Alan Bliss: The long historical reach of ‘redlining’ in Jacksonville and its ongoing effects

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Twice recently I have been asked to speak publicly about the history of “redlining” in Jacksonville. The interest may have to do with how closely our financial lives are tied to homeownership. Nearly two-thirds of Americans are homeowners and for them, the difference between their home value and their mortgage balance is the lion’s share of what they consider their wealth.

It was not always that way and the change began during the Great Depression. Until then, all mortgage lending was local. The modern financial infrastructure that makes homebuying possible for most of us did not exist. A very short list of innovations forced on the housing market by the Great Depression includes mortgage-backed securities, housing bonds, mortgage insurance, down payments of 20% (or less), 15-year loan terms (or longer), residential zoning laws and standardized appraisals.

Until the 1930s, buying a home required many years of accumulating cash for a down payment — typically 50% of the purchase price. Buyers unable to meet that threshold were treated as high-risk borrowers because if times got tough, they were more likely to stop making payments. The notoriously tight-fisted Ed Ball, longtime head of Jacksonville’s Florida National Bank, reportedly mandated a maximum loan-to-value ratio of 20% for FNB’s customers.

In addition to large down payments, home mortgages typically came with terms of five years or less. Then as now, it was nearly impossible to pay off a mortgage so quickly, but if the borrower kept up the payments and held a steady job, it was likely that the loan could be renewed for another term. However, during an economic downturn, all bets were off.

By the early 1930s, as a worldwide depression took hold, even those whose credit was good and who held a strong equity position in their home were likely to find it impossible to renew their loan. Foreclosures and homelessness soared.

Travis Williams: A new day dawns as Jacksonville's 'Out East’ rebuilds from within

2020 study: Years after redlining, Jacksonville's have-not neighborhoods suffer more in heat

Letters: If U.S. hesitant to support Ukraine, give them their nukes back

Beginning in March 1933, the new presidential administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt created a series of innovative programs to preserve America’s market economy. With respect to housing markets, their first innovation was the Home Owners’ Loan Corp. (HOLC). That agency’s purpose was to buy residential mortgages, freeing up capital for banks who were otherwise unable to make or renew loans. But which loans were safe to buy?

That’s where Residential Security Maps came into play.

