Alan Bliss: When Capt. Eads came to town, he changed a river's course, city's history

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

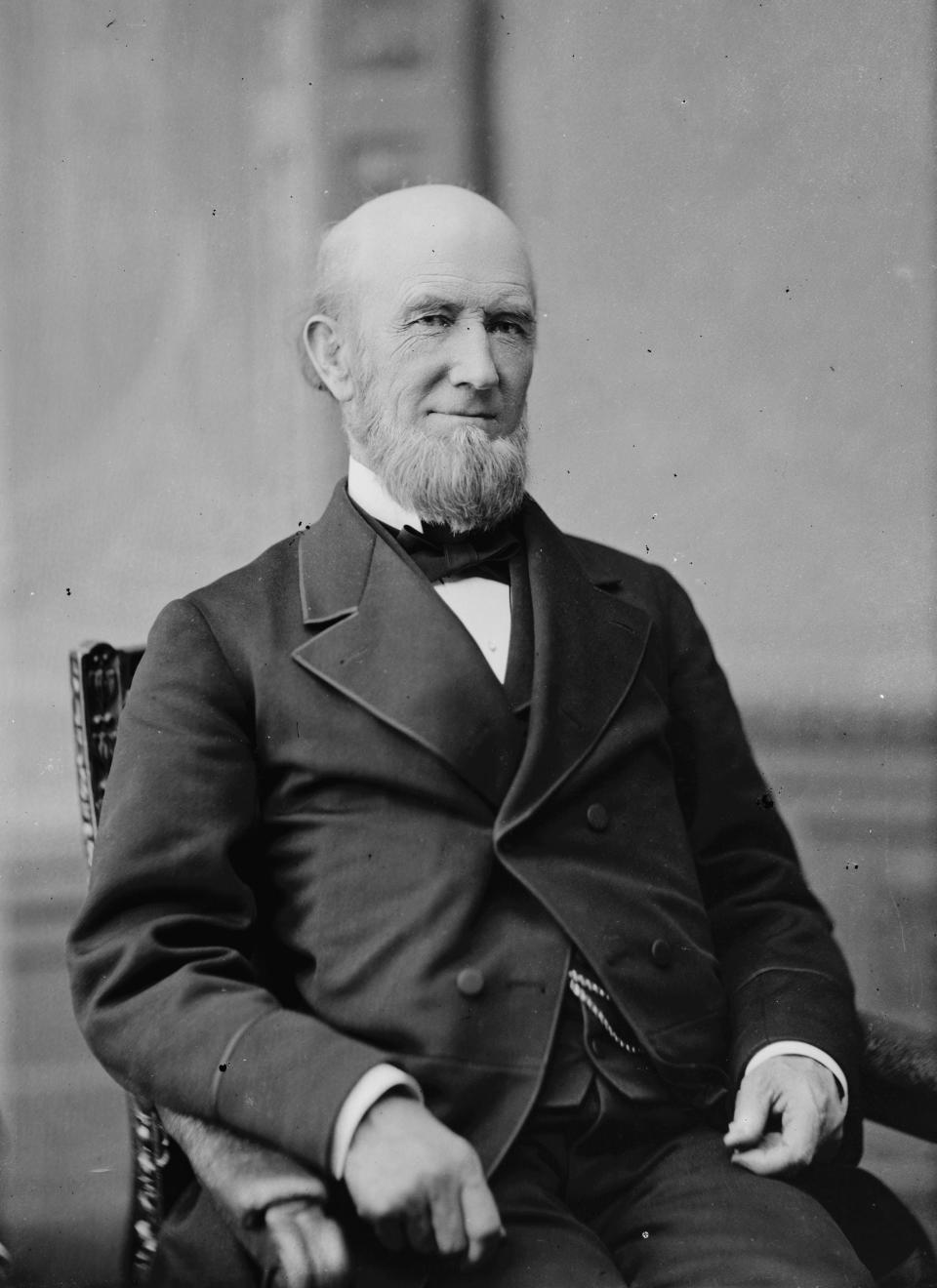

To students of engineering, the name of James B. Eads (1820-1887) is instantly recognizable. To the people of St. Louis, he is the namesake of the famous Eads Bridge, the first to connect the banks of the Mississippi River anywhere south of its junction with the Missouri River.

Completed in 1874 and more than a mile long, the bridge was Eads’ crowning achievement, bringing fame to him and to St. Louis. Today, 149 years later, the Eads Bridge is on the National Register of Historic Places and continues to carry automobiles, trucks and commuter rail service across the broad, fast-flowing Mississippi.

