excited delirium is described as a collection of symptoms "broadly characterized by agitation, excitability, paranoia, aggression, great strength and unresponsiveness to pain, and that may be caused by several underlying conditions, frequently associated with combativeness and elevated body temperature," in a 2011 Department of Justice report on deaths following exposure to tasers.

Police have violently restrained people exhibiting symptoms associated with excited delirium using techniques such as prone restraint, which can be deadly, according to a 2022 Physicians for Human Rights report. Excited delirium is then cited as causing or contributing to the death instead of law enforcement actions, the report said.

While excited delirium today is often linked to deaths in police custody, the term was first cited in the 1980s by a forensic pathologist as the cause of death of Black men and women in Miami, some of whom had small amounts of cocaine in their systems, according to Joanna Naples-Mitchell, a human rights lawyer and co-author of the report.

Though the theory was proven incorrect in several cases, the pathologist "continued to push this extremely racialized, gendered theory of death from otherwise nonlethal amounts of cocaine and it spread," said Naples-Mitchell.

She said a group of experts and physicians - some of whom worked as defense experts for the company that makes tasers now called Axon Enterprise - produced "extremely flawed studies" and continued to promote the theory two decades later. Axon did not respond to a request for comment from USA TODAY.

Naples-Mitchell said some of those experts went on to write a 2009 white paper that was adopted by the American College of Emergency Physicians. A study published in the Western Journal of Emergency Medicine in January found the symptoms listed in the paper rely on "persistent racial stereotypes."

The Physicians for Human Rights review ultimately determined there is no clear and consistent definition of excited delirium, it is not a valid diagnosis and should not be cited as a cause of death.

'Excited delirium' It's cited as factor in many fatal police restraint cases. Some say it's bogus.

How often does 'excited delirium' occur?

A 2020 USA TODAY Network investigation found 85 deaths were attributed to excited delirium in Florida from 2009 to 2019 and about two-thirds of those involved in-custody deaths or other interactions with law enforcement, Florida Today reported. A 2017 investigation by the American-Statesman, also part of the USA TODAY Network, revealed more than one in six of the 289 non-shooting deaths of a person in police custody in Texas since 2005 have been attributed to excited delirium.

"There are hundreds and hundreds of these cases, certainly, potentially thousands of cases if you looked at all the jurisdictions," said Michael Freeman, co-author of a 2020 study that found no evidence excited delirium can cause death without some form of restraint.

There are no official statistics on in-custody deaths attributed to excited delirium, according to Julia Sherwin, a co-author of the Physicians for Human Rights report. Sherwin said even when an official autopsy report lists excited delirium as a cause of death, such as in Quinto's case, it cannot be statistically recorded that way because there is no code for excited delirium in the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases.

But, she noted, excited delirium has come up as a defense in every case where a person has died of asphyxia after being restrained she's handled in the past 20 years, including a federal case that goes to trial next month. She said defense attorneys often hire forensic pathologists or emergency physicians, often from the same small group, to testify.

"When people die after being asphyxiated to death by law enforcement, the defendants want to point to some other cause of death so that they can say 'the person did not die from restraint asphyxia the person died from this phantom condition: excited delirium," she said. "So they're using it to try to escape accountability, essentially."

Excited delirium has come up in several recent high profile deaths in police custody, including the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Former police officer Thomas Lane could be heard on body camera footage of the struggle expressing concern that Floyd might be experiencing excited delirium.

