Affirmative Action Is In Danger, Again

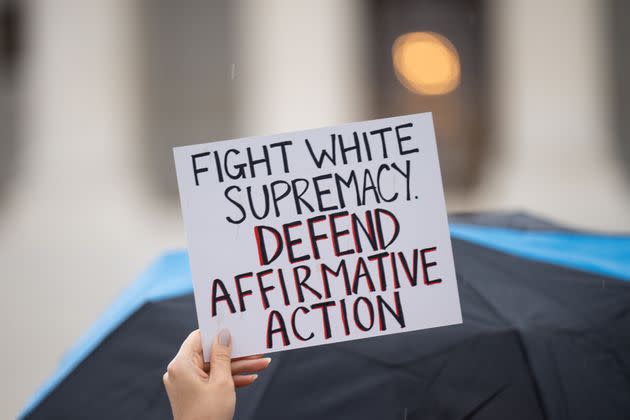

Protesters gather in front of the U.S. Supreme Court as affirmative action cases involving Harvard and the University of North Carolina admissions are heard on Oct. 31, 2022.

Barbara Grutter, a white lady from Michigan, filed suit when she was rejected by the University of Michigan Law School, which admitted that it took steps to ensure a racially diverse student body. In Grutter v. Bollinger, a landmark case on affirmative action that caught national attention in 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court determined the law school’s admissions policies were not unconstitutional.

However, the companion case, Gratz v. Bollinger, saw a different ruling: The Supreme Court deemed Michigan’s undergraduate affirmative action process — in which an automatic 20 extra points were given to Blacks, Latinos and Native Americans on a 150-point admission scale — unconstitutional.

I was in my senior year at Michigan in 2003, and I remember all the eyes on us. As I was wrapping up an enriching and life-changing scholastic career at the university, I’d hoped against hope that the high court — and the rest of the world — saw the value in having more people who looked like me matriculate at such a prestigious university.

Two decades later, we’re back at it as bored septuagenarian Edward Blum continues his tireless crusade toward keeping universities as white as possible with not one but two lawsuits by his nonprofit Students for Fair Admissionsagainst the University of North Carolina and Harvard University.

Perhaps the most visible and vocal plaintiff in these cases is Jon Wang, a Chinese American teenager who believes he was rejected by Harvard and five other top universities despite stellar grades and a 1590 SAT score because of affirmative action.

However, one of those six schools, the University of California, Berkeley, cannot employ race-based affirmative actionin its admissions policies, making Wang one of the many qualified applicants who simply didn’t get in.

Considering we have the most conservative Supreme Court in generations, no one is optimistic about the future of affirmative action as a means of diversifying American universities. Justice Clarence Thomas, who has been engaged in a personal battle against affirmative action despite benefiting from it as a highly successful Black man born in the 1940s South, will almost certainly disappoint the ancestors (once again) by voting against it later this month.

My personal experiences may seem inconsequential in the grand scheme of the affirmative action discussion, but, while whole books have been written about affirmative action in scope, not enough ink has been spilled about what diversity, or lack of it, feels like.

The University of Michigan had a roughly 6% Black student population when I started attending in 1999. At a bit under 50,000 students, that’s roughly 3,000 Black folks — less than the population of my entire high school.

We kept things tight — there was never more than a degree of separation between any Black student — because culture dictated that we do so. Our parties were policed harder than others’ and we leaned hard on each other, as well as the university’s Black support staff, to make it to caps and gowns at one of the most challenging state universities in the country.

We had our Black homecomings, our Black graduation ceremonies, a Black Student Union and even “Black dorms” (word to Markley Hall in the mid-1990s). I’m a core member of a Black male support group that exists to this day; I remain connected to current students after 20 years away.

I couldn’t give you exact numbers, but most of the Black folks with whom I attended Michigan are unqualified winners in life. Even in my immediate crew of close Black male friends, I’m the only liberal arts chump among engineers and a medical doctor.

There’s a good chance a lot of us wouldn’t have even made it to Michigan without affirmative action.

My high school GPA wasn’t mind-blowing. But my ACT score was decent, I wrote a damn good essay for my application and I attended a selective enrollment Detroit public school with a 90-plus-percent Black student population that fed to the University of Michigan — at some other school with the same grades, I might not have been accepted.

Considering it’s a state institution a half-hour drive from Detroit, one of the Blackest major U.S. cities, Michigan recognized the importance of race-based admissions policies. But Gratz v. Bollinger made things harder for us: Michigan had only 4% Black enrollment in 2021 — a one-third drop from my time there.

When I visit the campus today, I can feel the change: The spaces we carved out for ourselves have been either transformed or no longer exist. Testimonies from Black students from the last 15 years suggest that the university is simply ... whiter.

Richard Sander and Stuart Taylor Jr. argue in their piece “The Painful Truth About Affirmative Action” for The Atlantic that lower-performing minority students placed in high-performing environments are set up for failure, but I disagree: Michigan didn’t accept the scrubs skipping school four times a week to kick it at McDonald’s just because they were Black. The 20 points it added were for students who took care of business in high school … the valedictorians and folks active in extracurriculars.

Some beneficiaries of affirmative action did flame out of Michigan, but so did many of the white students who made it in — depending on your major, the university can be brutally difficult, and the work requires discipline regardless of how you got admitted.

Few opponents of affirmative action account for the positive effects a diverse student body has on everyone: Nothing bad will come of exposing students and staff to multiculturality on a collegiate level. To that end, the abolition of affirmative action in schools could also have a detrimental effect on the job market as it pertains to corporate diversity programs and the fact that businesses could again suffer the consequences of having C-suites that resemble a frat from “Animal House.”

Harvard has admitted that there’s no more efficient means of diversifying its student population than affirmative action policies; if the Supreme Court ruling goes badly, hopefully, universities can get creative and backdoor their ways into affirmative action.

Black matriculation and graduation from four-year universities remain frustratingly lower than for any other ethnicity, and data suggests that white women (who tend to push back against affirmative action) have historically been affirmative action’s biggest beneficiary.

The sad irony is that many right-wing Black folks and other underrepresented minorities love to suggest that racism is all gone because … hey, they worked really hard and became winners without handouts! A very notable exception is Colin Powell, who became the first Black secretary of state following a storied military career that began in a U.S. Army that had just been desegregated.

Powell was a Republican, and he wasn’t exactly loud on behalf of Black folks, but even he recognized the value of affirmative action.

I’ve always empathized with the classic affirmative action counterpoint: the idea that a white male can work hard his entire life to get accepted to a prestigious school, only to “lose” his spot to an underrepresented minority whose grades weren’t as good as his.

However, as is the case with Wang, one cannot prove that affirmative action is the explicit reason they aren’t accepted to one or several schools that weigh several factors to determine who gets in. Sometimes, you just get a bad break, and it’s easier to point the finger at Black and brown folks.

Also, to understand socioeconomic and ethnic disadvantages is to realize why two candidates with different ethnicities and high school scores might be more comparable than what we see on paper. Since I’m sure Black Americans will be given the runaround for reparations until our great-grandkids are pushing daisies, I’ll take whatever academic bonuses we can get — especially when applied to someone who will do them justice.

If you don’t view this as a greater social good, then chances are you feel like your “spot” in society is in danger. Or perhaps you’re simply a delusional “I get mine out the mud” ethnic minority.

If you fit in either category, I encourage you to read a book or three.