What Was Affirmative Action Really About? And What Happens Now?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Universities can no longer consider race in college admissions, the Supreme Court ruled today. The ruling was expected, on 6-3 ideological lines, and it will forever change access to higher education in America. Like it or not, “affirmative action” was extraordinarily effective — in its first year at Harvard, admissions of Black students rose 51 percent, and diversity on college campuses has increased in every decade from the 1980s to the 2020s.

And now, it’s over.

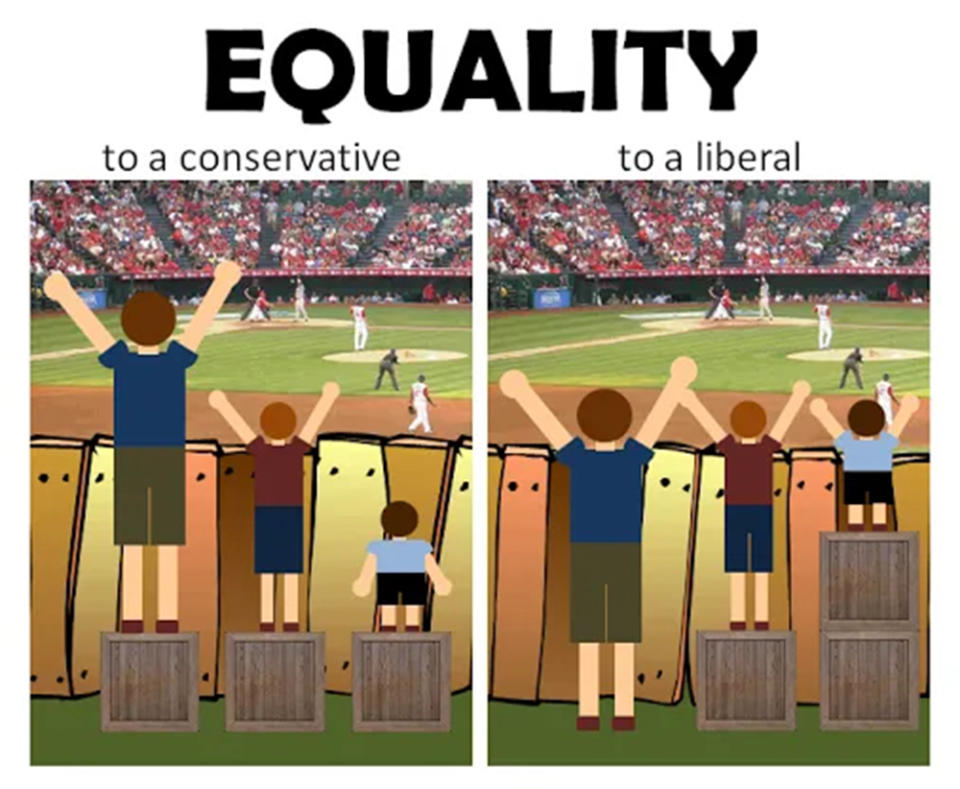

What happens next? In many ways, the answer to that question is based on what affirmative action was really about in the first place. And that question is well summarized in this 2012 meme created by a professor at the University of Cincinnati business school. It’s morphed many times over the last decade, but this is the original form:

You can see the difference, right? In the conservative view, everyone is treated equally, without regard to height. But because there are existing disparities — in the meme, it’s height; in life, it’s the countless ongoing disparities due to the legacies of slavery, Jim Crow, redlining, and other aspects of systemic racism — the shorter person can’t see the game. So is that really equality?

To a liberal — or, I would say, to someone basing their views on the reality of history and economics in America — equality means that everyone has the same opportunity. Not that they’re all treated the same, but that they can have the same chance to watch the baseball game.

This exact debate played out in today’s Supreme Court’s opinion.

Chief Justice Roberts clearly espouses the “conservative” view. He says plainly that education “must be made available to all on equal terms.” All racial discrimination is the same, and is equally forbidden by the Constitution. In other words, the Constitution must be “color-blind,” a term Justice Clarence Thomas uses dozens of times in his concurring opinion. Equality means that race (or height, in the metaphor of the meme) is never taken into account.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s dissents espouse the “liberal” view. Yes, sometimes race has to be taken into account, because that’s the only way to remedy the structural advantages that white people still have, on average, over Black people. Affirmative action — giving Black applicants to college some kind of “plus” that white applicants don’t get — is like that extra crate that the shorter person gets to stand on.

There is simply no agreement, on the Supreme Court or in our society, about which view of America and our Constitution is correct.

To his credit, Roberts spends several pages of his opinion describing how America, and the Supreme Court in particular, perpetuated racism in the century after the Civil War. No joke, his opinion would almost certainly be banned by a Florida public school, since it capably describes the many structures of racism in our country — at least through the 1960s.

