AI, a party in Nebraska and $1 million: How a UK professor helped decode ancient scrolls

For the first time in 2,000 years, a portion of scrolls destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius have been decoded because of a challenge issued by a University of Kentucky researcher.

And it was done by a University of Nebraska student at a party using artificial intelligence created by UK professor Brent Seales.

The Herculaneum scrolls were burned and carbonized when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE, and have long been considered unreadable. Seales, a computer science professor at UK, has led the decoding efforts for nearly two decades, resulting now in three readable lines of the scrolls.

“These texts were written by human hands at a time when world religions were emergent, the Roman Empire still ruled and many parts of the world were unexplored,” Seales said. “Much of the writing from this period is lost. But today, the Herculaneum scrolls are unlost.”

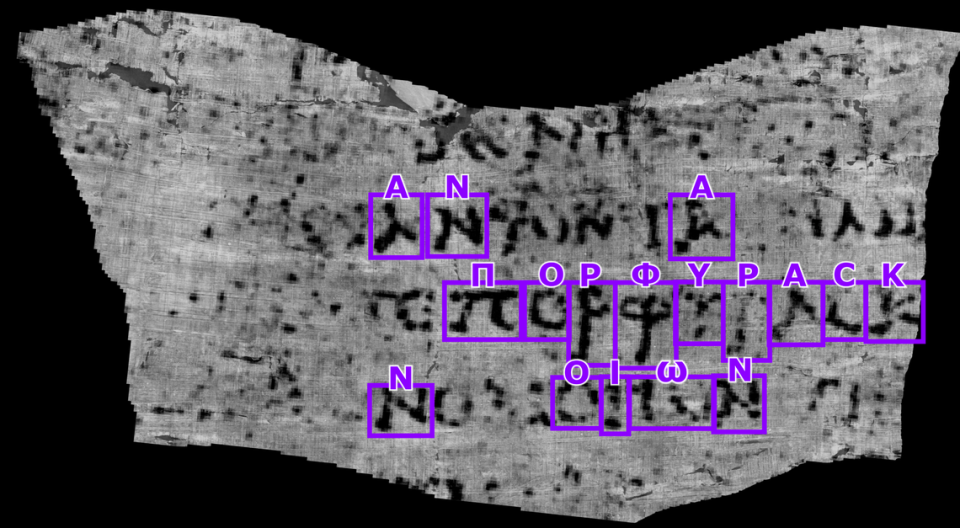

With the Vesuvius Challenge, Seales and a team of Silicon Valley investors launched an international call for people to use artificial intelligence to decode the scrolls. They offered $1 million in prizes to anyone who could decode portions of the text. So far, three contestants have identified text within the scroll, with the Greek word for “purple dye” being the first complete word identified.

Seales said the discovery was emotional, and exciting that it had been made by an undergraduate student, 21-year-old Luke Farritor from the University of Nebraska.

“(It’s) something that people said you would never be able to read because it’s too hard to extract the text, and yet today we’re talking about exactly that,” Seales said.

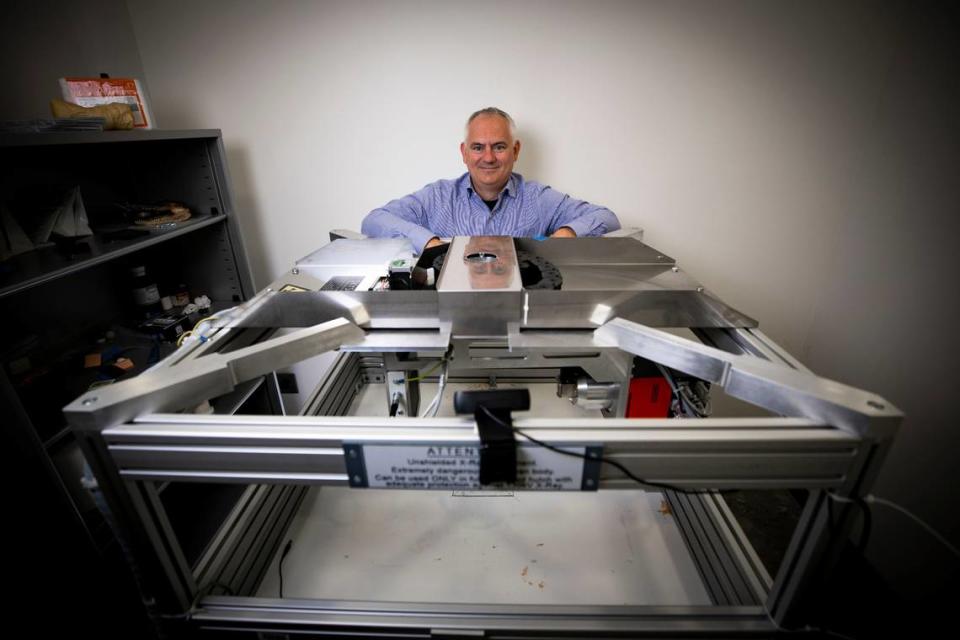

The eruption turned the scrolls into a charcoal-like material. Seales and his team developed a computer program called Volume Cartographer in 2016, which locates and maps 2D surfaces within a 3D object. It was then used to virtually unwrap and read text from the ancient En-Gedi scroll, believed to be one of the oldest Hebrew biblical texts found outside of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

In 2019, the team developed additional ways to read Herculaneum ink, which is made of carbon and invisible to the human eye in imaging.

Earlier this year, Seales’ team released its software, along with thousands of 3D X-ray images of two Herculaneum scrolls, with cash prizes for anyone who can decipher words.

Farritor and Youssef Nader, two Vesuvius Challenge competitors both independently identified the Greek word for “purple dye” earlier this year. Farritor will be awarded $40,000, and Nader will be awarded $10,000 for their discoveries.

Farritor said he first saw the images while at a party one night. He ran the images through the AI program, and later identified the letters. Once he realized what he was seeing, he was shocked.

“I just completely freaked out,” Farritor said. “I almost fell over, I almost cried.”

Still Farritor is not stopping with one word. He’s continued to look at the scrolls and try to reveal a more complete picture of the text. Several days ago, Nader’s model revealed a larger layout of the work, which revealed punctuation marks used by ancient scribes.

A third competitor, Casey Handmer, was the first person to find substantial evidence of ink in the scrolls, and will be awarded $10,000 for that discovery.

“The grand prize is in sight,” Farritor said.

Seales said he expects the scrolls to reveal “writing that expresses what it means to be human.”

“We are human just like they were human, and the gulf that separates us, the 2,000 years, is much more narrow than you might think,” Seales said.