Nearly 1,000 miles from St. Louis, the town of Port Eads — in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana — also came to celebrate Capt. Eads. He was asked to create a design that answered the problem of endless silting of the river below New Orleans, stranding ships and closing the river to navigation.

Alan Bliss: Local boatbuilder sailed through the Roaring '20s on a sea of illicit booze

Mark Woods: What's 4,654 feet long, 12 feet wide and has people waiting to see it? The new Fuller Warren bridge path

Letters: Pending legislation can help pets (and their humans) benefit from telemedicine

Largely self-taught as an engineer, in 1876 the innovative Capt. Eads called for a pair of jetties to narrow and speed up the flow of water, forcing it to scour sediment from the bottom and cut its channel deeper.

So confident was he of his solution that he proposed to the federal government to build it for free, with the promise that if it succeeded, he would receive $8 million. Within months of their construction, Eads’ jetties performed as intended, opening the lower Mississippi to safe navigation by seagoing ships. A century later, the American Society of Civil Engineers named the jetties at the South Pass as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.

In February 1878, Jacksonville Mayor W. Stokes Boyd and a committee of concerned citizens contacted Eads, seeking his advice about a similar problem at the mouth of the St. Johns River. There, navigation had always been dangerous because of a patch of everchanging shoals covering 3 square miles, generally called the St. Johns Bar. Even with the local knowledge and skill of St. Johns Bar pilots, operating from Fort George Island, seagoing vessels had to wait, sometimes for days, to cross the bar.

Shipments moved unreliably and maintaining scheduled steamship service to Jacksonville was impossible. Jacksonville’s civic and business leadership had lamented “the impediment which exists directly at the mouth of the St. Johns.” They blamed the St. Johns Bar for strangling the prosperity of Jacksonville and all of Florida served by the river and its tributaries, for nearly 600 miles. Since the early 1850s, Dr. Abel S. Baldwin, a prominent physician, legislator and entrepreneur, had led lobbying efforts on behalf of Jacksonville to persuade the U.S. Congress to create a channel to the ocean.

By the late 1870s, Baldwin and the committee turned to the famous Capt. Eads for help.

Eads responded promptly, traveling to Jacksonville in order to personally examine the river mouth and surrounding area. Within a few weeks he was satisfied, and on March 29, 1878, he submitted his 23-page report to Mayor Boyd, giving us a fascinating snapshot of data and observations of the lower St. Johns, at nearly the last moment before it changed forever.

The conditions prevailing at the entrance to the St. Johns were very different from those of the Mississippi. Rather than river-born sediment, the St. Johns Bar resulted from the littoral current sweeping sand south from the Fort George Inlet and points north. The inlet, for its part, drained a broad tidal wetland behind the Talbot Islands, exerting powerful hydrodynamic forces at its inlet.

Despite natural forces different from those at the mouth of the Mississippi, the solution he had designed there would open the St. Johns as well. Eads proposed building two parallel stone jetties, each about 1.75 miles in length and reaching about 2 feet above mean high tide. The initial cost of materials, in 1878 dollars, he reckoned at $1,717,050, or about $52 million in 2023. The result, Eads predicted, would be a reliable shipping channel of at least 20 feet in depth at high tide.

'Untouchable': The Swilcan Bridge was restored after an outcry. What other golf landmarks shouldn't be touched?

Eye on erosion: 'Emergency berm' helped St. Johns beaches during Ian, Nicole; now new beach project possible

Congress, evidently convinced of the value a channel would add to economic development, appropriated its first $125,000 to the project in 1880, and work began the following year.

Constructing and paying for the Mayport jetties continued over the following decades. It is a story of human ingenuity, immensely hard work and even more immense amounts of money. The consequences of creating a man-made channel at the north of the St. Johns demonstrate the long historical reach of changing the natural environment, with impacts that are even now still being measured as far upriver as Palatka.

Other seaport cities sometimes name their important shipping channels for influential people. In Tampa, for example, there are the Garrison and the Sparkman channels. For whom might Jacksonville name its most important single feat of engineering, the channel connecting the St. Johns River to the Atlantic Ocean? Its designer, James Eads, or its leading advocate, Abel Baldwin? Perhaps the Congressional Channel, for the body that voted to pay for it, or the American Taxpayer Channel, for the financial underwriters?

Without the jetties and all that derived from their placement in the late 19th century, Jacksonville as we know it in 2023 would be different in nearly every imaginable way. Rather than being home to a major U.S. Navy base, for example, Mayport today might more closely resemble Jekyll Island, and downtown Jacksonville might have grown similarly to Palatka.

