AISD Elementary Teacher of the Year: Connecting with kids is key

"She blinded me with science."

- Thomas Dolby

What's to like best about Taniece Thompson-Smith?

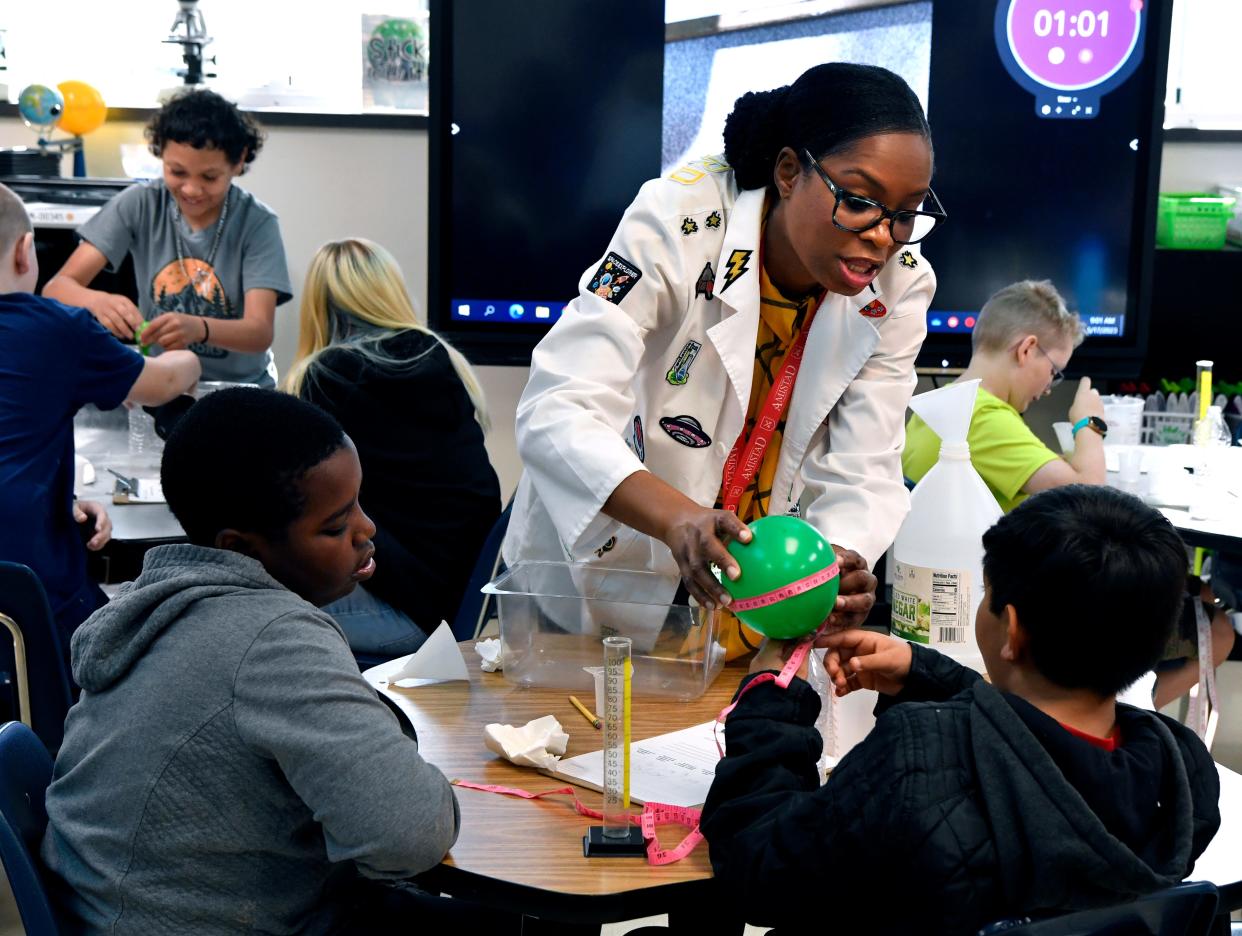

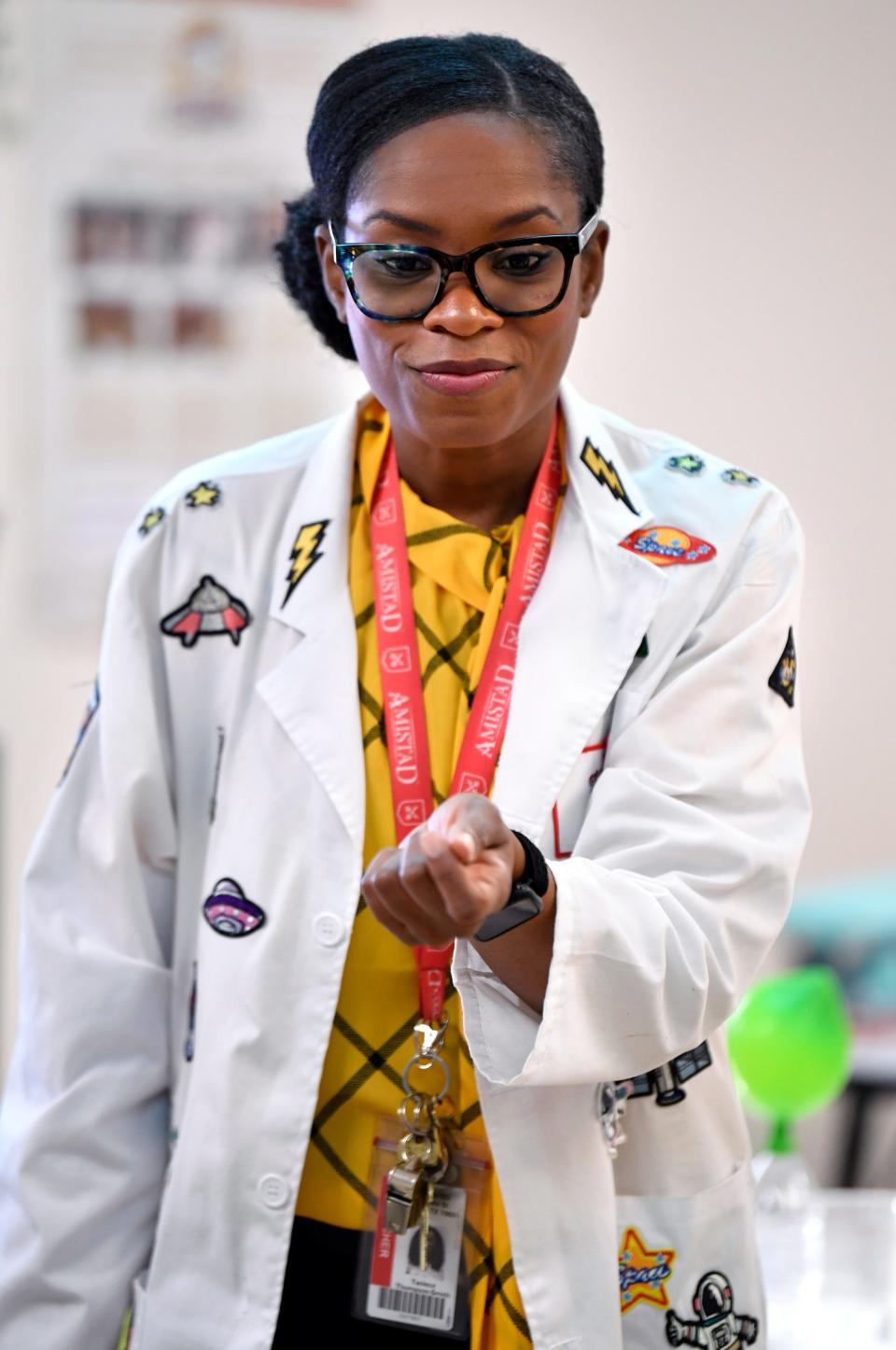

Is it her funky lab coat, the envy of Thomas Dolby, that she wears to teach science at Stafford Elementary School?

