Akron funeral director won’t object to parole of parents’ killer 50 years ago

After decades of providing comfort to grieving families and shepherding mourners through traumatic losses, David Anthony came to a gradual realization.

He needed to search his heart for forgiveness.

Anthony, 68, a resident of Green, is owner, president, funeral director, embalmer and cremationist at Anthony Funeral Homes of Akron.

“At least every other week, I have people come into the funeral home and ask me if I’m related to the Anthonys that were killed,” he said.

Fifty years ago, his parents were murdered in a random crime that shocked Akron.

Paul P. Anthony, 47, chairman of the Kucko-Anthony-Hecker Funeral Home, and his wife, Patricia, 39, a teacher at Sacred Heart Catholic School in Wadsworth, were found slain Feb. 27, 1974, at Perkins Woods in Akron. Police discovered the Wadsworth couple face down in the snow at about 5 a.m.

He clutched a rosary and she held a crucifix.

Both had been shot once in the back of the head with a .38-caliber gun, presumably as they prayed.

They left behind six children: Paul, 19, David, 18, Peter, 16, Mary Pat, 15, Daniel, 12, and Julie, 10.

“To me, that event was when Akron grew up,” Anthony said. “We turned from a small town with a lot of people to a big city with not that many people. This kind of stuff just didn’t happen in Akron back then.”

Anthony is surprised by how many residents recall the tragedy in detail.

“I am really stunned at the number of people who remember Carl Bayless’ name,” he said.

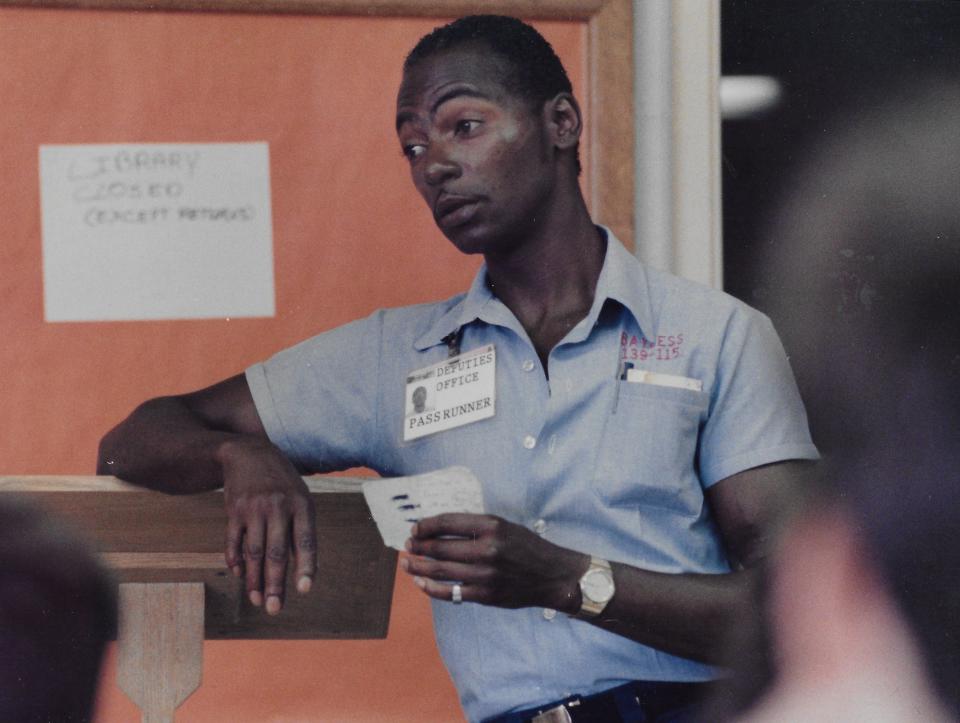

Bayless, who will turn 68 on Feb. 28, is serving a life sentence at Grafton Correctional Institution after being convicted of murdering Paul and Patricia Anthony when he was 17. Ohio law requires parole hearings every five years for people found guilty of committing serious crimes as juveniles.

Bayless’ next parole hearing is set for May. He could be released July 1.

