Against all odds, she became Purdue's student president: 'I don't want people to pity me'

Shye Robinson desperately wishes she didn't remember that day, the day when the chaos inside her home came to a boiling point; the day she ran down the street in a panic, knocking on doors to call 9-1-1; the day she went back home and rode in an ambulance to the hospital with her mom lying on a gurney.

Unfortunately, Robinson said, she remembers that day vividly, unlike much of her life before that, which had been a hazy cloud.

But that day in 2013 is crystal clear. That was the day Robinson's mom lost custody of her. That was the day that would put her into the foster care system.

Robinson was 11 years old, at home with her 4-year-old sister when, suddenly, three adults walked into their Fort Wayne house, three people their mom had let inside, three people Robinson didn't recognize.

That was not particularly alarming, at first. Robinson was used to going on ride-alongs with her mom to seedy places she wasn't familiar with and meeting people she didn't know. But this felt different.

One of the adults inside her home that day was an overbearing woman, who seemed to be trying to distract Robinson and her sister. She kept talking to them, trying to keep them near her, trying to keep them occupied. It felt like that woman didn't want them to see what was going on in the other room.

In hindsight, Robinson knows now, at the age of 21, it was all drug-related, all connected to the fix her mom needed. She later found out those people were there to rob her mother and to kill her. All she knew at the time was she was terrified. She knew her mom needed help.

Robinson made up a story to that woman hovering around her, telling her she needed to go down the street to talk to a friend about going bowling. She ran out of the house, raced down the road and knocked on neighbors' doors until she found someone at home.

She frantically dialed 9-1-1 and told the operator she needed someone quickly. She needed someone to help her mother.

What happened after that turned back to the blur Robinson was used to. She can't remember exactly what happened next. She does remember the ambulance ride, going to the hospital to get her mom help.

And she does remember that was the day the Indiana Department of Child Services opened the case that put Robinson and her sister into the foster care system.

As Robinson told her story to IndyStar last week, she paused for a moment. She doesn't want to put her parents down or make them look bad, she said. They had their addictions and mental health struggles, but she knows they loved her very much.

"I get shy when people really talk about that. I don't want people to pity me," she said. "The outcome is good, you know?"

Yes, the outcome is good. The outcome is, actually, remarkable.

