Ahead of This Year’s Elections, Over 50 Museums Commit to Feminist Art

In January of 2017, Apsara DiQuinzio was one of the 750,000 people who flocked to downtown Los Angeles for the Women’s March. The event made a lasting impression on the senior curator at the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, both for its grassroots nature and its collective impact; scrolling through the photos of marches held on all seven continents around the world, she was moved.

Womens March 2019

“The fact that it kind of organically sprung up everywhere was really incredible,” she explains. In the days that followed, DiQuinzio began to wonder if something could be done on a similar level within the art world, so she emailed a group of colleagues to bounce an idea off of them. Many emails later, the Feminist Art Coalition officially launched late last year as a yearlong initiative. Between September and November 2020, FAC will work with over 50 museums and institutions across the United States to present a series of events including exhibitions, performances, commissions, and symposia that use feminist thought as a springboard for greater civic engagement, discourse, and action.

The timeliness with election day 2020 is deliberate—like many people, DiQuinzio felt “caught off guard” following the evening of November 8, 2016. “But, more importantly, [the election] caught people off guard culturally.” It also dovetailed with the renewed momentum of the #MeToo movement, which helped to define misogyny on a national, if not international, level. Concurrently, the art world was beginning to have a larger reckoning with how it approached intersectionality and feminisms (the FAC refers to it in the plural, acknowledging the diverse range of approaches to gender parity). Like the rest of these discussions around representation and equality, this reckoning is ongoing: In November, for example, the Baltimore Museum of Art announced that it would spend 2020 only acquiring works by female-identifying artists.

Working with a range of institutions from the boutique to the behemoth (including Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, and New York’s Whitney Museum), FAC’s main goal is to continue these conversations by creating a “cultural support network” over the course of this year. This doesn’t mean that the focus will be exclusively all-female projects—rather, echoing the bell hooks adage that “feminism is for everybody,” the coalition hopes to foster a sense of inclusivity and diversity around feminist thought, both for institutions and visitors.

For many institutions, this intention organically aligned with upcoming programming already in the works. The Brooklyn Museum, which plans its exhibitions over a year in advance, is participating in FAC with an upcoming show, Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, which opens in November and continues through April 2021. Cocurated by Catherine Morris and Aruna D’Souza, the exhibit will be the first comprehensive retrospective of the conceptual artist whose plurality of work speaks to FAC’s belief in a plurality of feminisms.