But, by the end of his opinion, Roberts says it doesn’t matter. He writes that while the liberal justices who dissented “would certainly not permit university programs that discriminated against black and Latino applicants, [they are] perfectly willing to let the programs here continue … Separate but equal is ‘inherently unequal,’ said Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka. It depends, says the dissent.”

Well, yes, Chief Justice Roberts. That’s exactly the point.

In America, racism is not a two-way street. Sure, an individual can hold anti-Black, anti-white, anti-Asian, anti-anyone views. But as a society, only some kinds of racism are reinforced by a system and a history that date back to the “original sin” of America, namely slavery. There’s no systemic racism against white people. White people weren’t harmed by school segregation, Jim Crow, redlining, different access to economic opportunities after World War II, and so on.

So, yes, of course it depends which way the race preference is pointing. If it’s remedying inequality of opportunity, that is different from perpetuating it.

To be clear, Justice Roberts’ view has two very strong points in its favor — corresponding to two major flaws in that meme.

First, the 14th Amendment to the Constitution does not talk about systems; it talks about individuals. The equal-protection clause says that the state may not “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” On its face, when the crate is taken away from the tall person at the baseball game, he is definitely not receiving equal protection. And unlike in the meme, at Harvard, he doesn’t get partially admitted — he gets rejected. For this reason, the Supreme Court has developed a very strict test for when race can be taken into account, and most of the Court’s opinion is devoted to showing why the Harvard and UNC affirmative action policies fail it.

Second, there’s long been confusion about what, exactly, affirmative action is meant to do.

In the baseball meme, the crate is there to give everyone equal opportunity. It benefits the short person. And in the first 10 years of affirmative action, that’s what it did in colleges. It was an affirmative action designed to level the playing field. Indeed, even today’s opinion leaves open the possibility of affirmative action if an individual has been harmed by racial discrimination.

In the last 40 years, though, that rationale has been muddied. Affirmative action became about diversity, not remedy. That may be a “compelling state interest,” in the legal formulation, but it’s also hard to measure, and hard to say why using a race-based category is the best way to go about it. Does admitting an upper-class Black student from a tony suburb really provide “diversity” more than, say, a disadvantaged rural white, Hispanic, or Asian one?

Not only is diversity hard to measure, but it also offends basic American values of fairness. A conservative might not agree with the baseball meme, but they can still appreciate that giving the shorter person a crate to stand on seems fair. It’s a lot harder — not impossible, but harder — to explain this in the context of fostering diversity on a college campus. This is one reason why affirmative action is so broadly unpopular — even a majority of Black Americans don’t support it.

This is also why it failed at the Supreme Court. “Although these are commendable goals,” writes Chief Justice Roberts of diversity, “they are not sufficiently coherent” to be constitutional. “Harvard’s admissions process rests on the pernicious stereotype that ‘a black student can usually bring something that a white person cannot offer.’”

The baseball meme also oversimplifies the reality of a multiracial democracy. It’s not just two or three groups affected. One of the lead plaintiffs in the Supreme Court case was a consortium of Asian American organizations that claimed that de facto racial quotas were hurting Asian students most of all.

Were affirmative action really like the baseball meme, it might have survived. Justices Sotomayor and Jackson recognize as much, pivoting back to the original, remedial purpose of affirmative action and the incontestable reality of persistent racism today. But the Harvard and UNC systems were not like that. They were for diversity, not remedy, and they directly harmed individuals as a result.

So what now?

The Court’s opinion is not Ron DeSantis’ dystopian nightmare where no one can talk about race or racism. As Roberts explicitly says, college applicants can still talk about how they faced challenges based on racism (or anything else) and universities can still take that into account. They just can’t make race, itself, a bonus that can help an applicant’s chances.

Universities have also already indicated that they intend to take income level into account, which unlike race is not a characteristic protected by the 14th Amendment.

That being said, this is a major change both in constitutional law and, I think, in how America understands racism. The Supreme Court has staked out a strong claim for the “conservative” view of equality: that discrimination against any individual is prohibited by the Constitution, and that the existence of systemic racism does not justify it.

In an ideal world, the end of affirmative action for university admissions should spawn serious public investment in the other manifestations of systemic racism, such as underfunded and underperforming schools and disparate health outcomes for Black Americans. These and many other factors are the root causes for why Black college applicants tend to have lower test scores, on average, than white and Asian applicants — and they must be ended.

But wasn’t the whole point of affirmative action that we don’t live in that ideal world? And that until we do, we need to use a lesser evil (taking race into account) to fight a greater one (systemic racism).

Maybe that was the point, and maybe that’s why six conservative justices voted to strike it down.

More from Rolling Stone

Group Uses Supreme Court's Own Words to Challenge Harvard's Legacy Admissions

AOC: Supreme Court Rulings Show 'Creep Towards Authoritarianism'

Michael Imperioli Bans 'Bigots' From Watching 'The Sopranos': 'Thank You Supreme Court'

Best of Rolling Stone