When Alexandra Fuller Meets Trouble, She Writes Her Way Out

The last few years have been really rough on Alexandra Fuller. The noted memoirist’s Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight and Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness were critically acclaimed accounts of her dysfunctional family and what it was like growing up on a farm in Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) during a time of civil war between white colonizers and the indigenous population. But Fuller lost her British-born father three years ago. Then, in quick succession, her sister stopped speaking to her, she broke up with her boyfriend, and her 21-year-old son died from complications of a brain seizure.

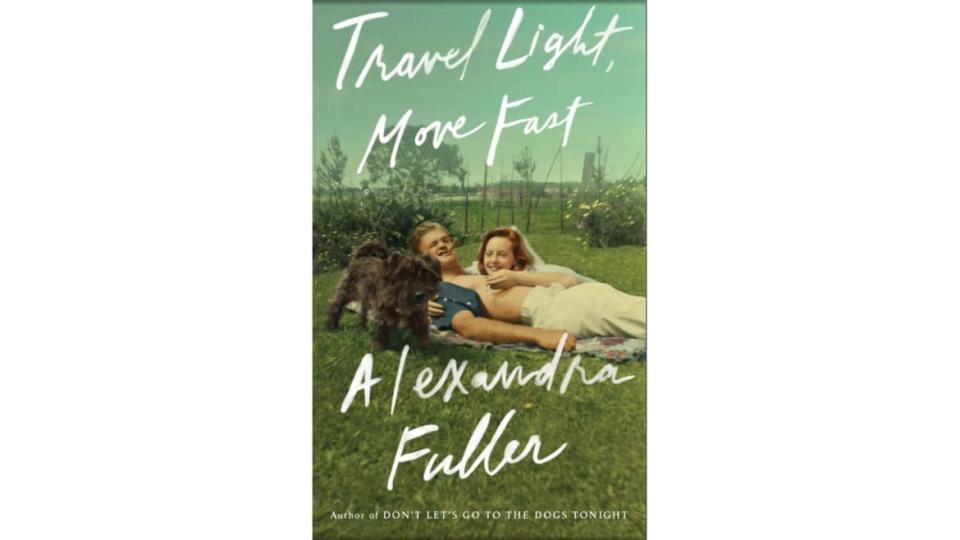

So naturally, Fuller decided to put all this pain in her latest book, Travel Light, Move Fast, a gut punch of a memoir filled not just with grief, but with stories about the war and incredibly entertaining tales of her larger-than-life dad.

“This is the vehicle for me to get to what I care about,” Fuller told The Daily Beast in a sit-down interview in Raleigh, N.C., during a seven-city tour promoting her latest book, when asked why she writes such crushingly personal books. “Which is what happens when you’re raised white supremacist, what happens when you survive war, when there’s incredible love, but also incredible dysfunction, which I think speaks to most white settlers in Zimbabwe and Zambia [where Fuller also lived]. Why not do it through a vehicle that people love? And it’s my tragedy, it’s what I think about.”

Surviving Wartorn Africa—And Divorce

Fuller’s latest begins with her father dying in a Budapest hospital, then bounces backward in time to talk about what he was like in life—a restless man who moved his family more than 20 times through four African countries, endured the deaths of three young children from drowning and meningitis, and was on the front lines during the 1964–1979 war that culminated in the creation of the majority-ruled state of Zimbabwe.

“When I was growing up, he was a soldier, he had been conscripted,” said Fuller, 50, who in person speaks rapidly, features a lively wit, is brutally frank, and has the weathered beauty of someone who has spent much of their life outdoors. “By the end of the war, he was fighting six months a year, and coming home in between. He was someone I admired, he was god-like to me, but he was authoritarian. As I got older, and he became more essentially himself and dissolved the war out of him, the person he essentially was, was allowed to bubble up, and he was delightful.”

That certainly seems to be the case, if the numerous examples of her father’s one-liners scattered throughout the book are any indication. A heavy smoker, if he offered anyone a cigarette, he’d ask if they wanted a “lung snack.” “I’ll try anything once,” he used to say, “except buggery, incest, and moderation.” And, explaining his hatred of luxury and his sometimes slovenly lifestyle in the African bush, Fuller’s father once said, “I find luxury only encourages guests to overstay their welcome. A reptile or two keeps everyone on their toes.”

All this is certainly entertaining, but Fuller doesn’t shy away from putting it in a much harsher context: how growing up in a world of white colonial racism affected her and her family, an experience she sees as thoroughly abusive. “We were put on the front lines of a civil war that was a racial civil war,” she said, “a war for white minority rule. I don’t know how much more racist you can get. We weren’t in a compound in northern Idaho, but we may as well have been. It’s very abusive to be raised racist. It’s a lot to undo, and that’s your job. My whole education, my whole religious upbringing, my family of origin, it was all racist. And it was the job of the child to undo it. That’s amazingly abusive.”

Given this brutal honesty, it comes as no surprise that Fuller’s family hates her books and has asked her to stop writing them. But, she says in her latest, “I can’t look away.” This willingness to reveal her family’s, and white Africa’s, dirty laundry, might also be a significant reason why her sister Vanessa no longer talks to her.

“I had a much more happy childhood” than her, said Fuller. “I loved the horses, I loved the books [her mother encouraged a voracious reading habit], I was in love with the farms [they lived on]. And Vanessa really wanted to live in a cottage in England and not have this complicated issue of me bringing up all this stuff. I think the books became the reason, but if it hadn’t been the books, I think she would have found another excuse.”

Married to, and now divorced from, an American, Fuller has lived in the States for over 20 years, first in Wyoming, now Idaho—near, she says, the area where another bestselling memoirist, Tara Westover of Educated fame, grew up. “Whenever I’m writing, I have one eye on the land that I left, and one eye on the land that I’m in,” she told the Beast. “They feel remarkably similar to me. It’s like Rhodesia in 1977, when you start getting nationalistic and start to worry about women’s fertility, and when God becomes weaponized.”

But even thousands of miles away, her African roots are still very close, no more so than the way in which she has dealt with death. Raised basically by members of the indigenous community in Rhodesia because her parents were so involved with making a living and fighting a war, “as life and death happened, the people who explained it to me weren’t my parents,” she said.

“It’s very different, because your ancestors don’t leave you; they’re living in the trees, it’s this lively communication with the dead at all times, it’s not this end [as in Western culture] at all. And the way in which you’re not expected to deal with it on your own; there’s community. All the big things—life, death, birth, parenting—are learned from [Africa].”

So as she explains it, “to lose your father is to lose your history, and to lose your son is to lose your future, so you’re stuck in the very unpleasant now. When your father dies, your job is to become the elder that he was. When your son dies, your job is to become the mother of an ancestor, and I think that is very rigorous. Being raised in an indigenous community gave me an idea of what that looked like.”

Still, Travel Light, Move Fast (one of her father’s pieces of advice) ends on—take your pick—either the bleakest of notes, or a feeling that things are bound to get better. “I am nowhere now, and it’s a start,” says Fuller in the book. But then she adds that her dad would tell her “it’ll be all right in the end.”

But, adds Fuller, “if it’s not all right, it’s not the end.”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.