The Whitney museum of American art in New York City

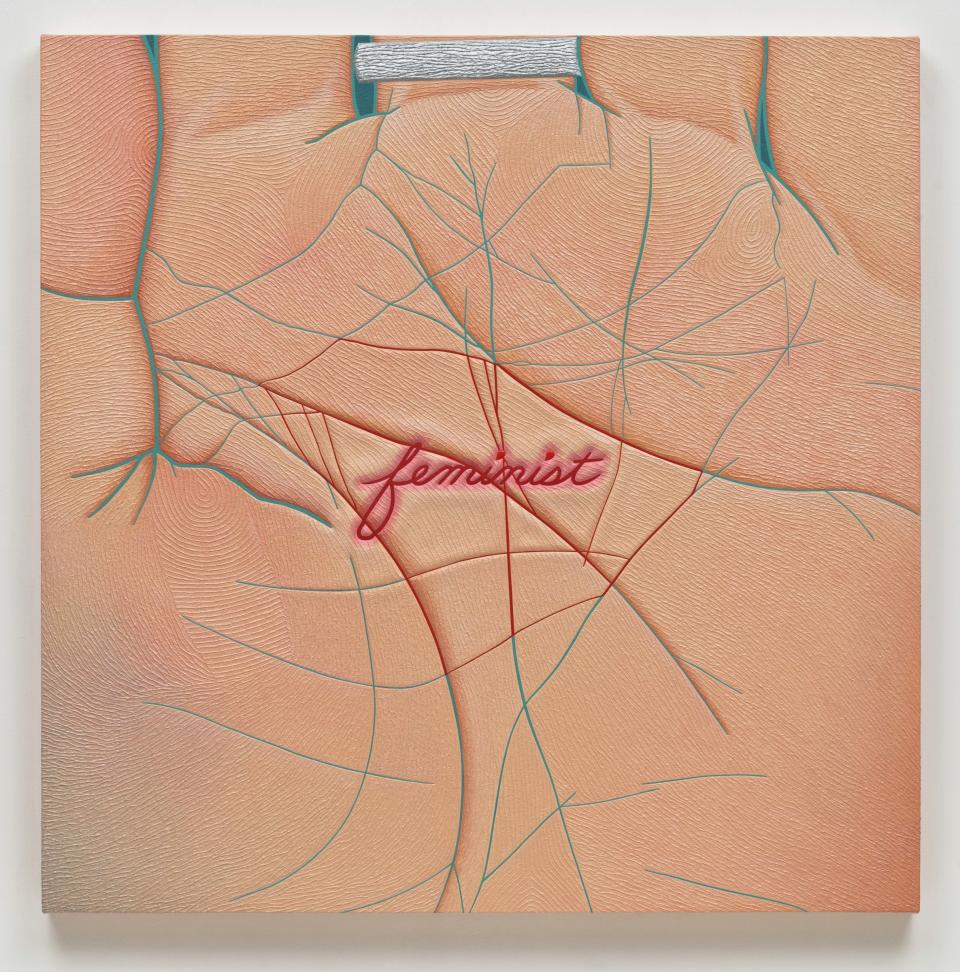

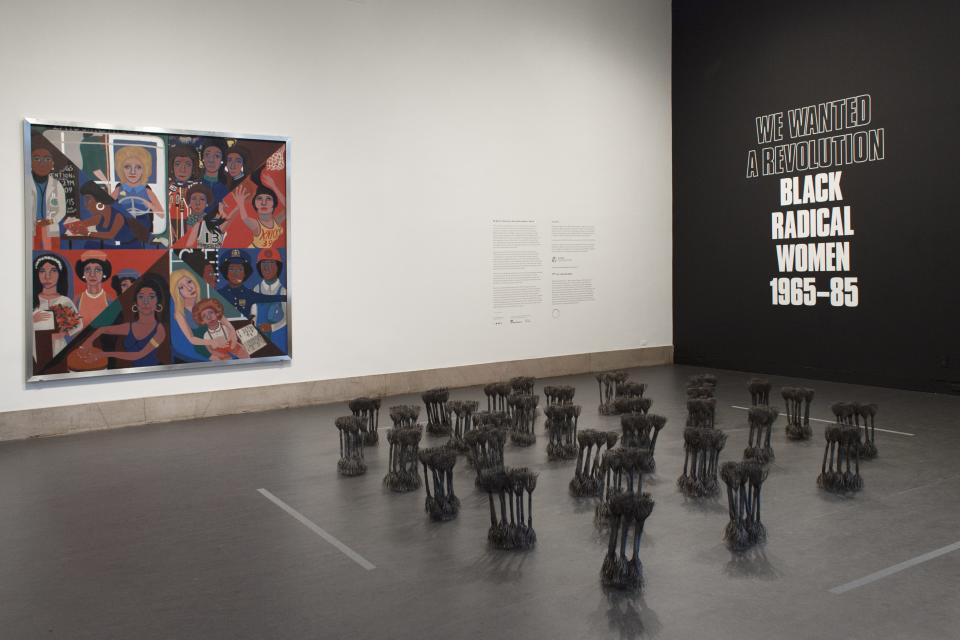

“I’ll never forget that week,” says Morris of the week of the 2016 election, which came just a few days after the Brooklyn Museum opened Marilyn Minter: Pretty/Dirty as part of A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism at the Brooklyn Museum, a series of exhibitions and programming aimed at presenting the history of feminist art. This series also included the 2017 exhibition, We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85, which included O’Grady’s work and provided a springboard for a larger retrospective of the artist.

“One of the things that I think institutions have not done so well a lot of the time is finding structural ways of maintaining change,” Morris says, adding that having the O’Grady retrospective follow in the wake of a group show of Black feminist art is “a quantifiable result of trying to think about how the shows [we curate] can build on each other.” D’Souza, a scholar of modern and contemporary European visual culture and feminist theory, adds that, while the exhibition has been planned well in advance of the FAC’s launch or the November 2020 elections, the current (and, indeed, future) climate can still plausibly show up in O’Grady’s works. “Lorraine is an artist who is constantly revisiting her own work.”

Ultimately, the Feminist Art Coalition has a similar goal: Ask questions that promote engagement and dialogue, rather than offering answers. “I think that’s what’s really crucial, is that it’s centering artists—hopefully not in a way that artists have the answers to everything; rather, this is also what artists are working with,” says Vic Brooks, senior curator at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center, and a member of the FAC steering committee. “It’s a pretty broad spectrum of approaches that are really critically engaged with how we live now.”

“Art is a vehicle for communication,” adds DiQuinzio. “And at its best it’s a catalyst for critical inquiry and critical engagement with the world around you.”

Originally Appeared on Architectural Digest