For decades, Anthony worked to keep the inmate behind bars, but his feelings have changed. This year, he doesn’t plan to object to Bayless’ release.

“I don’t know,” Anthony said with a sigh. “I guess I think it’s been long enough.”

He and Bayless have exchanged letters, and Anthony hopes to visit him in prison.

“I really just want to be an example of forgiveness,” he said.

Double murder in Perkins Woods

Paul and Patricia Anthony went missing Feb. 26, 1974, after visiting her father, Andrew J. Kucko, the founder of Kucko Funeral Home, at Akron General Medical Center. He was recovering from a heart attack after his wife, Mary, died Feb. 15.

Paul Anthony had a doctorate in chemistry and joined the family funeral business in 1971 after 13 years with PPG Industries. Patricia had taught fifth grade for three years at Sacred Heart.

Investigators theorized that the couple stopped at Kmart on Wooster Avenue before 9 p.m. on the way home to Wadsworth. According to police, a gunman confronted them in the parking lot, forced them into the trunk of their car, drove them to Perkins Woods, robbed them of their valuables and shot them to death as they prayed. The killer drove off in their 1973 Cadillac.

That evening, David Anthony, a University of Akron freshman and 1973 Walsh Jesuit graduate, was rushing to beat curfew.

“I came home that night and I was 30 seconds ahead of my ‘You gotta be home by this time,’” he recalled. “I popped into the door with kind of a ‘Ta-da!’”

He was surprised to find his little brother babysitting the youngest siblings because their parents hadn’t come home. Their oldest brother was away at college in New York, so the boys made calls, but they couldn’t find their mom and dad. Not knowing what to do, they went to bed.

Anthony telephoned police at 6 a.m.

“I called Akron and they said, ‘You’d better come down to the station,’” he recalled. “So I went to the station. You know at that point there’s something pretty serious. There’s no way they wouldn’t have contacted us had they been alive.”

Detectives confirmed his worst fears: His parents were dead. Overnight, the Anthony children’s world had shattered.

A double funeral was held March 2 at Sacred Heart Catholic Church.

“You have received a very beautiful heritage,” the Rev. Thomas G. McMahon told the six orphans during the eulogy. “That is the love your parents had for you. … I don’t ask you to become like your father or like your mother. I ask you to be yourselves, your own personality, taking the beautiful things your parents have taught you.”

Paul and Patricia Anthony were buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Akron.