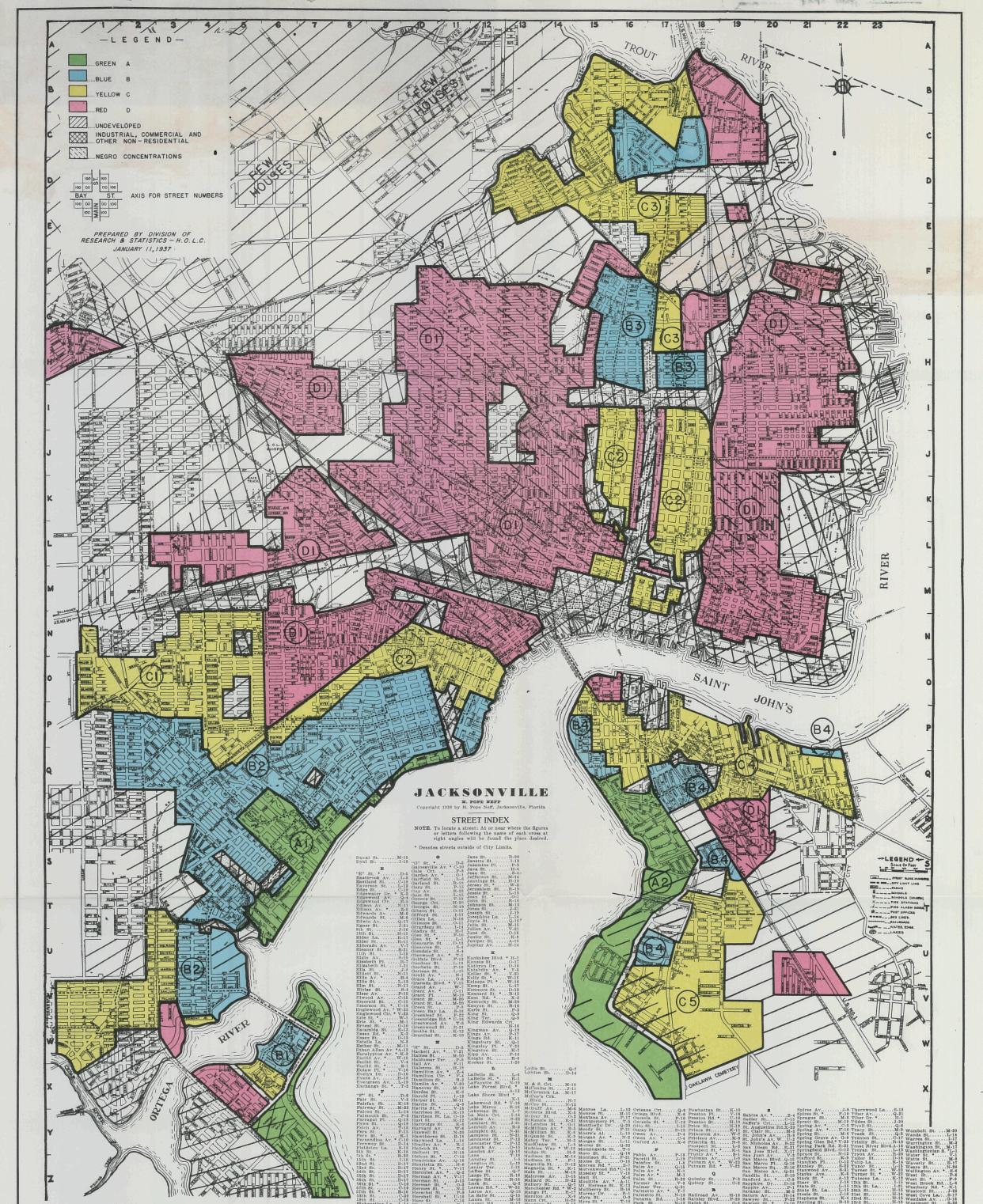

To guide the HOLC and later agencies, such as the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), local appraisers created maps of their cities. They identified neighborhoods according to what appraisers considered the level of lending risk. Appraisers and real estate agents viewed risk similarly, through the lens of things such as wealth, class, ethnicity and race.

The key to Jacksonville’s map is identical to those on the Residential Security Maps created for more than 200 cities across the United States, illustrating risk this way:

Green (A) — Newer, homogenous, in-demand;

Blue (B) — Reached its peak, but stability expected for some years;

Yellow (C) — In decline, racially or ethnically diverse; and

Red (D) — Hazardous, decline has already occurred.

Local appraisers had no need for maps to know the high-risk neighborhoods in their city — no one knows that better than appraisers and real estate agents. Instead, the HOLC’s maps allowed federal agencies and investors to evaluate loans according to their level of risk. Risk factors included such things as low elevation, poor construction quality and proximity to commercial or industrial uses.

They also included the identities of those already living there. The maps identified areas of “Negro concentrations,” as Jacksonville’s map shows, as well as narrative references to concentrations of Jews, Italians and other ethnic groups.

Over the decades since the maps were created, the data shows a pattern over time of lower investment in neighborhoods that were in the 1930s labeled as Red zones. Public investments in infrastructure suffered, which held down property values. People who owned homes there at the time (and those who came after them) found it harder to borrow money at favorable rates and terms, which further suppressed property values.

The opportunity for wealth-building through homeownership was reduced, just when the majority of Americans began to experience that opportunity in greater measure than ever before. Between 1940 and 2010, American homeownership grew from the low 40% range to nearly 70%, due mainly to federal reforms of the market for mortgage lending.

In America, homeownership has long been promoted, though unjustly, as a marker of citizenship and personal virtue. It is also a proven pathway to individual and family wealth building. But, in an example of the law of unintended consequences, the long chronological reach of old assumptions about class, ethnicity and race means that some Americans today enjoy fewer of the benefits of homeownership.

A glance at the 1936 Residential Security Map of Jacksonville helps to tell the story.

Alan J. Bliss, Ph.D., chief executive officer, Jacksonville Historical Society

This guest column is the opinion of the author and does not necessarily represent the views of the Times-Union. We welcome a diversity of opinions.

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Alan Bliss: The long historical reach of ‘redlining’ in Jacksonville