Akron refusing to identify officers who fatally shot suspects, explain decision

The city of Akron is refusing to promptly identify officers who shoot and kill civilians, even after the officers are back on the job.

The city has previously identified officers under investigation for using deadly force. But officers' names and records are being withheld for fatal police encounters in December and February.

In the December incident, an officer killed a man holding a knife to his estranged wife's throat. In February, two officers fired into a Ritchie Avenue home, killing a young man ordered multiple times to drop a handgun.

In March, the Akron Beacon Journal requested the names, disciplinary records and personnel files of the officers involved in both incidents. Three weeks later, the city law department denied the request in a letter citing a handful of exemptions in state laws.

Akron Police Chief Steve Mylett would not comment on the city law department's decision to withhold the information.

But in October 2020, the city provided the Beacon Journal with names of every officer with a recorded use of deadly force since 2004. The list included four incidents that, at the time, were still under investigation.

The Akron Police Department's Office of Professional Standards and Accountability reviews each incident, producing a report that gets forwarded to the Akron Police Auditor. The matter is then reviewed by outside agencies.

These external audits were handled locally until 2020 when Summit County Prosecutor Sherri Bevan Walsh, citing her office's close working relationship with Akron police, decided to turn over all use of force investigations to state investigators. The Ohio Attorney General's office now conducts the external reviews, presenting evidence to Summit County grand juries that have so far declined to indict local officers who use lethal force to protect themselves or the public.

The Beacon Journal is seeking the names to enable reporters to request personnel and any disciplinary records for the officers, Editor Michael Shearer said. He raised concerns with the city's records release with Mayor Dan Horrigan on April 15.

"While the city is now releasing videos of these incidents, the public has a right to know which officers used deadly force and whether they have a clean service record or not," Shearer said. "We respect the dangerous work officers perform, but believe the public has a right to more transparency."

The city has not responded to the Beacon Journal requests for an explanation of the matter other than clarifying one issue.

In denying the Beacon Journal’s request for the names, personnel files and disciplinary records of officers involved in the Dec. 23 shooting death of James Gross and Feb. 23 shooting death of Lawrence LeJames Rodgers, a city attorney cited exemptions in Ohio’s Open Records Act.

The attorney said the records are part of active investigations, the officers are uncharged suspects in those ongoing investigations and releasing their names “would endanger the life or physical safety of law enforcement personnel,” according to the sections of Ohio Revised Code cited in the letter denying the release of the records.

