Alabama Is Quickly Discovering the Dangers of Defying the Supreme Court

Alabama Republicans’ brash defiance of the Supreme Court hit a wall on Tuesday when a federal district court declared that the state’s new congressional maps discriminate against Black citizens in violation of the Voting Rights Act. The decision was entirely predictable given that GOP lawmakers have openly refused to draw districts that comply with the Supreme Court’s recent ruling against them. But the opinion is still remarkable for its caustic and exasperated criticism of the state’s legislative leaders for their perfidious yet bumbling efforts to evade a court order. The court’s exhaustive 196-page decision not only shoots down the new, racist maps, but also adds a new layer to the case: This dispute is now largely about the federal judiciary’s authority to enforce its own decisions against states dead-set on eviscerating the voting rights of their Black residents. If Alabama appeals to SCOTUS, the justices will notice this shift. And whenever a state legislature challenges the Supreme Court’s power, you should never bet against the court.

Alabama has ruthlessly attempted to undermine the political power of racial minorities since the end of Reconstruction in 1876; the sad truth is that, in 2023, Black Alabamians have not truly acquired equal citizenship in the state. Its state constitution remained an explicitly racist document designed to preserve “white supremacy,” including Jim Crow and slavery until last year, when voters finally replaced it. No Black Alabamian has won a statewide election since Reconstruction. And in 2021, white Republicans exploited their stranglehold on the Legislature to gerrymander racial minorities into a permanent minority. Although the state is nearly one-third Black, the Legislature’s 2021 maps gave Black voters a majority in just one of seven congressional districts. As a result, white voters controlled 86 percent of congressional districts, while only 65 percent of the state’s population is non-Hispanic white.

Voting rights advocates filed suit against this redistricting plan, alleging a violation of the Voting Rights Act. That law includes a requirement, known as Section 2, that racial minorities maintain equal opportunity to elect representatives of their choice. In January 2022, based on long-standing precedent, a right-leaning district court sided with the plaintiffs and ordered the state to draw a second “opportunity” district “in which Black voters either comprise a voting-age majority or something quite close to it.” (These cases are heard by three judges sitting on a district court, and this panel included two Donald Trump appointees.) The Supreme Court affirmed that decision in June in Allen v. Milligan, a 5–4 opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts, joined by Justice Brett Kavanaugh and the liberals. Roberts went out of his way to endorse every aspect of the district court’s opinion, including its mandate for a second “opportunity” district controlled by Black voters.