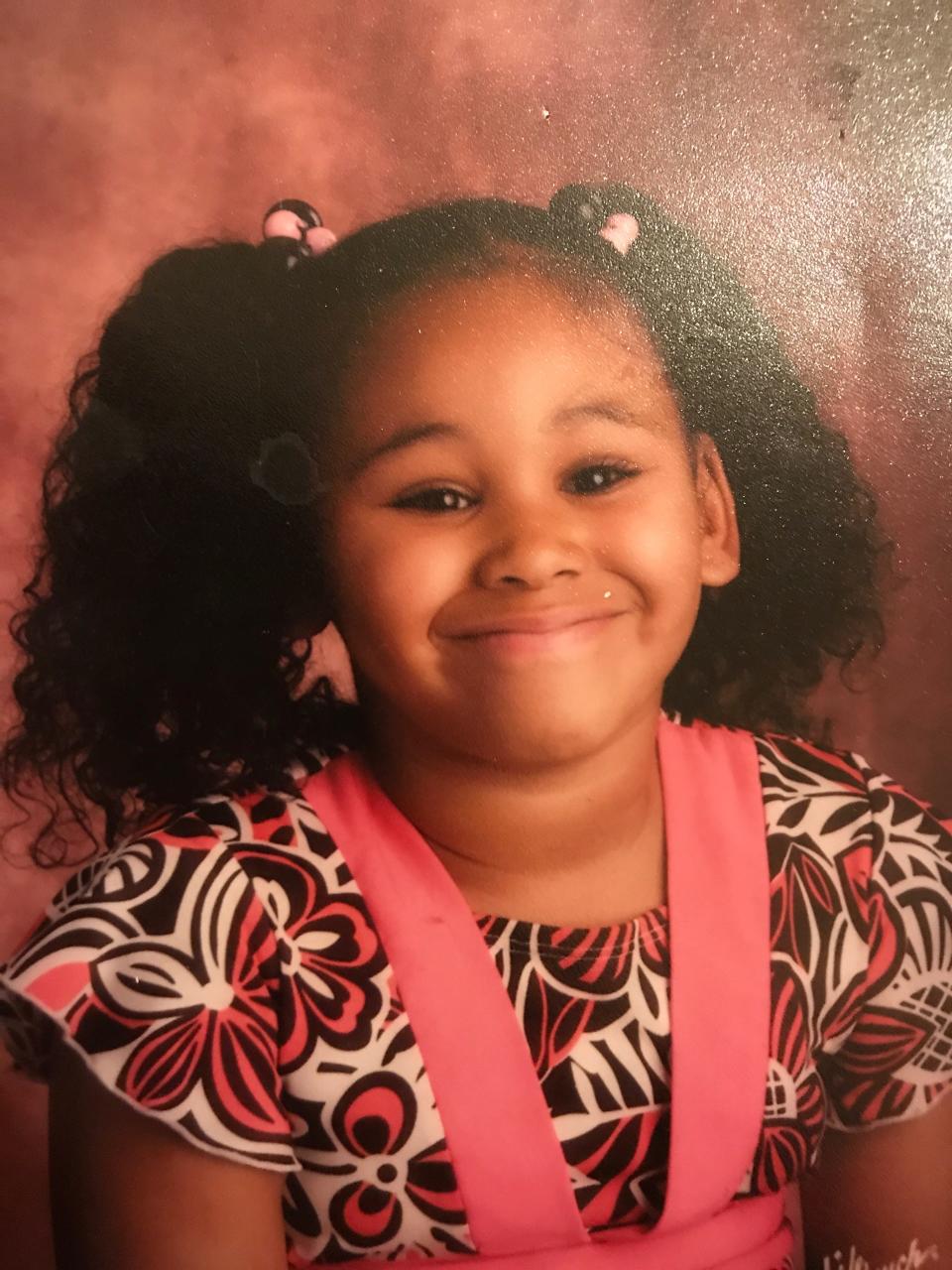

That scared 11-year-old girl, with her mom suddenly gone from her life, forged ahead. Robinson became salutatorian of her class at Northrop High in Fort Wayne. She was a member of the National Honor Society, was on the dance team, played soccer and ran track and won actor of the year, taking lead roles in school productions.

Robinson is now a senior at Purdue, a double major in political science and brain and behavioral science with a minor in Spanish, who has plans to apply to be a Rhodes Scholar. She also happens to be president of the Purdue University student body.

Against all odds, Robinson persevered, broke the cycle of drug addiction, found a stable home, two loving foster parents, two loving foster siblings and she came out on top.

“Shye is extraordinarily motivated not to live the life she saw in her biological family home," said Thea Strand, Robinson's case manager at Damar Services. "And I have zero doubt she will do that. She wants to be involved in making positive changes in the world. And she will."

'I tried my best to pretend I wasn't in foster care'

Robinson has never liked sharing her life story. Growing up, she tried her best to keep the fact she was in foster care a secret from every friend, every teacher, every classmate, every single person she crossed paths with.

"It's a very messy life story to talk about," Robinson said. "My parents suffered from drug addiction and drug involvement and just like a lot of illegal crime and I was the complete opposite of that."

Robinson was a really good student, a straight-A student, but she would have to miss school to go to her court hearings. She never wanted to go those hearings. She pleaded with anyone who would listen to not make her go. She was Black with two white foster parents. She knew people wondered about that.

"I avoided talking about my family to my peers. I don't think I ever admitted that I was a foster child willingly," she said. "I was very embarrassed. I tried my best to pretend that I wasn't in foster care. That's the best way I can put it."

