Alan Mills, face of Wimbledon tennis as the referee whose long career spanned Connors and McEnroe – obituary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

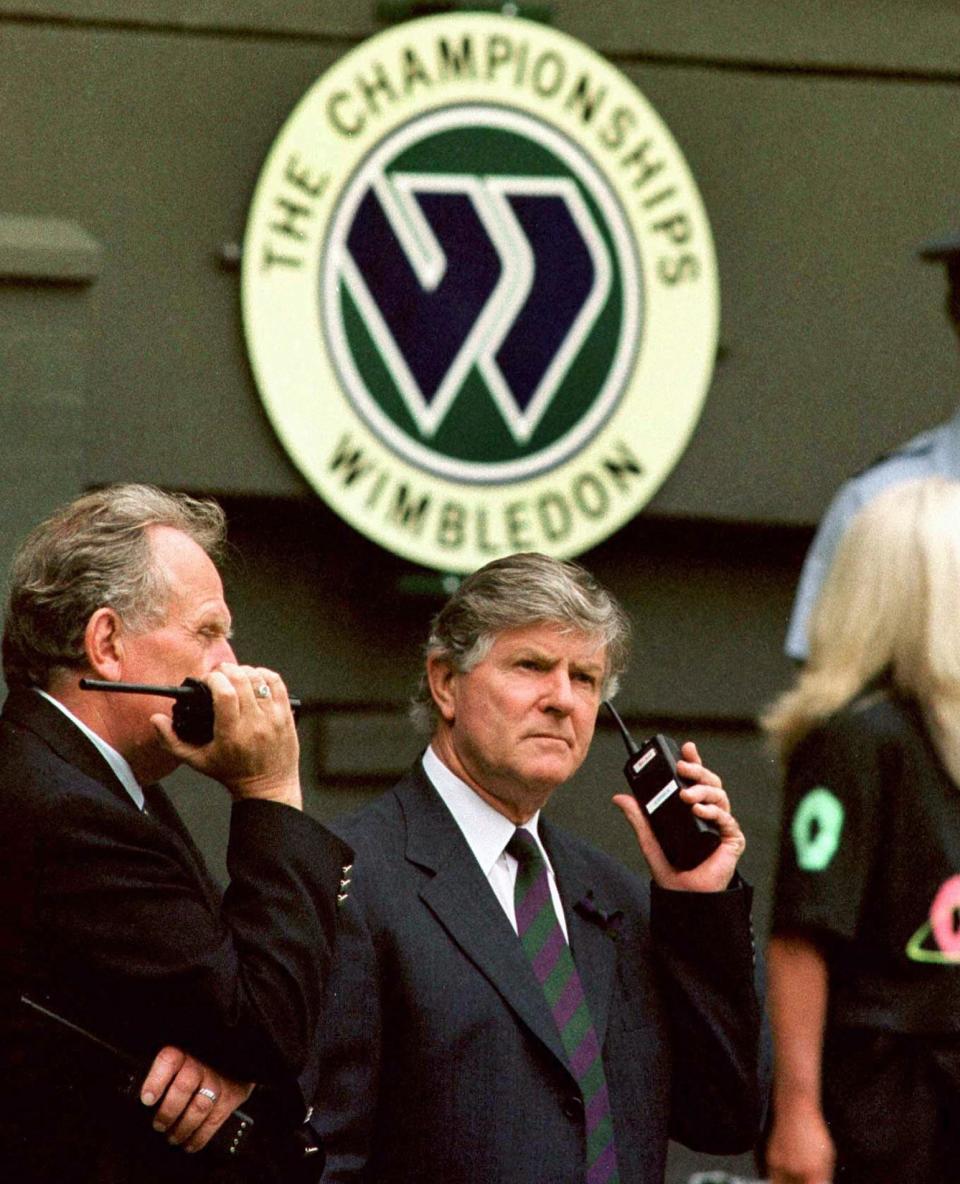

Alan Mills, who has died aged 88, was the public face of the Wimbledon tennis championships as its referee from 1983 to 2005.

Mills’s appearance on court, walkie-talkie in hand, usually signified one of two things: rain stopping play, or a tantrum thrown by one of the players.

As he himself put it: “To most members of the viewing public I’m the spoilsport in the grey suit who pops out of the corner to order the covers on, or to administer a rap over the knuckles to the men behaving badly. In truth, the vast majority of our hard work is done behind the scenes, juggling the interests of a host of different groups of people.”

His unseen duties included getting the following day’s order of play out as quickly as possible, to satisfy the requirements of the newspapers and television companies as well as of the players and their agents. It was often a struggle to find the right time and the right court for the right player.