Carl Bayless charged in killings

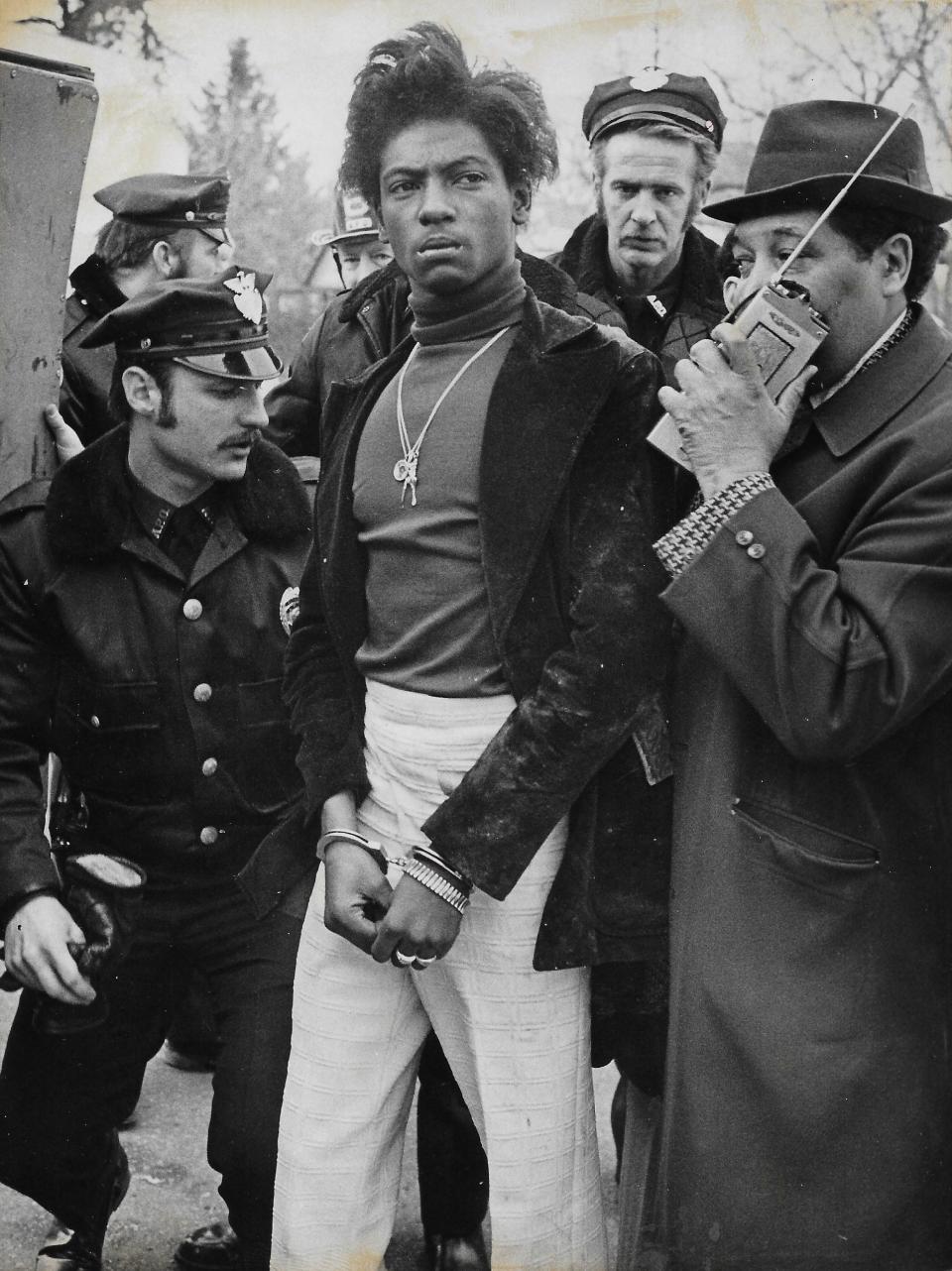

Investigators arrested a suspect within hours of the slayings. Acting on an anonymous tip, Akron police arrived before 9 a.m. Feb. 27 with a warrant at the Bayless family home on Dorothy Avenue just a few blocks from Perkins Woods.

It was the day before Carl’s 18th birthday. Police said the agitated teen initially threatened to shoot them, but eventually tossed down a .38-caliber revolver and surrendered. Ballistics tests later linked the gun to the slayings.

Police reported finding Paul Anthony’s wallet, Patricia’s wedding ring and other belongings. Their Cadillac was parked in a driveway on Bellevue Avenue behind the Bayless home.

Investigators also recovered $319 from a Copley Road restaurant that had been robbed at gunpoint the night before.

Authorities learned that Bayless had escaped an Ohio Youth Commission group home Nov. 2 in Columbus, where he had been sentenced to seven years after pleading guilty to delinquency by reason of first-degree murder in another slaying.

Bayless was 14 when he killed retired Firestone chemist Francis K. Means, 66, during a failed holdup attempt Sept. 2, 1970, in Akron. Two youths confronted Means and his wife, Geneva, as they took an evening stroll near their home on Greenwood Avenue. Officers said Bayless shot Means in the chest and the teens fled without cash.

Police arrested Bayless in Detroit. His crying mother said he had been a good kid until he started hanging out with “a bad crowd” and became a runaway. Acting on an anonymous tip, officers found the murder weapon wrapped in a red cloth at Perkins Woods.

Bayless admitted to killing Means but pleaded not guilty in the shooting of the Anthonys. He was tried as an adult in May 1974.

David Anthony remembers testifying at Summit County Common Pleas Court. An assistant prosecutor showed him photographs of the murder scene and asked him to identify the victims.

“That is my father and my mother,” he told the court.

He doesn’t recall whether he looked at Bayless from the stand.

“We might’ve glanced at each other,” he said. “I really didn’t want to. I was just trying to keep it all together.”