Bodycam video: Akron police video, audio from officer-involved shooting

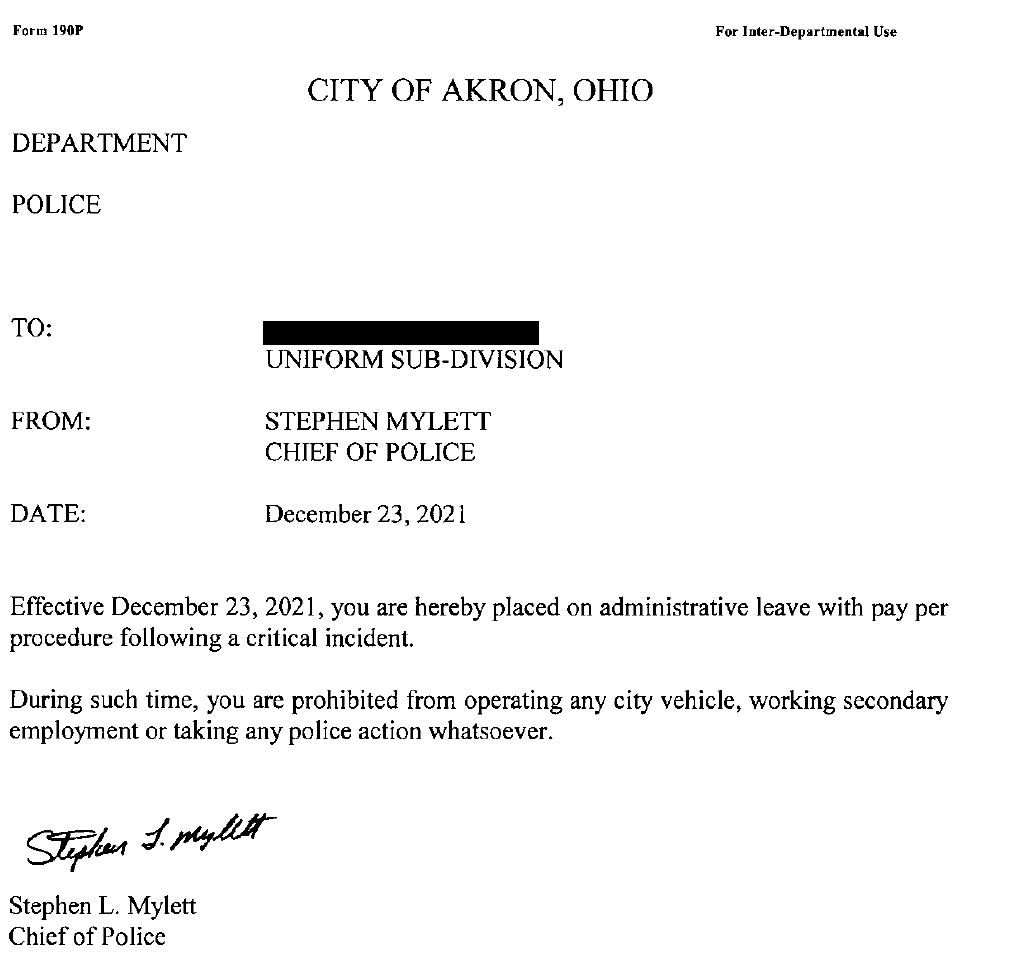

The names of the officers involved in the February incidents are blacked out in administrative leave documents the city provided to the Beacon Journal.

The officer who shot Gross in December was cleared by an internal investigation and returned to “full duty status” on Jan. 4, according to the redacted records.

Two other officers were free to “return to their regular duty assignments” March 18, nearly a month after being placed on paid administrative leave, according to the redacted records.

Officers placed on leave for deadly force by dhlivingston on Scribd

Initial police reports for each incident list the names of witnesses and suspects. The offenses listed for Gross include domestic violence and violating a protection order. Rodgers is listed for the murder of his cousin.

A third offense — deadly force — is listed on each report, but there's no officers' names associated with the charges, not even black boxes where the names should be.

Other than stating that detectives and a crime scene unit were present, the entire narrative for the February report reads: "Suspect shot victim. Officers used force."

Not only are the details scant, they're out of order. Officers first shot Rodgers who then shot the victim.

'What happened?': Family of man killed in officer-involved shooting in Akron wants answers

After speaking with police commanders who handle major investigations, Deputy Law Director Christopher Reece said the police reports are created to start the investigation. Police intentionally omit names of officers who, until cleared by the investigation, may also be considered suspects in homicides.

"In an Akron Police Department homicide incident report, suspects are rarely, if ever, listed or identified as a matter of course," Reece said in an email. "An officer involved shooting is a homicide incident."

The city also claimed the personnel files of the officers were confidential law enforcement records, although media and citizens regularly obtain such records for public employees.

"Ohio’s public policy is one of transparency, and under Ohio law, as stated by the Ohio Supreme Court, the obligation of a City to provide records is construed liberally in favor of broad access, with any doubt resolved in favor of disclosure of public records," said attorney Lynn Larsen, who represents the newspaper.

"While some types of records — such as active investigation files of police — are exempted, those exemptions are narrow and limited. They don’t apply to requests, like the ones made here, for administrative files that show which police officers were put on, or returned from, administrative leave. Those types of documents relate to the employment and performance of municipal employees, paid by tax dollars and entrusted with the use of deadly force, and the public has a right to receive and inspect them."

No standard for releasing names

There's no standard procedure for when or whether city officials should name officers who use deadly force. Some cities volunteer the information before the media requests it.

Others police department fight to keep the names hidden, even after external investigations have concluded.

Police departments and mayors have adopted administrative policies blocking or delaying the release of names. In some cases, though not in Akron, police union contracts prohibit public disclosure.

Last year, Beacon Journal owner Gannett Co., Inc. and its local newspaper, the Tallahassee Democrat, joined the city of Tallahassee in objecting to the Florida Police Benevolent Association's position that officers attacked or threatened by suspects are actually victims of crimes afforded anonymity under Florida's version of Marsy's Law.