Is it her enthusiasm for education?

Is it her durablility - an Air Force wife who moved every time she got settled?

Is it her light Jamaican accent that shows up now and then in conversation?

If this were a multiple choice test, the correct answer would be "all of the above."

Thompson-Smith recently was named Abilene ISD's Elementary Teacher of the Year. That is a stunning accomplishment, considering that she is completing just her second year in the district. She arrived at Stafford, she proudly notes, when the name of Lee Elementary in northwest Abilene was changed to honor two longtime Black educators before integration.

This is her seventh school district, and she is getting a chance to settle in because her husband of 18 years, Theron, made a commitment to her.

You see, she accepted each move - sometimes with tears, she admits - to support her Air Force spouse.

On Friday, the aircraft maintenance supervisor at Dyess Air Force Base retired after 23 years just so they don't have to leave again.

Their twin daughters, Tianna an Tahlia, are sophomores at Cooper High School. The girls will be able to finish at one school for the first time.

"We moved off base and got our Abilene house," she said, smiling. "And I got my Abilene driver's license."

She paused.

"All because of Stafford Elementary," she said. "We changed our retirement plans because I want to see this through. I want to stay long enough to see my students out in the real world."

Doing things differently

Thompson-Smith loves it at Stafford, which has been designated as a model campus. That is, the district has made an effort to place some of its best teachers there.

The teacher who was "recruited" to teach fifth-grade science said the plan is working. She gushes about how students are becoming more engaged in learning. Innovative programs include dividing the student population, regardless of grade, in to houses - a Harry Potteresque approach that builds camaraderie and pushes students to have the best house on campus.

It's in this environment that Thompson-Smith thrives. She admitted that she eagerly accepted the challenge of teaching science without thinking it through. Though she's a confident woman, she may have bitten off more than she should have, she thought later.

But she has studied the subject and learned with the youngsters. They are in this journey of discovery together.

What's most important, she said, is getting them involved. Whether it's guests such as a geologist coming to the classroom with examples of fuel sources, a donation of a cow's skull to illustrate adaptation to the environment or taking a school field trip to see what critters make a home in other classrooms, she wants them to experience learning and have fun doing it.

How about a school nurse, who offered to bring a horse to the campus?

That got cleared and, Thompson-Scott said, some students saw a real, live horse for the first time.

To prepare for STAAR testing, benchmark testing is common in the district. Teachers then know what deficiencies to address before the real test is taken. Thompson-Smith employed various strategies. For example, creating stations in the classroom at which three or four students, working with an adult (her husband was a volunteer), focused on a specific study area.

Later, when the students took a previous STAAR test as practice, "They smashed those questions," she said.

Her Stafford Lions roared.

Coming to America

Thompson-Scott was raised in Montego Bay, Jamaica.

She finished school there at age 16 - that is the norm - and was two years into gaining her three-year college certificate when her mother brought her children to the United States.

"For a better life. Jamaica is a third-world country and America is known as the land of dreams," Thompson-Smith said. Her father had a business and stayed to work; her mother took whatever jobs she could to make a living here, believing in the opportunity for the four children.

"My parents worked hard and always saw each generation doing better. So I stand on the shoulders of very hard-working, poor people who were rich in love, rich in kindness and understanding the value of education."

Her mother, who did not go to college, understood, too, that her hard work "would result in her kids doing better."

She goes to Jamaica to see her father. Her brother retired from the military, she has a sister in Florida and another in New York.

Education was key. So was not giving up. And you have to stay the course, her parents said.

"They instilled in me that whenever you start something, finish it," she said. "So I was never a quitter."

Trials of being a teacher

Thompson-Smith's goal was to become a teacher.