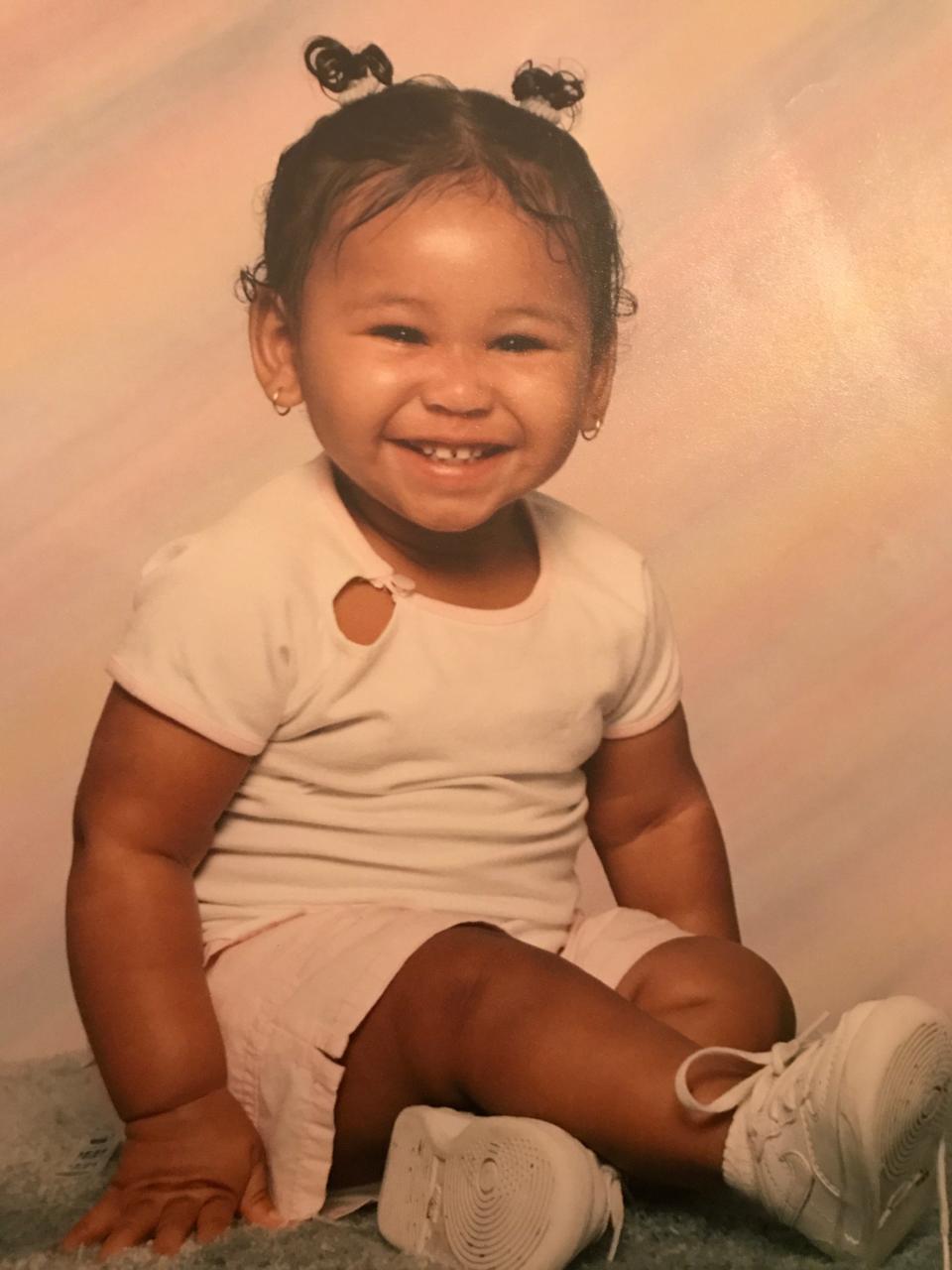

During the early years of her life, there was no foster care. Until she was 11, Robinson was raised by her mom, her grandmother and her dad when he wasn't in jail or living in another state. At some points in her life, Robinson's grandmother was her primary caregiver.

"She would call me her ride or die," said Robinson. "She would do anything for me. I felt special."

Robinson has many great memories with her biological family, even if she also has some awful ones. Her mother, when she wasn't reeling from addiction, always encouraged Robinson to do well in school, to make good grades. That was very important to her mother, who wanted something better for her daughter than she had.

Robinson's mother had dropped out of high school at 17 when she became pregnant with Robinson's older sister, who soon was taken away from her mom by a relative.

When her dad was around, he harped about making good grades, too. And he carried her on his shoulders. Robinson was always insecure as a child about her weight and how she looked.

"No matter how old I was or how much I weighed, he always would crouch down and tell me to get on his shoulders," Robinson said. "And he would carry me around and dance and it would be so much fun."

Sometimes, her dad would put on New Orleans bounce music, blasting it on the television, and the two would dance like crazy.

"My dad was a loving man. He always made the kids around him feel safe and protected, but also was not afraid to be goofy and playful," Robinson said. "This is one of the things that I will always be proud of when I talk about him. Those moments are when I felt the magnitude of his love."

But no matter how much her biological family loved her and wanted the best for her, they could not provide the stability Robinson needed. Sometimes, her mom would be "out of it" for days from the drugs. Sometimes, her dad was in jail. When Robinson was in middle school, he moved to Louisiana.

That left Robinson with her mother and her grandma. But when her grandma got cancer and died at the age of 42 in 2013, her mom went on a downward spiral she couldn't fight her way out of. And the turmoil began.

'She finally had stability'

Two years before her grandma died, Robinson and her family moved into a new neighborhood in Fort Wayne. Shannon Roberts lived two houses down the street. Most of the neighbors, including Roberts, knew there was chaos in the Robinson house.