With his office having to oversee around 700 matches in the course of the fortnight, bad weather could cause a bewildering backlog of matches. In 1985, in the first week, 27 hours of play were lost; in the second, the men’s semi-finals were disrupted by a thunderstorm which caused a flash flood in the grounds.

Another exceptionally wet year was 1991: by the first Thursday evening, only 52 of the scheduled 240 matches had been played; meanwhile, the strawberry crop in Kent had been ruined, and the fruit had to be imported from the Continent.

Mills was viewed by some members of the public as the appropriate target for their outrage when they had a complaint, and his in-tray was usually full. When players took to spitting on court, some spectators demanded the introduction of spittoons, one writing: “Dear Mr Mills, why don’t you give these bloody animals handkerchiefs?”

On another occasion a correspondent complained: “Dear Mr Mills, Why is it that every time I turn on my television, all I get is tennis, tennis, tennis and more tennis? I hate tennis. I demand that you refund me part of my television licence.”

Mills’s most visible task, however, was on-court discipline, and he took over the role of referee at a time when players were learning to express themselves in ways previously unseen.

Reflecting on his early days in the job, Mills wrote: “Until recently tennis had been a gentlemanly, relatively sedate sport when the winner would walk off with his arm around his opponent and buy him a drink or two in the bar afterwards.

“But since the late 1970s a different kind of animal had come to stalk the court, and once the barriers of good conduct had been broken down, this new breed had begun to stampede into the former bastion of civilised behaviour with a terrifying lack of embarrassment or shame.”

He attributed this change to the growing “clout” of the professional since the advent of the Open era in 1968: “With every nought added to the end of their prize money cheques came a proportionate rise in the amount of power the players felt was entitled to them.

“As far as many of them were concerned, some of the chair umpires and line judges were just doddery old amateurs who had left their day jobs for a free Wimbledon ticket and nice day in the sun. In certain cases they were right.”

Mills’s particular bugbears were John McEnroe, Jimmy Connors and Ivan Lendl, who had “effectively torn up tennis’s book of etiquette and given the green light to the younger players emerging in the game to start throwing their rackets around when the mood took them”.

His first bruising encounter with McEnroe came in his first year as referee, 1983. The American was destined to win the Championship for the second time, but in his second round match against Florin Segarceanu of Romania, McEnroe was foot-faulted, and reacted by telling the chair umpire: “You’re doing a wonderful job for someone who doesn’t know two plus two.”

The crowd was thrilled, particularly when the player threatened to walk off court, which would have meant automatically defaulting the match. Mills hurried to the court, and the match resumed. When McEnroe was foot-faulted again, he was able to confirm that the call had been correct.

At Queen’s the following year, a week before Wimbledon, McEnroe called the umpire a “moron”, and the All England Club felt it advisable to take out a huge indemnity with Lloyd’s against being sued by a disqualified played for loss of earnings.

Despite these problems, Mills was a huge admirer of McEnroe’s gifts (describing him as “certainly up there among the very greatest”). But he had less affection for Jimmy Connors, in his opinion “one of the most aggressive and intimidating individuals I have ever come across on a tennis court”.

In 1988, after losing in the singles, Connors stormed off court, swearing at the ground staff. “I was not overwhelmed with sadness to see him pack his bags and leave,” Mills observed laconically.

If the 1990s saw an improvement in the players’ behaviour, the 1995 tournament provided the two most controversial events of Mills’s career as a referee. In the first he had to disqualify Tim Henman, after the great British hope, in a moment of frustration during a men’s doubles match, took a ball from his pocket and smashed it with his racket, accidentally hitting a ballgirl in the face.

“It was not the most popular decision I have ever made at Wimbledon,” Mills said. Henman was the only player he ever had to disqualify.

As a former player himself, Mills understood the pressures the competitors were under. But his playing career had been in a more gentle era, and the closest he had ever come to an on-court rant had been to be ask an umpire: “Are you quite sure about that?”

Furthermore, his duty as referee was to ensure the smooth running of the event, and to try to avoid situations which would reflect badly on the Championships. From the outset Mills had decided that when a player received a second code violation during a match, he would head for the court: “It’s amazing what effect a man in a suit standing in the corner and his brow furrowed can have on the behaviour of players.”

Alan Ronald Mills was born on November 6 1935 at Stretford, Manchester. His father was a railway controller, his mother a railway clerk. He was educated at Waterloo Grammar School, near Liverpool, leaving when he was 16 to take up an apprenticeship as an electrical engineer in Southport.

At school he had played cricket and football for the 1st XI, but had not taken up tennis until he was 13. After he had won a local event, his headmaster marked out a court in the school playground and told the staff to rally with him in the lunch hour. His parents then took out a second mortgage to finance his participation in tournaments around the country.