The city of Tallahassee was prepared to name officers when the police union sued. The case is now before the Florida Supreme Court.

When denying records requests, local agencies in Ohio most often cite exemptions in the state's Sunshine Laws, said Dave Licate, professor and chair of Criminal Justice Studies at the University of Akron.

"Obviously, you want to protect the investigation. You want to protect the safety of the officer," Licate said. "But you have tension there between public safety and the right of the public to understand what the police are doing and who's doing it."

The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF), a national organization that develops best practices in policing, recommends that office-involved shootings should be followed by the release of "as much information as possible to the public, as quickly as possible, acknowledging that the information is preliminary and may change as more details unfold."

The national organization, however, stops short of recommending that officer names be released or withheld from the public. But like Licate, PERF acknowledges the need for a consensus among the nation's more than 18,000 law enforcement agencies.

"There's no standard," said Licate. "It would be nice to have model policy, model procedure and guidance, maybe more research on the issue."

Akron posts videos of body camera footage within seven days of an officer using deadly force. The footage can capture the faces of the officers but not their names.

Licate said the naming of officers is part of the broader debate over transparency in policing that took off this past decade with the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner in 2014, continuing well beyond the deaths of Brianna Taylor and George Floyd in 2020. Some cities, like Philadelphia in 2016 under then Police Commissioner Charles H. Ramsey, normalized the release of officer names amid the national call for more accountability.

Akron police auditor: Phil Young questions confidentiality agreement limiting what he can share

“It tells the public you have nothing to hide,” Ramsey, a former deputy chief in Chicago, told the Washington Post before retiring. “When you’re reluctant to release the names, it builds mistrust.”

“The name creates that true accountability,” Sheriff Joseph Lombardo of the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department also told the Post. “Once the name is put to the person or the act, it’s very hard for an organization to avoid the tough questions about that individual’s past.”

The Washington Post, which keeps a database of civilians and suspects killed by officers, examined 210 deadly encounters with police in 2015 and found that agencies across the country named officers 80% of the time.

Some departments, like the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department, withhold officer names at all cost.

Investigated and 'justified'

The officers involved in the most recent use of deadly force cases were reinstated to active duty within a month. But their actions remain under review until a grand jury of their peers in Summit County finds their behavior criminal or justified.

Though some cases have cost the city six-figure settlements, there have been no criminal charges filed against any of the 77 officers who've used deadly force in Akron since 2004, according to a Beacon Journal review.

In each of these 41 cases, the Summit County Prosecutor's Office found deadly force to be "justified" or grand juries declined to indict officers after reviewing evidence gathered by the Ohio Attorney General's Office.

Three of the 16 suspects killed in these 41 critical incidents were unarmed. A fourth suspect was shot in the back while running from police. Several suspects had a history of mental illness.

Six of the 77 officers were involved in two deadly force incidents. That's not uncommon as police say officers assigned to night shifts or SWAT details are more likely to find themselves in situations that result in lethal action.

John Turnure is the only Akron officer involved in at least three deadly force incidents. He resigned in 2021 while being investigated in a fourth use of force incident in which he shoved snow into a suspect's mouth while using his knee to pin the suspect to the ground.

Turnure was named before Akron police completed their internal investigation into the violent arrest.

'Officers have not been charged'

Clay Cozart, president of the Fraternal Order of Police in Akron, said officer safety should be the primary reason to withhold names.

The union president said a rise in violent crime coupled with difficulties in recruiting new officers would only lead to more situations of officers being forced to resort to lethal force to protect themselves and the public.

He said one officer was recently followed to their home after a shift while other officers have had their cars broken into. Cozart criticized activists in Akron who push for police accountability by publishing the name of officers in controversial cases before their actions are fully investigated.

Like uncharged suspects, officers who discharge their firearms should not be named until those investigations determine whether deadly force was justified, Cozart said .

"The officers have not been charged with a crime. They have not been found to have violated a policy. There is an investigation, but it's at the Attorney General's office," Cozart said. "And all of these (investigations by the AG's office) now are going to grand jury. Those proceedings are not made public until they finish with their investigation."

Reach reporter Doug Livingston at dlivingston@thebeaconjournal.com or 330-996-3792.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Akron refuses release of names in police officer involved shootings