Roberts and her then-husband Chris tried to provide a safe, welcoming space for Robinson, who was 9 at the time. That summer of 2011, Robinson came to the Roberts' house almost every day to hang out with the Roberts' children, Chloe and Cody.

The neighborhood was filled mostly with boys, so Robinson and Chloe became comrades. And the Roberts became trusted adults for Robinson. As school started in the fall, the Roberts made sure they had a bed for Robinson, and she stayed most weekends with them.

Shannon Roberts got to know Robinson's grandmother but knew little about her mom, who stayed inside most of the time. Robinson told Roberts her mother had health problems.

"But then things, they started to deteriorate for her family," said Roberts. "We didn't realize how much. But when her grandma passed away, we knew there was going to be a greater need. We didn't realize until DCS stepped in just how big of a need."

At first, Robinson and her sister were sent to live with their aunt. During those months, Chris and Shannon Roberts started the process of becoming foster parents. They had always wanted to have more children, but time had gotten away from them.

When Robinson's aunt, who had children of her own, said she could no longer foster her nieces, the Roberts were already licensed with the state to be foster parents.

"Shye had been in our lives so much by that time, it was just a natural and easy step to say she can live with us," Roberts said. Her little sister came to live with them, too. "I had no idea they would become our first and only foster children."

The early years were a bit of a struggle for Robinson. "It was really bad because she didn't always know she was safe," Roberts said. "She didn't always know what the future was going to hold."

There were always the court hearings, Robinson's mother trying to get her back, her father trying to get her to move to Louisiana to live with him. "It was a lot of uncertainty," Roberts said. "It took its toll mentally and physically."

The Roberts made sure Robinson was in therapy, and they kept reassuring her she was safe with them. They weren't going anywhere.

"Even though her life was in utter chaos and out of control from a foster child's perspective, she knew we would be there for her," said Roberts. "She finally had stability."

And Robinson finally began to blossom, finding great success academically and in her extracurricular activities. She became more confident. She knew what she wanted in life and what she didn't want.

And, sometimes, that meant making really tough decisions that tore at her soul.

'Didn't want to put a knife through her mother's heart'

As Robinson lived with her foster parents, there were points when she still had visitations with her biological mom and dad. There were points in her life when her mom fought to get Robinson and her sister back.

But Robinson didn't want to go back with her mom, and she stood up in court rooms and advocated for that. "At the time, I really didn't trust her to still be a good parent," Robinson said. "I was concerned about that."

At the same time, the Roberts wanted to adopt her, but Robinson didn't want that either, not because they weren't wonderful foster parents, but because she was fearful that would put her mom "in an even worse mental state."

Her mom had voiced concerns to Robinson, telling her, "I love you. You are my child." Robinson knew if she were adopted that wouldn't change how much she loved her mom or that fact she was her daughter.

"But she didn't want to put a knife through her mother's heart," said Strand.

Shannon Roberts said she understood. She and Chris really wanted to adopt Robinson, but ultimately, they let her make that choice. "It was just so clear she had such an identity already; she was not ready to rock that boat."

Despite all the struggles her mom's drug addiction caused her, Robinson is empathetic. She wants people to understand that drug addiction is a mental illness. The drugs altered her mom's physiological state.

"I'm proud of my mom now. She's gone through so much change and she's going to therapy," Robinson said. "She's been diagnosed with some mental illnesses and she's getting help with that."

But from an early age, Robinson knew she never wanted to be in that dark place her mother was in.

"I turned to school as an outlet because of my home life and because of the complications there," Robinson said. "Seeing the trauma and the unhealed trauma from my parents and how it drastically changed their lives, I was embarrassed, and I didn't want to be like that."

In 2018, when she was a sophomore in high school, Robinson's father died. She was distraught as she went to New Orleans for his funeral. It was an extremely difficult time. Robinson felt bad she had not moved to live with her father when he asked her to. But she was thriving in high school, and she had to prioritize. "I went through a lot, because I had resented my dad for a long period of my life," she said. "When he passed away, I had to really grapple with the fact that I couldn't get closure and I couldn't really effectively communicate to him ever again that I really did love him."

But despite the sadness and grief, Robinson forged ahead again. She graduated from high school as salutatorian, and then a new ally came into her life, a case worker named Thea Strand.

'She's a delight and joy'

It was Aug. 28, 2020, months after Robinson graduated from high school, when Strand made the first call. It was Robinson's 18th birthday and at 12:01 a.m. on their 18th birthday, foster kids are "released into the wild," Strand said. They no longer receive DCS funding.

Strand called Robinson and introduced herself as a case manager in DCS' older youth services program, which in Robinson's area is provided by Damar Services. Because Robinson was not going to be unified with her biological parents and because she had not been adopted, she qualified for the program, which is designed to help youth transition to adulthood.

