Akron NAACP event showcases Ohio NAACP's focus on civil rights in education for 2024

Ivory Toldson’s mother attended lawfully segregated schools and his grandfather’s grandfather, who's mother was raped as a slave, received an education on a southern plantation with his white half brothers.

As a Black kid born in Louisiana, Toldson’s education in the 1970s and 1980s would be different. It would benefit from a 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that ushered racial integration in schools and the 1964 Civil Rights Act that outlawed discrimination based on race and skin color.

But efforts to desegregate American schools had Toldson taking a bus from his predominantly Black neighborhood in North Baton Rouge to a school across town where, to his surprise, his classmates were still overwhelmingly Black.

“You might say, ‘Why would they bus me from my own neighborhood to go to another predominately black high school?’” said Toldson, the keynote speaker for the 2023 Akron NAACP Freedom Fund Event. “It’s because the bus routes [to racially integrate schools] could not keep up with the white people running away from us.”

The early dinner event on Sunday at the John S. Knight Center was the Akron NAACP’s premier annual fundraiser. Donations and ticket sales fund much of the organization’s advocacy, voter registration drives, community outreach, education programming and more.

The event, as captured by Toldson’s retelling of his personal experiences and family history, also brought into focus a top priority for the Ohio NAACP in 2024: education.

From pushing for an education system where Black experience is authentically standard instruction to rethinking the racial implications of standardized tests, nothing will be a higher priority, Ohio State Conference NAACP President Tom Roberts said after the event in downtown Akron.

The dinner fell again this year two days before a critical November election.

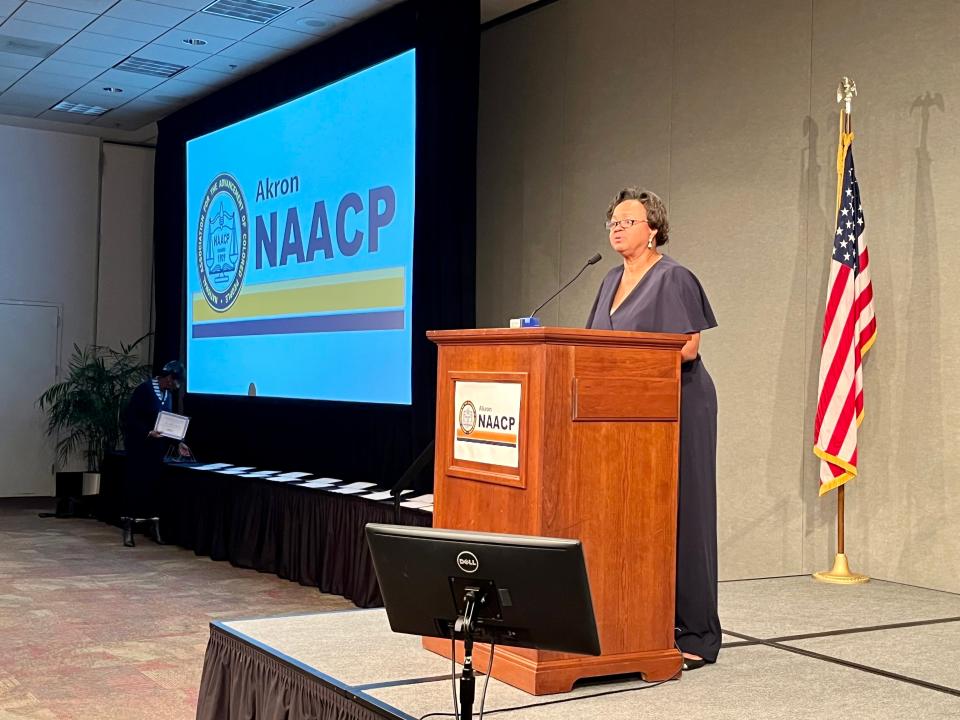

Akron NAACP President Judi Hill and Toldson urged the hundreds of Black civic and professional leaders in attendance to elect candidates who support minority people at every level — starting with the school board race in Akron.

“We recognize that education is critical,” said Hill, a retired teacher.