Then came the 1999 shooting massacre at Columbine, and she changed her mind. Never had guns and education mixed in her life.

Living in New York City, she was encouraged to get a degree in computer information science and worked in a hospital as a programmer. Though in her role she helped people, it wasn't that personal contact she sought.

"The intrinsic value was not there," she said. "I was helping people, but not in the way I envisioned."

She had married by then and expressed to her husband that her job calling was unfulfilled.

So, she went back to school to resume her quest to become a teacher.

She found her dream job at Chesterfield Elementary in New Jersey - "my one and only job for life," she said, laughing. "For the first time since I had come to America, I was doing what I had dreamed of all my life."

Then her husband was assigned duty in California.

It was time to start again. She got her master's degree at California State University-Fresno.

Thompson-Smith landed another dream job.

"I fall in love easily when it comes to career, I don't know why," she said, shrugging.

She was a full-time, independent studies high school teacher. These were students on the edge, maybe kicked out of school or pregnant. She posted work online for students, who then received one-on-one instruction from her once a week - an hour to 90 minutes. Not at school but at a Starbucks or the library.

She treasured talking about their goals and how education could get them there.

"And they had my undivided attention," she said. It's something she has incorporated into her instruction at Stafford.

"I can't put a price on it."

Their California experience lasted another four years.

Then came the experience of teaching at a Japanese primary school, where she wore four types of shoes - one for the subway, one around campus, one in carpeted areas and even slippers to be worn only in the restroom. Students were required to brush their teeth at school.

What the new teacher offered was the American "big heart and warm, fuzzy feeling." That is not generally part of Japanese culture but it worked with the students. Unfortunately, she was there when COVID struck and the hugs and such had to stop. She noticed the difference in the students' attitudes at school.

She had connected.

It then was back to the States and on to Texas. The Smiths had to search for Abilene on a map, and their only visual, she joked, was an online tour of local coffee shops offered by a local Realtor.

They settled in on base and her daughters had to work through distance learning, as did other Abilene students.

Mom felt called back to education.

Being stellar at Stafford

Thompson-Smith brought this world of experience to Stafford, though she had to find the school first.

She didn't know where the district's administration office was downtown or the location Stafford. She had to use GPS to find both.

When she found Stafford, she found yet another dream job.

The campus employs a teaching model that's taught at Ron Clark Academy in Georgia. AISD administrators went to Atlanta in 2019 after then-Lee Elementary received an "F" in its state accountability rating.

Teachers are selected specifically for Stafford and, most importantly, she said, want to be at the school. That forms a unique partnership. Teachers were other schools are invited to campus to observe, with the goal to take what they witness back to their campuses.

The students come first, it quickly was clear. That was in her wheelhouse.

"My goal has always been, put my students first," Thompson-Smith said. The demographics of the students have not changed, she said.

"What has changed is that we have a clear goal. We have high expectations. Our goal is that we are personally invested in the success of every student."

How is that defined? Thompson-Smith said students learn what education can do for them now, in the future" and how you look at your past."

Students have responded to having goals and the consistency in the approach, she said.

Though an experience educators, she found mentors in Stafford Principal Melissa Scott and Janaye Wideman, who now is the principal at Dyess Elementary. Thompson-Scott learned about the schools' past and its new place in the AISD.

"Boy, am I privileged to be part of this. You have no idea of the caliber of teachers in this school. Everything I am deficient in I have a person here I can go to and help me," she said.

"And students need to be love, appreciated and respected the same way we love and appreciate and love adults," she said.

To her, elementary education is about experiential learning.

"My goal was to bring science to life," Thompson-Smith said. "Not just for the students but for myself. I felt like I was back in school."

In her decorated lab coat, she looks like a science teacher.

"Now I think I want to be a science teacher for the rest of my life," she said, smiling broadly. "Like, 'Science, where have you been!'"

This article originally appeared on Abilene Reporter-News: AISD Elementary Teacher of the Year: Connecting with kids is key