Conjuring historical “what ifs” can be amusing, but the value of reflecting on those forks in the road of human experience is that they help influence us, in the present moment, to consider our choices with the future in mind. That’s how the practice of history strengthens citizenship, and that is why there is a Jacksonville Historical Society.

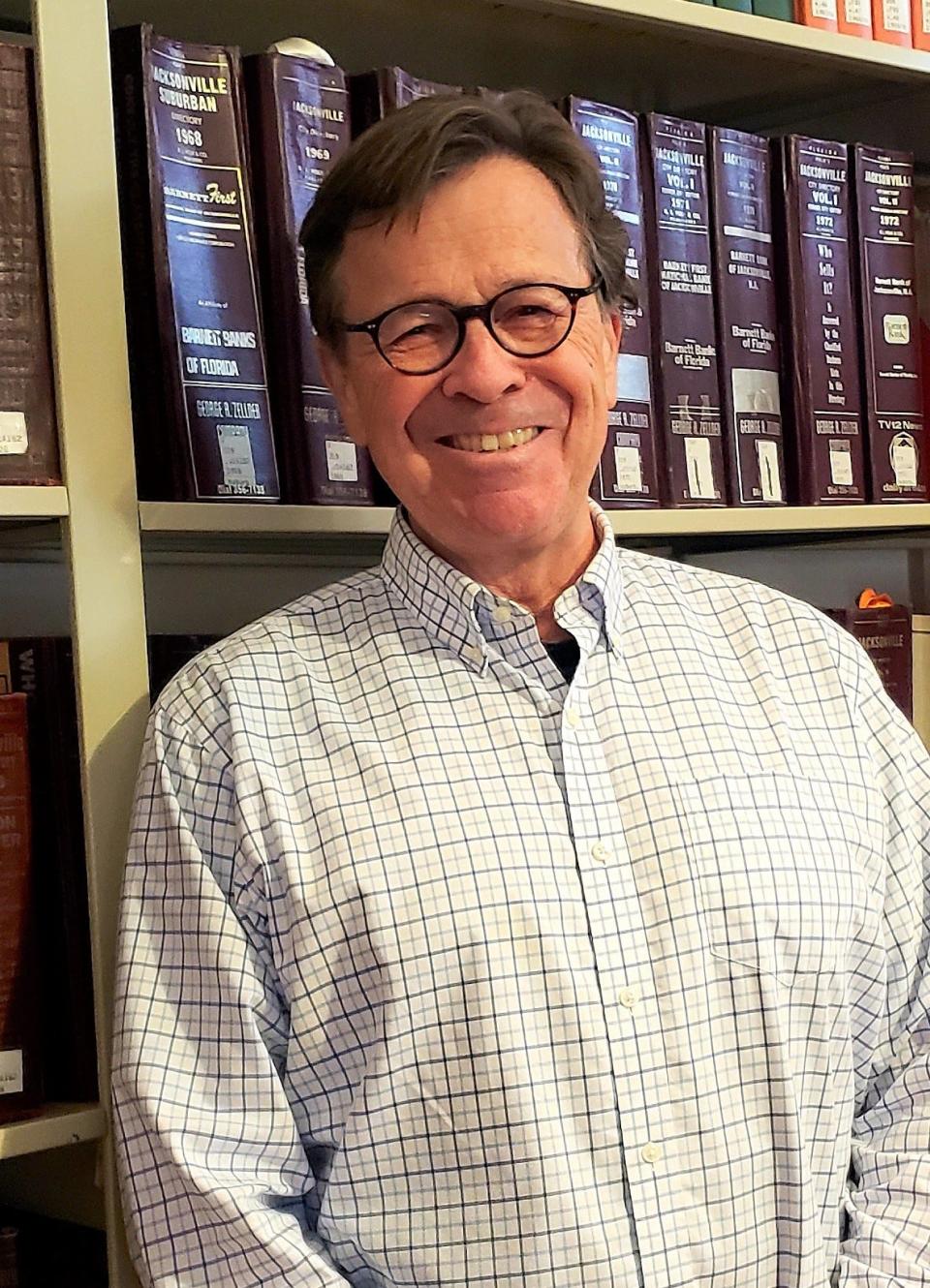

Alan J. Bliss, Ph.D., CEO, Jacksonville Historical Society

This guest column is the opinion of the author and does not necessarily represent the views of the Times-Union. We welcome a diversity of opinions.

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Capt. James Eads changed the St. Johns and local history, too