“It’s not just about learning, knowledge, acquisition, preparing yourself for a job before your future,” Toldson said. “… For Black people, education has always been about liberation.”

Education and race in Akron

Hill took her first teaching job in Akron at Voris Elementary School in 1979. The district wanted more Black teachers like Hill as mostly white schools received an influx of Black students.

It was a radical time in America as court orders in Columbus and Dayton mandated integration through bussing. Akron, which was under a court order to hire more Black police officers, was closing Black schools to save money and spreading the displaced students across the district to achieve desegregation.

The ACLU in 1968 and 1978 sued Akron Public Schools, the city, the Ohio Real Estate Commission and Akron Metropolitan Housing Authority over discriminatory housing practices and targeted school closures that concentrated Black people while keeping white schools mostly white.

By March 1979, the Akron school board had closed three elementary schools under the “Akron Plan.” Shuttering Robinson Elementary and Thornton Junior High that year would have sent 1,350 more Black students (15% of all Black kids in the district) and 300 more white students (1.4% of all white kids) on a bus to a different school.

Critics, including the ACLU and the NAACP, criticized the plan for continuing to put the burden of school desegregation on the backs of Black kids and their families. When Grace Elementary closed in 1977, 95% of the 290 kids bussed to a new school were Black. The same happened to Bryan Elementary, an all-Black school, in 1978.

The district closed three more predominantly Black schools in the fall of 1980: Lane Elementary, West Junior High and South High School. But while the school board declared victory in the ACLU lawsuit, the litigation included a settlement that kept Robinson Elementary open.

Toldson credits 'dope' mother, amazing teacher for his success

Toldson, the grandson of civil rights activist John Henry Scott, was graduating from high school at the time.

In fourth grade, he was more likely to be counting burnt out light bulbs or dots on ceiling tiles than learning at the private school he was attending in Baton Rouge, he told the crowd Sunday.

But his mom would not “continue to pay for private schooling for D’s and C's,” so she pulled Toldson and put him in a public school where a teacher, Ms. Law, changed his life.

“She thought I was gifted,” Toldson said, realizing for the first time that he learned differently, not slower.

After graduating with a master's in counselor education from Penn State, his mother would gift him with a life-changing trip to re-trace the Underground Railroad from Louisiana to Canada, with several stops through Ohio.

Along with Ms. Law, he gave the credit of his success to his mother, who connected him to his past in a way that “offset some of the challenges” he experienced in school. Today, he is a professor of counseling psychology at Howard University, national director of Education Innovation and Research for the NAACP, editor-in-chief of the Journal of Negro Education, executive editor of the Journal of Policy Analysis and Research for the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation and former President Barack Obama appointee to a task force to support Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

In this era of heavy testing and education reform

Toldson said his mother attended school in the “separate-but-unequal" era of redlining and other overtly discriminatory practices. Toldson learned in the desegregation era with its white flight. The late 1980s ushered in the era of education reform. Schools don’t need to be racially balanced, he said of the thinking, if they teach the same standards.

But, he asked the crowd, who sets the standards? Standardized tests, which he argued measure scores and not achievement, always told him he was performing “below basic.” He “had to get a psychology degree” to understand the impact this is having on more than his own education.

Toldson questioned the lack of attention to wider "achievement gaps" between Asian and white students than white and Black students.

"Why," he asked, is no one questioning that? "Because we have normalized whiteness, we are setting up a system where that becomes a norm. And if you're doing better than that, then you're just doing better than you need to be doing.

“We have been burdened by all of this noise and all this mantra from the reform era. We're missing talent. We're labeling children. We are taking people who are like me when I was a child, and but for the grace of God — that put me in a new class where a teacher was able to undo damage pretty early and my mother who was empowering me with his knowledge of self — but for that, I'm not where I am right now," he said.

“How do we create a system where we are revealing talents, as opposed to exposing weaknesses?" he asked. "How do we create a system where Black history isn't something that you get because your mama is dope, but you get it because it's baked into our school system?”

Reach reporter Doug Livingston at dlivingston@thebeaconjournal.com or 330-996-3792.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Akron NAACP speaker retraces the racial roots of American schools