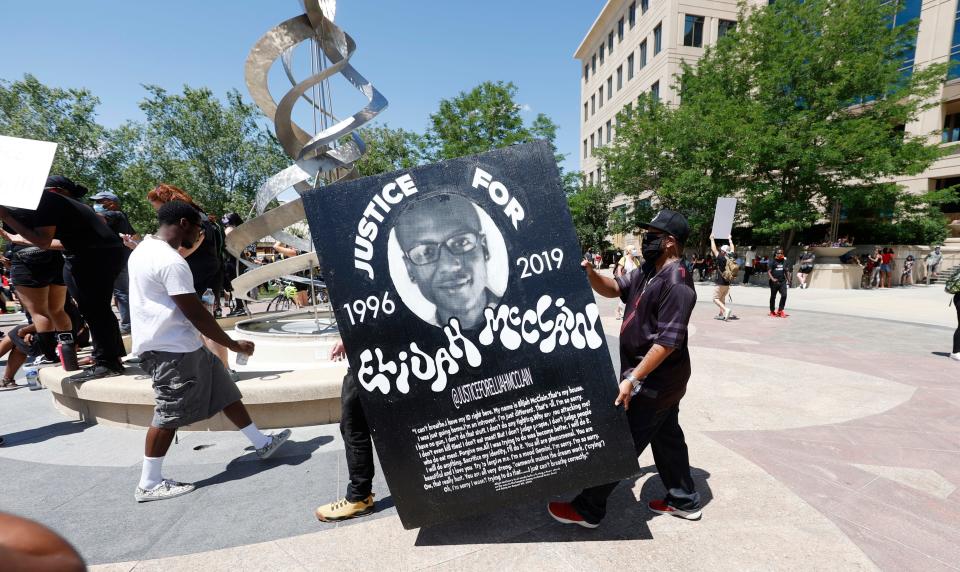

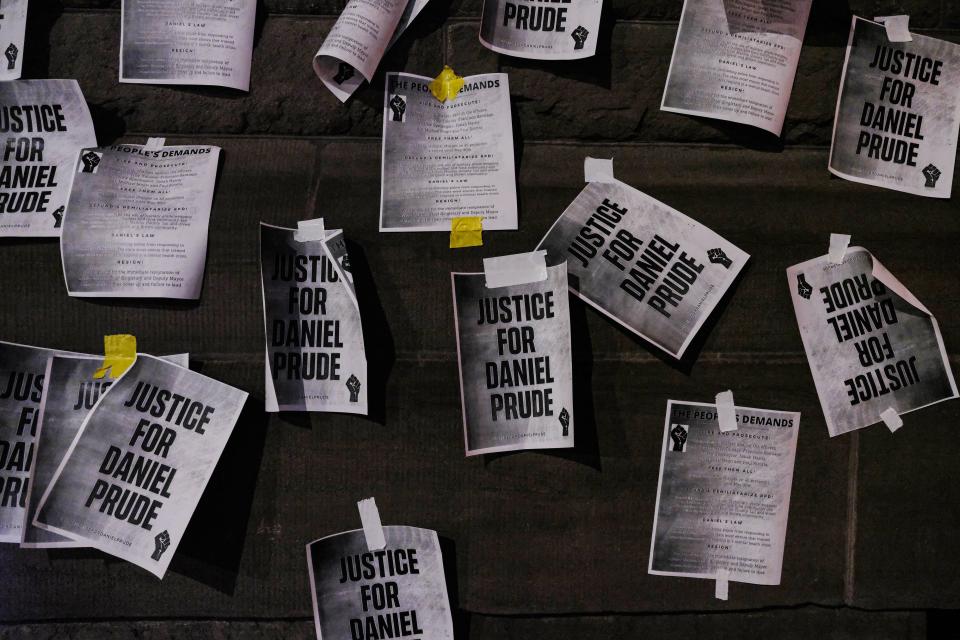

The theory was also cited in the 2019 death of Elijah McClain in Aurora, Colorado, the 2020 death of Daniel Prude in Rochester, New York and multiple cases USA TODAY examined in which people told officers they couldn’t breathe before dying of asphyxiation.

"The term has come to be used as a catch-all for deaths occurring in the context of law enforcement restraint, often coinciding with substance use or mental illness, and disproportionately used to explain the deaths of young Black men in police encounters," the report reads.

Will other states ban excited delirium?

California's new law was prompted by the death of Quinto, according to the bill's sponsor, Assemblymember Mike Gipson.

"California is the first state in terms of taking this humongous step," said Gipson, a former police officer. "I'm hoping since we have crossed over, if you will, that other states will rally and pass laws similar to what California has."

In Colorado, where jury deliberations are underway in the trial of two officers charged in connection with McClain's death, state Rep. Judy Amabile said she plans to introduce similar legislation. Amabile said she's "pretty optimistic" her fellow legislators will support the bill, which will also explicitly prohibit law enforcement from training on excited delirium.

"It's a made-up term that doesn't actually mean anything and should not be part of our terminology that we use when we're dealing with people in a crisis of one kind or another," she said.

Cahn, of Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, said he expects there will be a push to adopt similar legislation in New York, where Prude died, and the group plans to make the model legislation accessible to advocates around the country.

Sherwin said she has reached out to Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison about introducing a similar law. The Minneapolis Police Department and mayor's office previously said the city had stopped training on excited delirium, but the Star Tribune obtained a video of the new training last year showing the department was still teaching officers how to respond to it.

Sherwin, a California civil rights attorney, said the California law, which goes into effect in January, will "go a long way to finally putting an end to the theory." But she said a federal law "that squashes this once and for all," is still needed.

"[Excited delirium] is, I think, dying a slow death," she said.

'A myth that is not going to be resurrected'

The American Medical Association, the American Psychiatric Association and the National Association of Medical Examiners have rejected excited delirium as a diagnosis. On Thursday, the American College of Emergency Physicians' board of directors voted to withdraw its approval of the 2009 white paper, which has been cited as a justification for allowing expert witness testimony on excited delirium in court, according to the Physicians for Human Rights report.

The group called the paper "outdated" in a statement and said "the term excited delirium should not be used among the wider medical and public health community, law enforcement organizations and ACEP members acting as expert witnesses testifying in relevant civil or criminal litigation."

Brooks Walsh, an emergency physician in Connecticut who presented the resolution to disavow the paper last week, said though expert witnesses can still cite other research, Thursday's vote means they can no longer "use the authority of ACEP to bolster your position."

"I think we should have tackled this earlier," he said. "Now, California legislators have taken the lead in this area, and I think we need to do some work to regain that authority, that moral authority, that credibility with African American communities, with people with mental illness, communities that felt that they have been more on the end of getting the unwanted sedations, for example."

Freeman said the next steps are to reopen cases where deaths were attributed to excited delirium.

Freeman, an associate professor of forensic medicine and epidemiology at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, said there's some concern law enforcement may find new alternative explanations for deaths that appear to be caused by excessive use of force, like drug use, but the science on excited delirium is settled and "we need to move on."

"It's a myth that is not going to be resurrected," he said.

Contributing: Katie Wedell and Cara Kelly, USA TODAY; Alessandro Marazzi Sassoon, FLORIDA TODAY; The Associated Press

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: What is excited delirium? Why California banned the disputed diagnosis