As part of the services, Strand helps young adults with budgeting, grocery shopping, problem solving, job interviews, college applications and overall life coaching.

But with Robinson, it was different, Strand said. She had adulthood written all over her. She had her life together. She was headed to Purdue as a 21st Century Scholar.

"Shye is very different than many of our clients but part of that, to be quite honest, is she has had a very stable foster situation, whereas with most of our clients that is not the case," Strand said. "They've been here, there and everywhere. That said, it doesn't mean Shye has had any less anxiety and worry than any other foster youth."

From that first phone call between Strand and Robinson, they have talked or seen each other every week or every other week for three years.

"She's a delight and a joy. She's extraordinarily motivated and driven to succeed," said Strand. "And I'm talking about success on a lot of different levels, personally and professionally."

Robinson has always taken more classes at Purdue than she needs to graduate. She has applied for every extra opportunity that Purdue has offered her. She studied in Argentina, raising her own money for the semester abroad, with the Damar Foundation paying the rest. She went to Washington, D.C., last semester with the help from Damar.

"She has always known that we've got her back," said Strand, "and that she shouldn't say no to an opportunity because of the financial burden."

Robinson, who was admitted to Purdue as a biochemistry major, soon switched to political science. She has a passion for making changes in the world. Her junior year, she served as a senator of the student body.

Beth McCuskey, vice provost of student life at Purdue, met Robinson in the fall of 2022 when she hosted a dinner for student senators with her senior team of vice provosts. After a quick round of introductions, the students were encouraged to talk about whatever was on their mind and to ask questions.

"There were 30 people in the room, and I just remember Shye effervescing to the top in this space," McCuskey said. "How she was asking questions, the depth of what she was asking? She just has leader written all over her in so many ways. It was just fascinating."

Not long after that dinner, McCuskey learned Robinson had been in the foster care system and was the child of a drug-addicted mother. "I just recall being totally, totally blown away."

'No doubt, she is a rising star'

Purdue student Brayden Johnson was blown away, too, by the aura of Robinson. She was magnetic and a powerful force and he had an idea for Robinson. He sent her a message last semester asking for a lunch meeting.

The two met in the Purdue Memorial Union and he pitched his idea to Robinson. She should run for student body president. She had all the attributes. She was involved in campus life, she was involved in student government, and it seemed just about everyone on campus knew of "Shye."

"They want you to lead them," Robinson remembers Johnson telling her. A few days later, Robinson told Johnson she was in.

McCuskey moderated the student government presidential debate for 2023-24 and was again impressed by Robinson and running mate Andrew Askounis.

"She was so thoughtful, so charismatic," McCuskey said. "Just her presence, her ability to answer questions, there is just no doubt she is a rising star."

Robinson won the election, much to her disbelief. She said she had no idea she would actually win but, when she did, she went to work. As the Purdue student body president, Robinson is fighting to raise the undergraduate student minimum wage to $13.50. She knows that might not happen overnight, it might take incremental increases over time to get there, but she said it's vitally important.

"This ties into financial well-being and mental health. There are people who are making $7.25. There are people who are making $8, $9.50, and I think that that's not a sustainable wage," she said. “I feel financially secure. Because of my unfortunate circumstances, I have access to all of these benefits. It’s been traumatic. Everyone should have the feeling of financial wellness.”

As president, Robinson is also emphasizing Red Zone awareness. The Red Zone encompasses the months from when a student arrives on campus in the fall until they return home for Thanksgiving break. Those months are when more than 50% of all sexual assaults happen on college campuses nationwide. Robinson is advocating for education about the Red Zone and university response.

She is also a fierce fighter for diversity, not only in Purdue student government, but on campus. She plans to host a multicultural block party in the spring. "My biggest goal is always going to be advocacy," she said. "How can I be the best advocate?"

"Shye is a very ambitious and magnetic person. She can relate to anyone, which makes her one of the best networkers I know," said Johnson. "I am confident that when she puts her mind to something she will be able to talk to the right people to get it done. The student body may not attribute the changes on campus to Shye and her administration, but they will absolutely feel the effects of her hard work."

Robinson will one day be president of the United States. That's what her friends tell her. "They joke, 'I'm going to vote for you one day,'" she said.

Shannon Roberts isn't so sure that is a joke.

"She'll shake up the political world and I can't wait to see it happen because it's long overdue," said Roberts. "Shye is going to do great things. She is going to make waves. She is going to forge her path. You can only expect world changing things from her."

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Against all odds, Shye Robinson became Purdue's student body president