The African president’s daughter adopted by a North Korean dictator

In a brilliant 2008 comedy sketch, David Mitchell and Robert Webb played a pair of SS soldiers noticing that their hats were decorated with skulls and beginning to suspect they might be “the baddies”. In 1989, Monica Macias experienced that unpleasant sensation for real, while at university in North Korea. Long taught to consider president Kim Il-sung as a God-like power, she was appalled to see a visiting Syrian student casually sit down on a newspaper with the Great Leader’s face printed on its front page. When she told him to get up, he just laughed at her unquestioning devotion to authority and sighed that a girl brainwashed by the North Korean regime would never be able to think independently.

But Macias proved him wrong. Despite the temptation we all feel to cling to long-held world views, she began to challenge what she had been taught and, “saw fences in my mind that until then had been invisible to me”. And her extraordinary memoir, Black Girl from Pyonyang, asks Western readers to start asking themselves similar questions. Because – having lived in Africa, America and Europe since leaving Pyongyang in 1990 – Macias thinks we’re all equally guilty of making oversimplified assumptions that we’re the goodies.

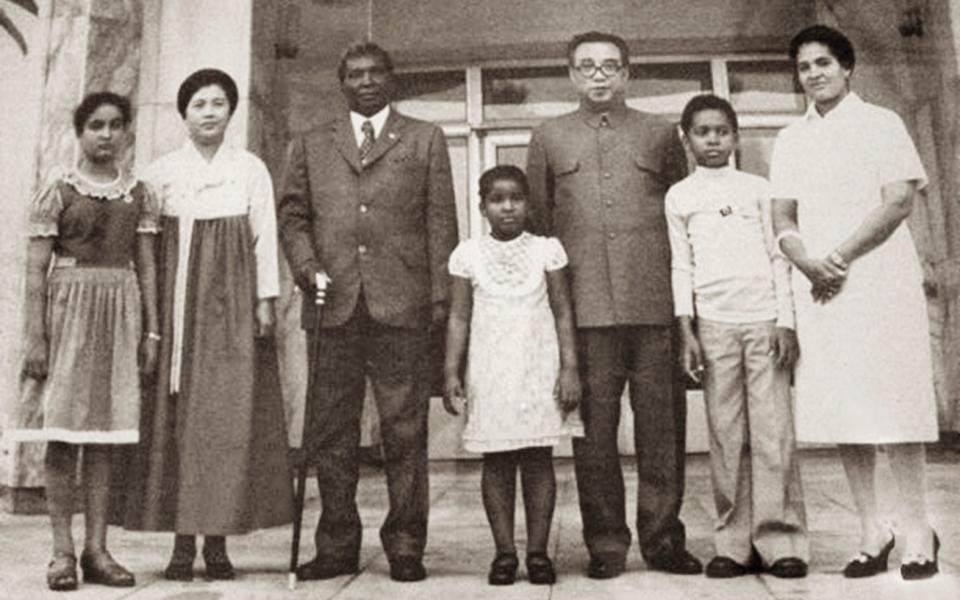

Her “unusual” life story certainly gives her a unique vantage point from which to comment on global divisions. For Macias (who currently lives in London and works in a clothes shop) was born in 1971, the fourth child of the first legitimate president of independent Equatorial Guinea, Francois Macias. Fearing for her safety and seeking to strengthen his country’s ties with the communist bloc, he sent her to be raised in North Korea by the man she calls her “adoptive father”: Kim Il-sung. Shortly after she arrived in Pyongyang, aged eight, her father was accused of perpetrating atrocities and executed by firing squad – although nobody told her he was dead.

Feeling abandoned by her family, the young Monica struggled to fit into Korean society. At first she rebelled against its military discipline but eventually chose Korean culture over her own. Her Great Leader had promised her father that he would educate her and send her home to serve her own country. So he employed a Spanish teacher to ensure she kept up with her native language, but she refused to learn it and cleaved ever closer to Kim’s dictatorial regime, until the incident with the Syrian student and the newspaper.

After that, Macias resolved to quit her “sheltered, counterfeit existence” in Pyongyang and visit her maternal grandfather’s country, Spain. “Are you strong enough to live in that harsh capitalist world?” Kim Il-sung asked her. She felt she was. But she was in for a series of destabilising perspective flips as she began travelling the world. In Spain (where she worked as a nanny) she loved the sexual freedom but struggled with the racism. In China she finally spent time with Americans and South Koreans and realised they were not “evil” as she had been taught. But a visit to Seoul taught her that South Koreans were just as blind to the humanity of those in the North as her Northern friends were to that of those in the South. In New York (where she designed and sold jewellery) she was depressed by the American obsession with money and began to suspect that capitalism built just as many “fences in the mind” as communism. In America people struggled to pay for basic medical treatment, while a visit to Equatorial Guinea taught her that African superstition put up equal barriers to life-saving care. Her experiences made her question “whether any nation has earned the moral authority to lecture others.”

London initially offered Macias a good balance of the American individualism she admired with a more Asian-style commitment to good manners. Having been nicknamed a “sheep” (for her African hair) in Korea and been on the receiving end of much more abusive racism in Spain she was delighted to find that people could identify as “black British” on job applications in the UK. “That might not strike native inhabitants as unusual,” she writes, “but it was both revolutionary and pleasing to me… It seemed you could succeed in London no matter your origins.” Alas, a stint as a maid at a Park Land hotel taught her that a woman with brown skin and mop in hand would not be granted the respect she had expected.

Along the way she tried to tell her story and reconcile her personal experience of Francois Macias and Kim Il-sung as kindly men with their Western reputation as brutal dictators. In Spain, she met with one of her father’s former advisors who told her that her father was a decent man – although they had parted company when her father insisted on making himself president for life. In London, Macias began a thorough investigation of her father’s regime for a Masters Degree in International Studies and Diplomacy at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London. She claims she was determined to find the truth at all costs. She interviewed 3,000 witnesses to his regime and concluded that he was not directly responsible for the “heinous” crimes committed during his tenure. She argued that if he had embezzled funds, her mother would not have ended up selling plantains for a living, nor would she have been scrubbing toilets. Though readers can draw their own conclusions, she’s certainly right to point out that it was in neither the interests of her father’s deposers nor the ousted Spanish colonists to defend his honour.

She also continues to defend Kim Il-sung (whose human rights record is condemned as “catastrophic” by Amnesty), arguing that life in North Korea was pretty good before the famines of the early 1990s, and quoting from defectors who now regret leaving for the South and wish to return. Yet she doesn’t really acknowledge that her own experience of Pyongyang was highly privileged and not reflective of the general population. For one thing: she was free to leave as the food ran out.

But you don’t have to buy all of Macias’s conclusions to admire her attitude. As social media algorithms herd us all into bubbles which “protect” us from the discomfort of differing worldviews, we could all learn a lot from her lifelong quest to challenge her own prejudices. She remains open minded and makes no claim to have access to absolute truths. We can apply her commitment to critical thinking on smaller scales too, always asking ourselves who has a vested interest in spinning which stories. We might still decide that some people really are the baddies. But we should all, constantly, be questioning the symbols on our own hats.

Black Girl from Pyongyang is published by Duckworth at £18.99. To order your copy call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books