Alan Bliss: Local boatbuilder sailed through the Roaring '20s on a sea of illicit booze

From the end of the Great War until the beginning of the Great Depression, America experienced years that came to be known as the Roaring Twenties. It was a tumultuous decade that lastingly influenced the minds of those who lived through it. A century later, from our perspective in the 2020s, those may seem to have been simpler times.

People were less divided, but as usual, the truth is complicated. In science and technology, faith and culture, politics and race, business, finance, commerce and international affairs, the Twenties were dazzling and disruptive.

The most dramatic example was the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which empowered the federal and state governments to prohibit the production, sale and transport of “intoxicating liquors.” Florida had already adopted such a law in 1919, before Congress passed the National Prohibition Act.

Alan Bliss:Old sailing journals offer a glimpse of Jacksonville’s maritime past

The battle for booze:Bootleggers were big business in the woods and swamps of Northeast Florida, in Prohibition and beyond

Informally called the Volstead Act, it was one of the defining moments of the decade — indeed, making alcohol illegal put the “roar” in the Roaring Twenties.

While 46 of the 48 states ratified the 18th Amendment, the new law was deeply divisive. Some had long and fervently hoped and campaigned to make alcohol illegal. Others were indifferent, but a great many Americans resented the law. Soon enough, resentment turned into resistance.

Banning anything only increases its allure, and supplying those who still enjoyed their beer, wine and spirits soon became a major underground industry. Opportunities for profit attracted business people regardless of their attitudes about alcohol. Smuggling, an American tradition since colonial times, drew resourceful entrepreneurs into what many saw as harmless criminality.