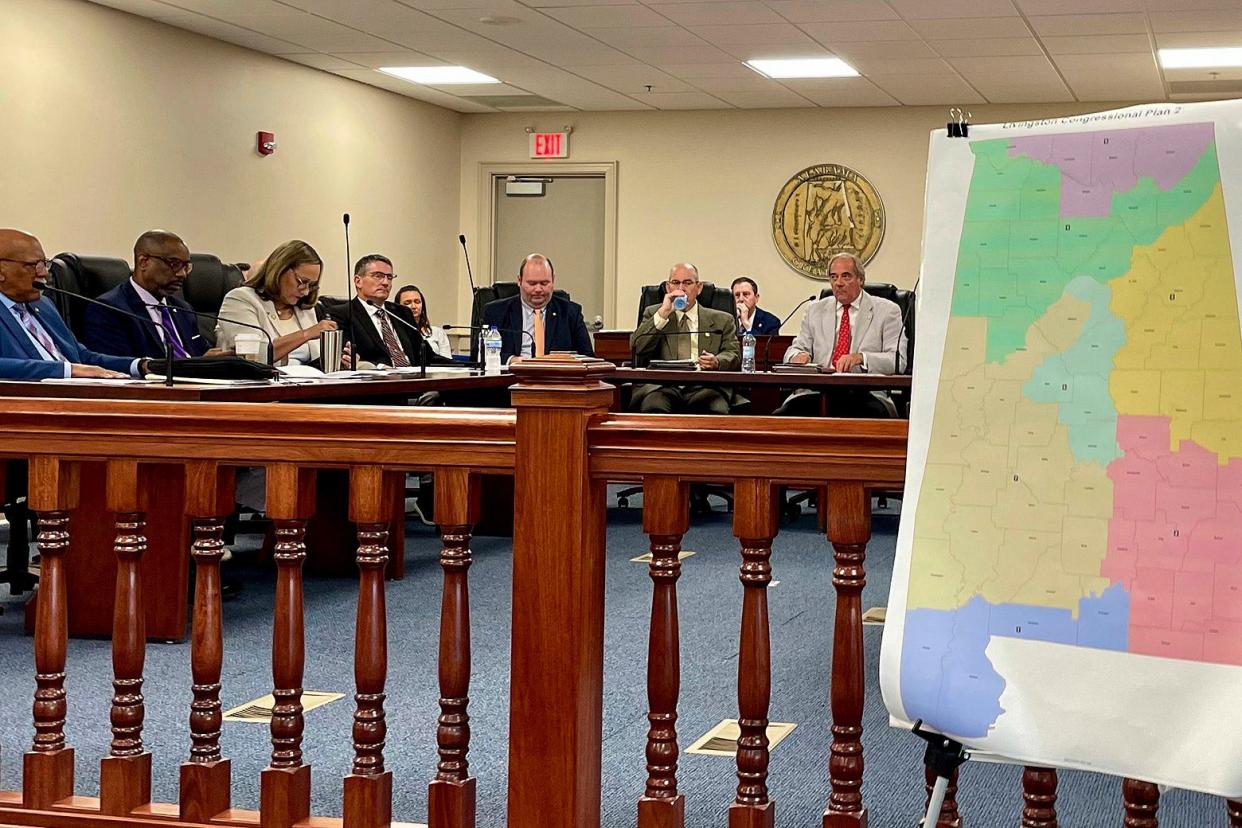

Alabama Republicans, however, treated the Supreme Court’s ruling as a mere suggestion. After a pointless delay, the Legislature enacted a map that contained the same flaws as the old one. Its new “opportunity” district did not give Black voters a majority “or something quite close to it,” as the district court had called for and the Supreme Court had endorsed. Instead, Black Alabamians make up just under 40 percent of the district’s voting-age population. Of course, 40 percent is not a majority, nor is it “quite close to” a majority under the Supreme Court’s voting rights precedents. GOP House Speaker Nathaniel Ledbetter gave the game away when he explained that “the Supreme Court ruling was 5–4, so there’s just one judge that needed to see something different.” His goal was not to draw a lawful map, but to peel off a conservative justice from the Supreme Court majority. Indeed, he and his colleagues did not even claim to follow the court’s order. They simply insisted that their new map restarted the entire legal process, erasing the court’s past analysis and forcing it to begin again from square one.

The district court did not agree. “We are deeply troubled,” it declared on Tuesday, “that the state enacted a map that the state readily admits does not provide the remedy we said federal law requires. We are disturbed by the evidence that the state delayed remedial proceedings but ultimately did not even nurture the ambition to provide the required remedy. And we are struck by the extraordinary circumstance we face.” Never before, the court noted, has a state submitted a revised redistricting plan that, by the state’s own admission, fails to comport with a previous order. Somehow, decades after the racist reign of George Wallace, we are in uncharted waters when it comes to racist voter suppression in Alabama.

Again, Alabama’s chief argument at this stage is that every time the Legislature redraws a map, courts must throw out their prior analysis and restart the case afresh. Moreover, according to the state, courts must permit elections under the challenged plan while mulling each redrawn map. And if a court strikes down a new map, it must put its ruling on hold for any upcoming races. It must also wait for the Legislature to draw a substitute map before imposing its own, even if the Legislature drags its feet in a bid to run out the clock to the next election.

The court found this position not just unpersuasive, but unconstitutional. “The state’s view,” it proclaimed, “is inconsistent with the Article III judicial power because it allows the state to constrain (indeed, to manipulate) the court’s authority to grant equitable relief.” Alabama seeks to create “an endless paradox that only it can break, thereby depriving plaintiffs of the ability to effectively challenge and the courts of the ability to remedy.” States cannot transform voting rights litigation into an “infinity loop” that only they may stop.

Then, just to drive in the ax, the court went ahead and assessed the new map from “ground zero anyway.” It easily concluded that, like the previous plan, these districts violated the Voting Rights Act by denying Black citizens an equal shot at electing their preferred representatives.

There were other digs along the way. Last time around, the court found that the testimony of Alabama’s “expert” witness, Thomas Bryan, was not credible, but rooted in errors, confusion, and “odious” race stereotyping. This time, “it is as though our credibility determination never occurred,” the court wrote. “The state repeatedly cites Mr. Bryan’s opinions but makes no effort to rehabilitate his credibility.” Alabama’s attempt to smear the Voting Rights Act as unconstitutional racism fared no better. The state claimed that protecting Black voters would amount to “affirmative action in redistricting” that violates the equal protection clause. It even suggested that the district court’s own order could run afoul of equal protection by, in essence, overprotecting Black citizens.

Here, Alabama was trying to channel Kavanaugh’s musing that, like affirmative action, “race-based redistricting” must have an endpoint—which, the state says, is right now. In its blundering effort to raise this argument, though, the state wound up accusing the district court itself of racism. And so, in yet another way, Alabama Republicans made this case about the judiciary’s own power to enforce the Voting Rights Act rather than a legal quarrel over the law’s scope. As the Supreme Court made clear in a different election case last term, it does not look kindly upon state legislatures that question such judicial authority.

The district court closed out its opinion by directing a nonpartisan, court-appointed special master to draw, at long last, a congressional map that complies with the Voting Rights Act by including two “opportunity” districts controlled by citizens of color. Alabama will probably ask the Supreme Court to intervene; its odds of success appear slim.

The state has pivoted to a strategy of bashing the very district court that a majority of justices already affirmed in full. It has turned this case into a referendum on the federal judiciary’s ability to enforce federal voting rights law—in essence, an assault on the Constitution’s supremacy clause itself. Roberts, Kavanaugh, and the liberals may not all agree on the precise contours of the Voting Rights Act. But they are united in their certainty that their decisions, not the gripes of some supercilious state legislators, are the law of the land.