Al Franken's Defenestration Is a Portrait of the Democratic Party

We should get the fundamentals out of the way first: whenever Jane Mayer writes anything for The New Yorker, attention must be paid. On Monday, she hit print and the pixels with a long piece on the defenestration of Al Franken. This is going to roil things up on the Intertoobz and across the electric Twitter machine for a while. Mayer paints a fairly damning portrait of a sadly typical Democratic bail-out on one of its own—not quite at the level of what happened to ACORN or Shirley Sherrod, but not dissimilar in those aspects in which the party flinched before it was hit. Mayer, who co-wrote a book that fairly well blew the whistle on Justice Clarence Thomas, never quite gets to why Franken resigned without the Senate Ethics Committee hearing that was his right, and that he had requested, but she does a good job establishing the political context within which the events unfolded.

What makes Mayer's reporting valuable is that it establishes the entire political context. Franken was coming off a series of bravura performances in his role in questioning many of Camp Runamuck's dubious hires during their confirmation hearings. It was largely his questioning that got eventual Attorney General Jeff Sessions ultimately to recuse himself from the investigation into Russian ratfcking. It was Franken who got Betsy DeVos to admit she knew nothing of the difference between proficiency and growth, a question so fundamental to education policy that even I, merely the son of a public school teacher, knew what Franken was talking about. And he put Neil Gorsuch on a spit during the latter's smug performance before the House Judiciary Committee. He had recently published a new book and there was more than a little talk about the possibility of his running for president in 2020. There were people in whose political and personal interest eliminating Franken from public life was considerable. As Mayer points out, Roger Stone seemed to have one of his ratfcking premonitions about what was coming, and the vast rightwing media apparatus seemed to be suspiciously well-prepared for the revelations.

Mayer is judicious in parceling out responsibility for the final outcome of this saga. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer comes across as rather feckless, while Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, on whom so many people place sole responsibility for Franken's fall that it arguably has hamstrung her long-shot presidential campaign, is portrayed not as a Machiavellian conniver, but as the leader of a group of women Democratic senators who were wrong-footed by the accusations while trying to maintain credibility in the face of accusations against the president* and against Roy Moore, the Gadsden Mall Creeper, who was running for the Senate in Georgia.

But the saddest—and most aggravating—passage in the piece is the collection of sad-faced second thoughts from former Franken allies who found it easier at the time to consider Franken an inconvenience that could be easily dispatched.

A remarkable number of Franken’s Senate colleagues have regrets about their own roles in his fall. Seven current and former U.S. senators who demanded Franken’s resignation in 2017 told me that they’d been wrong to do so. Such admissions are unusual in an institution whose members rarely concede mistakes. Patrick Leahy, the veteran Democrat from Vermont, said that his decision to seek Franken’s resignation without first getting all the facts was “one of the biggest mistakes I’ve made” in forty-five years in the Senate.

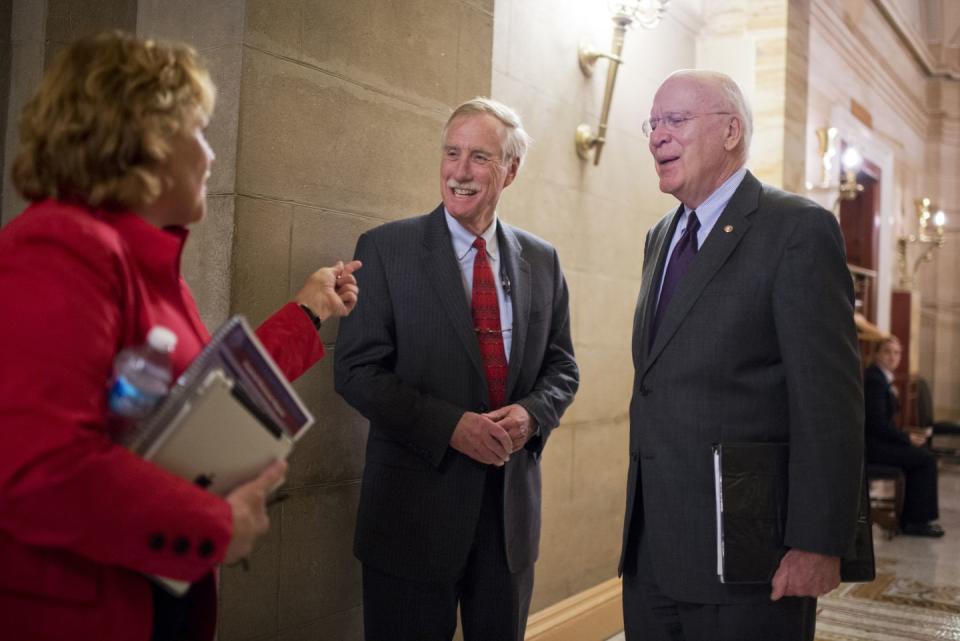

Heidi Heitkamp, the former senator from North Dakota, told me, “If there’s one decision I’ve made that I would take back, it’s the decision to call for his resignation. It was made in the heat of the moment, without concern for exactly what this was.” Tammy Duckworth, the junior Democratic senator from Illinois, told me that the Senate Ethics Committee “should have been allowed to move forward.” She said it was important to acknowledge the trauma that Franken’s accusers had gone through, but added, “We needed more facts. That due process didn’t happen is not good for our democracy.” Angus King, the Independent senator from Maine, said that he’d “regretted it ever since” he joined the call for Franken’s resignation. “There’s no excuse for sexual assault,” he said. “But Al deserved more of a process. I don’t denigrate the allegations, but this was the political equivalent of capital punishment.”

Senator Jeff Merkley, of Oregon, told me, “This was a rush to judgment that didn’t allow any of us to fully explore what this was about. I took the judgment of my peers rather than independently examining the circumstances. In my heart, I’ve not felt right about it.” Bill Nelson, the former Florida senator, said, “I realized almost right away I’d made a mistake. I felt terrible. I should have stood up for due process to render what it’s supposed to—the truth.” Tom Udall, the senior Democratic senator from New Mexico, said, “I made a mistake. I started having second thoughts shortly after he stepped down. He had the right to be heard by an independent investigative body. I’ve heard from people around my state, and around the country, saying that they think he got railroaded. It doesn’t seem fair. I’m a lawyer. I really believe in due process.”

Former Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid, who watched the drama unfold from retirement, told me, “It’s terrible what happened to him. It was unfair. It took the legs out from under him. He was a very fine senator.” Many voters have also protested Franken’s decision. A Change.org petition urging Franken to retract his resignation received more than seventy-five thousand signatures. It declared, “There’s a difference between abuse and a mistake.”

The last thing anyone needs right now is to re-litigate this matter, but Mayer provides an essential explanation for how and why a Democratic senator who was only then beginning to realize his potential was gone as quickly as he was. (The scenes of Franken's padding around his apartment are sadly reminiscent of how quickly Gary Hart became a non-person within the Democratic Party, depriving it of one of its most thoughtful and innovative voices.) Jane Mayer's great gift in recent years has been to explain how politics works in these very strange times. Whatever you may think of Al Franken, this is surely of a piece with that.

Respond to this post on the Esquire Politics Facebook page here.

You Might Also Like