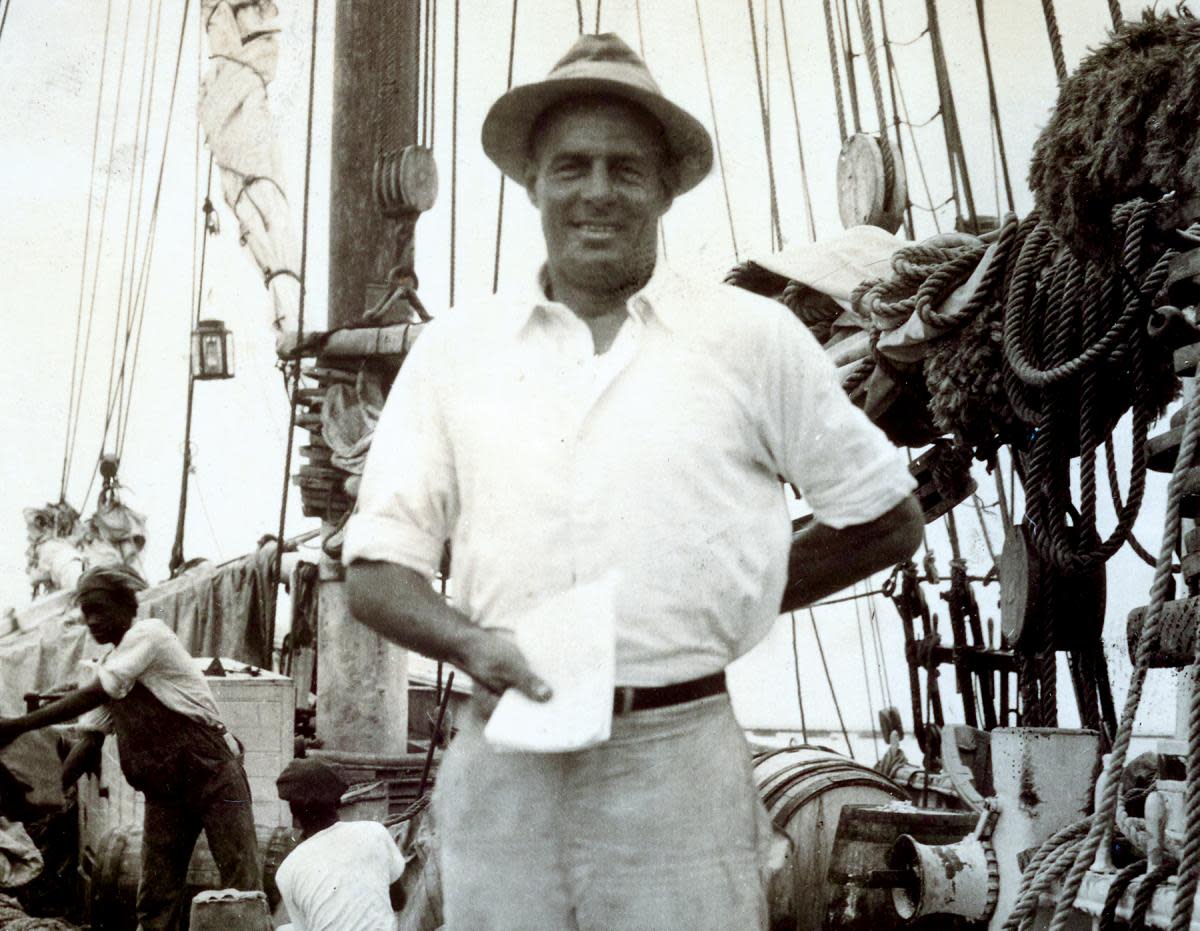

One of the most famous was a Florida boatbuilder named William “Bill” McCoy. Along with his brother, Ben, Bill McCoy had been operating a motorboat service between Jacksonville and the rich oceanfront communities to the south. An experienced sailor, McCoy was invited to sail a decrepit schooner to the Bahamas and back, returning with a cargo of imported liquors.

Impressed by the amount of money offered, but wary of the condition of the vessel, McCoy instead financed the purchase of his own schooner and in February 1921 set sail from Jacksonville to Nassau on his first smuggling voyage.

That first trip turned into semi-comedic chaos. In Nassau, the amused Bahamians loaded McCoy’s boat with cases of Scotch, gin and other premium spirits. With false clearance papers indicating that his cargo was bound for Canada, Captain Bill sailed across the Gulf Stream ahead of a raging gale, navigating blindly toward a pre-arranged landing site along the Georgia coast, south of Savannah.

After nearly running his vessel ashore in the pitch darkness, McCoy hove to, and by the dim light of dawn, navigated through the inlet into St. Catherines Sound amidst surf crashing ashore alongside him.

Anchored in the protected lee of St. Catherines Island, McCoy’s crew unloaded their delicate cargo into a small craft, rested for a day and set sail once more for Nassau. Captain Bill found himself $15,000 richer for his efforts, and even though he was an uncommon sailor who never took an intoxicating drink, he was intoxicated by the prospect of wealth earned by adventure.

He scoffed at the laws against alcohol, but McCoy was scrupulously honest in his business dealings. By resisting the temptation to increase his profits by watering down quality liquor, he won a reputation for delivering legitimate goods. Buyers up and down the east coast of the United States came to trust his crews as the bearers of the undiluted brands, which is how his name became associated with goods called “the real McCoy.”

Eventually McCoy was caught, convicted and served time in prison, losing his ships and most of his wealth. Prohibition endured until 1933 and passage of the 21st Amendment. By then Bill McCoy had returned to Florida, claiming to regret nothing except that rum-running had become a tough business that rewarded violence and double-dealing. For those and other reasons, Americans had turned against Prohibition, which had indeed elevated organized crime far beyond its previous role in the underground economy. It had also elevated the role of local, state and federal government in the enforcement of laws at each level.

Jacksonville’s Roaring Twenties are a century past. People born in any year of that decade are now in their 90s, but they grew up hearing stories of those discontented years. If you are lucky enough to know a nonagenarian, ask them to share what they remember — they just may astonish you.

Alan J. Bliss, Ph.D., chief executive officer, Jacksonville Historical Society

This guest column is the opinion of the author and does not necessarily represent the views of the Times-Union. We welcome a diversity of opinions.

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Bill McCoy ran successful smuggling operation during Prohibition