A jury convicted Bayless of two counts of aggravated murder May 9. Judge James V. Barbuto sentenced him to the electric chair May 28.

“We were ready to be done with it,” Anthony said.

Learning the funeral business

Anthony became the legal guardian of his four younger siblings while their aunt, Mary Kucko, served as custodian. He had worked part-time at the funeral home but decided to make it his career.

He quit UA to attend the Pittsburgh Institute of Mortuary Science, where he graduated in 1976. After serving a one-year apprenticeship, he became a licensed funeral director and embalmer in 1977.

For the first 20 years, he felt like a little kid doing a big person’s job.

“It was like, ‘Oh, you’ve got to take over the family business,’” he said. “But I learned to love it and realized that I was pretty good at it and enjoyed it.”

David married Diane Harouny, a registered nurse at Akron Children’s Hospital, in January 1978.

That same year, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Ohio’s death penalty, vacating the death sentences of 53 convicted murderers, including Bayless. The sentences were reduced to life in prison.

In 1981, Bayless escaped from a medium-security farm detail at the Marion Correctional Institution.

FBI agents captured the fugitive four months later in Oakland, California. He has been behind bars ever since.

Killer says he’s changed

Bayless' first Ohio parole hearing in 1989 came as a shock to the Anthonys.

“We thought that life in prison meant life in prison,” Anthony said.

Back when he was against Bayless’ parole, Anthony argued: “There is supposed to be just retribution for crimes. I don’t think he should serve anything less than the entire life service."

The hearings, which now come every five years, are no longer a surprise, he said. Bayless has been denied parole each time.

In a 1994 interview in prison, Bayless said he was reformed. If paroled, he said he would repay society by counseling troubled youths.

“I can’t bring the Anthonys back,” he said. “If the Anthonys are in heaven looking down, I hope they would hope that I came out of this a positive person instead of a negative person.”

When he looked in the mirror, he said, he no longer recognized the teen who fired that gun in 1974.

“I can’t tell you why I felt I had to shoot them,” he said. “There was a storm in my head. I was as afraid as they were. I knew that if I left them, they would call the police.”

Finding forgiveness through Lord’s Prayer

The 1974 murders have had ripple effects over time. Anthony hasn’t specifically been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, but he does take medication for anxiety and depression.

“It’s chemical imbalances,” he explained. “A lot of time it’s brought on by stress.”

He remembers how his path to forgiveness began in the late 1990s at St. Francis de Sales as he listened to the Rev. Charles Byrider discuss the Lord’s Prayer.

“He gave a homily on the ‘Our Father,’” Anthony recalled. “He said the Word is, ‘Forgive us our trespasses AS WE FORGIVE THOSE who trespass against us.’

“It’s not ‘Forgive us because we are basically good people and we try really hard,’ or ‘Forgive us because our sins really aren’t all that bad.’ It said, ‘Forgive us the way we treat everybody else.’”

That got Anthony to thinking: Sin is not subjective. Sin is sin. It harms you and other people.

“That, for me, then is being forgiven for the things I may or may not have done,” he said. “It requires me to be able to do the same for other people.”

It’s not just about forgiving Carl Bayless.

“Understanding that I need forgiveness is part of it, too,” he said. “We both do.”

It’s healthy to forgive

Anthony has spent a lot of time learning about forgiveness and discovering how vital it is to mental, physical, social and spiritual health. He’s spoken to different groups on the subject and attended continuing education classes to learn more.

As a counselor friend once told him: “Not being able to forgive is like letting somebody live inside your head rent free.”

People need to forgive to find peace, he said. Otherwise, it’s just too draining. If you’re focused on revenge, you’re not going to be able to focus on other things like grief, he said.

Anthony thinks Bayless was a product of turbulent times in Akron. He was a Black kid growing up on the streets in a system that failed him.

“I think racism had a lot to do with creating the environment which created him,” he said. “I mean, we took people and crammed them into a limited area and told them they were 'less than,' and said, 'You’re on your own. Pull yourself up.'”

He has heard bigots say loathsome things about Bayless and other people of color, and he wants no part of that. Hatred isn’t the answer.