He first met his future wife Jill Rook, a lively, attritional player, at the Surbiton tournament; they were engaged in 1957 but had to wait to get married until he had completed his National Service in the RAF. Like Mills she represented Surrey at County Week for years.

Between 1957 and 1966 Mills was ranked in the British Top 10, and he competed at Wimbledon for 17 years, twice reaching the last 16 of the men’s singles and making the semi-finals of the doubles in 1965. He also represented Britain in the Davis Cup, playing in four ties in all. Against Luxembourg, he became the only man to win his Davis Cup debut 6-0, 6-0, 6-0.

For 15 years Mills toured the world as an amateur, while earning his living as a sales representative for the soap manufacturer Cussons and subsequently for Dunlop. “I knew fairly early on in my career that I was never going to be one of the greats,” he recalled. “I was never defeatist, but I understood my limitations.”

He did, however, manage to beat Rod Laver, albeit at a pre-Wimbledon tournament at the Hurlingham Club; and in the first round of the 1959 Wimbledon singles he defeated the former champion Jaroslav Drobny, who was then past his best.

In 1966 Mills turned professional, a move which led to his being thrown out of the All England Club (in that era, no professionals were allowed to be members, but a year later he was granted honorary membership). He became the tennis pro at the Treasure Cay hotel in the Bahamas, and then spent two years at a tennis club in Ohio before coaching for a year at Millfield school in Somerset.

In 1969 he took over as professional at his local club, St George’s, at Weybridge in Surrey. In the early 1970s he was the national coach for Wales, and he also served as professional at the All England Club.

In 1976 he was invited to become an assistant referee at Wimbledon, moving to the top job seven years later and going on to referee at tournaments around the world until finally retiring in 2015.

Mills regarded Rod Laver as the greatest all-round player in the history of the game, and also reserved special praise for the seven-times Wimbledon champion Pete Sampras – “a delight to deal with; not once did he cause a dispute that I had to resolve”.

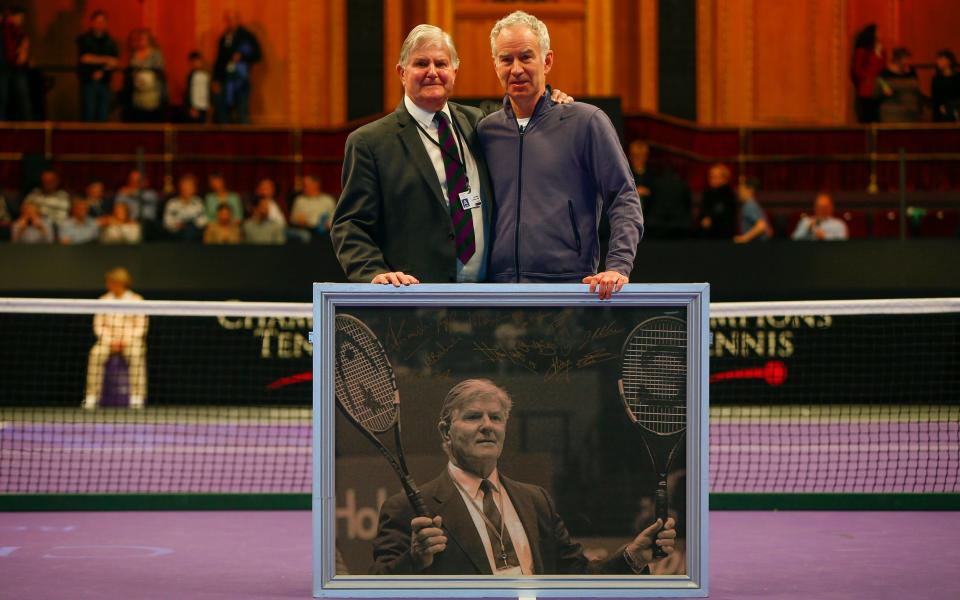

As for McEnroe, despite the on-court meltdowns of old Mills always retained his amused affection for the American. Late in life, he was watching a match between McEnroe and Pat Cash at the Royal Albert Hall. McEnroe was leading comfortably and Mills’s companion said: “It looks as though this should be over pretty quickly.” Smiling, Mills replied: “Not that quickly – McEnroe hasn’t yet had his contracted row with the umpire.”

Alan Mills was appointed OBE in 1996 and CBE in 2006. He published a memoir, Lifting the Covers, in 2005.

He married, in 1960, Jill Rook, with whom he played very good mixed doubles; she also represented England at table tennis. They had a son and a daughter.

Alan Mills, born November 6 1935, died January 18 2024