Afghans who fought in secret CIA-trained force face legal limbo

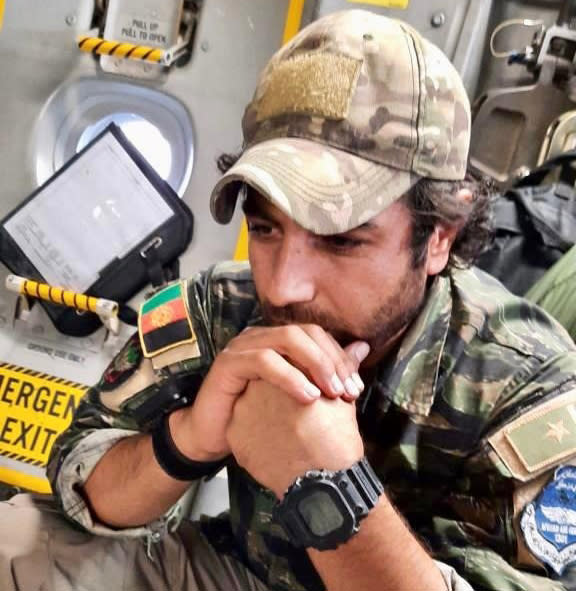

Thousands of Afghans who fought under the command of the CIA for years and provided security for American intelligence officers say they face a debilitating legal limbo in the U.S. and are appealing to Congress and the Biden administration for help.

About 10,000 to 12,000 members of the Afghan National Strike Unit, a clandestine force known as the “Zero Units,” were evacuated from Afghanistan when the U.S. military withdrew from the country in August 2021. But their two-year work permits in the U.S. are due to expire within days or weeks, and the veterans worry they will no longer be able to support their families — and some worry the work they did for the CIA may even be harming their chances of getting green cards.

A former Afghan commander with the strike force, Gen. Mohammad Shah, wrote a letter warning lawmakers last month that his former troops are in “urgent crisis” and pleading for action to resolve their status.

“Without your help, we are trapped,” Shah wrote in the letter, which was obtained by NBC News.

“Recently, there have been cases of suicide within our community driven by the overwhelming sentiment of helplessness we feel as our requests for immigration assistance go ignored by the U.S. Government,” Shah wrote.

Nasir Andar, a veteran of the force, said his comrades are struggling with depression as the clock ticks on their work permits.

“Some of them are feeling hopeless. They don’t know what to do,” said Andar, who is the chief of community engagement at a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping the veterans. “We are trying to guide them and boost their morale.”

At least two veterans from the CIA-trained force have taken their lives since arriving in the U.S., according to Andar and other advocates at FAMIL, the nonprofit trying to help the veterans.

Since they arrived in the U.S. two years ago, most of the veterans of the force have not received special immigrant U.S. visas — which were created for Afghans and Iraqis who worked for the U.S. government. Without those visas, the veterans cannot apply for green cards, leaving them in a legal gray zone.

The veterans were “promised” proper legal status “in consideration for our service to the U.S. government on the battlefield,” Shah wrote in his letter.

A spokesperson for U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services said the administration recently announced a streamlined process that will allow Afghan refugees to apply to renew their temporary legal status for two more years and continue to work in the U.S. while they apply for permanent legal residence.

“This action is part of the Biden-Harris Administration’s ongoing commitment to the safety, security, and well-being of the thousands of Afghan nationals who arrived in the United States” after the U.S. exit from Afghanistan, the spokesperson said.

The renewal requests “will be considered on a case-by-case basis for urgent humanitarian reasons and for a significant public benefit,” the spokesperson added.

But advocates for the Afghan veterans say that the bureaucratic process has proven frustrating and that standard questions for green card applications do not take into account their unusual circumstances as CIA-trained operators. The applications include questions like: “Have you EVER received any type of military, paramilitary, or weapons training?”

When Afghan Zero Unit veterans have answered yes to that and similar questions, their applications do not seem to advance, advocates said.

“We’re not asking for special treatment for these families. What we’re advocating for is a matter of basic humanity,” said Geeta Bakshi, a former CIA officer who worked with the National Strike Unit in Afghanistan.

“These are men and women who risked their lives on a daily basis to protect Americans during a 20-year war that a lot of Americans have forgotten about,” said Bakshi, who created FAMIL to help her former Afghan colleagues. “These are veterans who should be celebrated in America. I could never have imagined that they’d be so disadvantaged by our bureaucratic processes.”

Advocates for the Zero Unit veterans say they were heavily vetted before they joined the force for any possible terrorism links and regularly underwent security checks, a level of screening that interpreters for the U.S. military or other Afghan employees were not subjected to. In the entire 20-year war, members of the Zero Units never launched an attack on their U.S. advisers. Such “green-on-blue” attacks against Americans became frequent occurrences among Afghan recruits to the army and the police force.

The Zero Units, trained and overseen by the CIA, operated under a veil of secrecy during the war, conducting combat operations and securing intelligence outposts. Even now, U.S. officials cannot explicitly acknowledge the connection between the intelligence agency and the paramilitary force as it remains classified.

The force played a crucial role in the U.S.-led effort to weaken Al Qaeda after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and as its troop presence scaled back, the U.S. increasingly relied on the Zero Units to safeguard U.S. and coalition personnel, including at Kabul airport in the final days of the 20-year U.S. presence, former CIA officers said.

“These were the guys that did a lot of heavy lifting, but their role really isn’t too well known or understood,” said a former CIA officer with experience in Afghanistan. “It was all done with discretion built in.”

The Zero Units also have faced scrutiny over their operations, with human rights organizations alleging the troops committed abuses and possible war crimes, including extrajudicial executions and attacks on medical facilities.

Afghan veterans of the force and former CIA officers who worked with them reject the allegations, saying that the Zero Units were trained in the laws of armed conflict and that each operation was carefully vetted beforehand. But some former CIA officers worry that the allegations of abuses could undermine or delay efforts to resolve the legal status of the Afghan veterans.

“The CIA and its Afghan partners, unlike other forces in country, went to great lengths to avoid civilian casualties,” said a former U.S. intelligence officer.

The CIA spokesperson said the U.S. takes claims of human rights abuses “very seriously” and undertakes “extraordinary measures, beyond the minimum legal requirements to reduce civilian casualties in armed conflict and strengthen accountability for the actions of partners.”

The spokesperson said that “a false narrative exists about these forces that has persisted over the years due to a systemic propaganda campaign by the Taliban.”

A former member of the Afghan force said the National Strike Unit operated directly under the CIA’s command at all times and was not carrying out rogue operations.

“We were taking every order from them. We did not shoot a single round without their permission,” the Afghan veteran said.

The CIA has advocated for the Afghan veterans in discussions with the Citizenship and Immigration Services and other federal agencies, and some lawmakers have championed their cause.

A CIA spokesperson said that the U.S. made a commitment to the Afghan veterans to create a pathway to citizenship and that the “process will take time, but we never forget our partners and are committed to helping those who assisted us.”

The spokesperson added, “We are continuing to work closely with the State Department and other U.S. government agencies on this effort.”

The State Department declined to comment.

Rep. Mike Waltz, R-Fla., a member of the Intelligence, Armed Services and Foreign Affairs committees, said that “if anybody deserves to be here, it’s the Afghans who stood alongside us against terrorism.”

Waltz, a former Army Green Beret who served in Afghanistan, added, “The administration should settle their status.”

In the meantime, many of the Afghans from the Zero Units are feeling abandoned by the government they risked their lives for.

“What we were promised, the things that we have done for this country … we weren’t expecting this,” one Zero Units veteran said.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com