That doesn’t mean that Bayless should be excused for what he did, Anthony said. He said he has never felt like he’s “a bleeding heart.” In fact, he owns a gun.

“People have got to be responsible for their actions,” he said.

Against the death penalty

Over the years, Anthony has done a great deal of thinking about the death penalty and has decided that it serves no purpose. It is “capriciously enforced, unfairly applied, worthless as a deterrent, and used by politicians to generate support for themselves from hateful people,” he said.

Plus, it’s incredibly expensive.

“It costs less to incarcerate somebody for 50 years than it does to try a capital murder case with a death penalty specification,” Anthony said.

He’s known people who’ve “had their pound of flesh” and still been dissatisfied.

“All that anger and effort you put into hating someone enough to want them to die prevented you from grieving,” he said.

About four months ago, Anthony applied for permission to visit Bayless at Grafton. He also exchanged letters with the inmate, who seems receptive to a meeting. The warden has yet to approve the visit, but Anthony is hopeful.

Anthony doesn’t plan to challenge Bayless’ parole this time, and although he’s unsure what his siblings will do, he knows at least one feels the same way.

“He’s paid for the crime,” he said. “He spent 50 years in jail.”

‘That’s what a bullet does’

At the Kucko-Anthony-Kertesz Chapel on South Main Street, Anthony brought out a scrapbook filled with yellowed articles about the murders of his parents and the trial of their killer.

He recalled going to the prosecutor’s office around 1995 to salvage the contents of an evidence locker from the 1974 trial.

“They were just going to throw everything away,” he said.

He retrieved his parents’ bloodstained clothing and personal effects, including the rosary and crucifix that they had held in their final moments. Mindful that his mother’s engagement ring had never been found, he searched carefully.

“Damned if it wasn’t in the finger of one of her gloves,” he said.

Patricia Anthony had secretly slipped off the half-carat diamond in a platinum setting so that her robber wouldn’t find it.

“It was stunning,” Anthony said.

Years ago, he visited the site where his parents were killed. It’s now a part of the wolf habitat at the Akron Zoo. He walked along the paths and thought about all that transpired.

“I just needed to go,” he said.

In a wrinkled yellow envelope, he’s kept two tiny cardboard boxes labeled Exhibit 68 and Exhibit 70. Inside the boxes are little transparent bags holding two mangled bullets.

“These are the slugs that were pulled out of Mom and Dad,” he said.

Holding them gingerly in his hands, he explained why he’s kept them.

“They’re kind of relics, I guess,” Anthony said. “They’re an important part of the story. I mean, they’re real. ... To look at those is to say ‘That’s what a bullet does.’”

And besides, what else should he do with them?

“Just put them in the trash?” he asked.

Overcoming loss and grief

At the main entrance of the South Main Street chapel, Anthony has installed a plaque: “Dedicated to the memory of Paul and Patricia Anthony and to those who will rest here a short while whose brief presence makes this building sacred in a way no mere words can express.”

The tragedy has helped Anthony better understand and address the needs of grieving families. When he meets young people who’ve lost a loved one, he wants them to know that they can heal in time.

“The grief does not feel good, but it is good for you,” he said. “It’s how we process. It’s how we take life the way it was before and reconcile with the way it’s going to be down the road.”

Anthony said his siblings have done well with their lives, becoming a physician, an attorney, a nurse, a teacher and a federal emergency worker. All have happy marriages and lots of kids.

Anthony and his wife, Diane, have been married 46 years and belong to Queen of Heaven Catholic Church in Green. Their children Eric, Adam, Lauren and Katherine have blessed them with seven grandchildren. Eric and Katherine are the fourth generation to enter the funeral business.

A long time ago, Anthony learned that people have two choices when dealing with a traumatic loss. They can turn it into a victory or they can keep losing.

“If you let it destroy your life, you’ve lost twice,” Anthony said. “If you somehow turn it into something that can be good for you, then you win from it.”

Mark J. Price can be reached at mprice@thebeaconjournal.com

Unresolved: Looking back at unsolved cold case murders from the Akron area and beyond

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Funeral director David Anthony ready to forgive killer Carl Bayless