Allen University promised to fix historic home of its past president. Now, it wants to tear it down

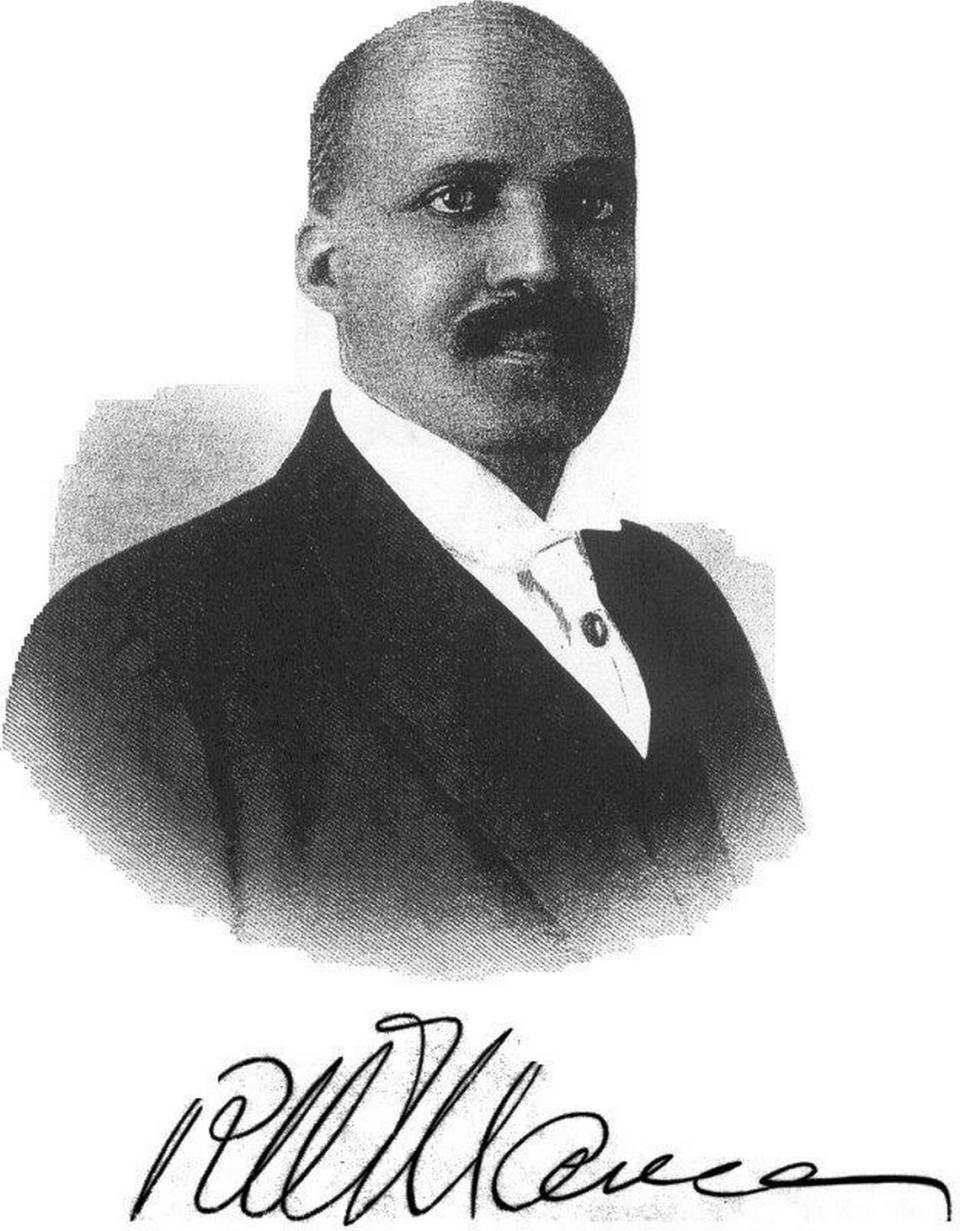

About 100 years ago, Robert Weston Mance moved into a two-story, American Foursquare frame house on Pine Street in a Columbia neighborhood famous for Black success.

Mance was the president of the historically Black Allen University from 1916-1924. His father was a charter trustee of the institution. His son, who remained in the Pine Street home until 1957, was a civil rights activist and superintendent of Columbia’s Waverly Hospital.

Today, the property is affectionately called “The President’s House” and formally called the Robert Weston Mance House, and it has remained both a link to Allen University’s past and an homage to the Black leaders who once called it home.

Fifteen years ago, the university promised to rehabilitate the storied home. Now, it wants to tear the house down.

Neighbors and historic preservationists have decried the effort, arguing the university would be stripping the community of an important piece of history. A city of Columbia review board has already denied the university’s request for the demolition.

Allen officials have said restoring the property could cost more than $500,000 and are taking the issue to court.

A back and forth

Members of Columbia’s Design/Development Review Commission in February rejected Allen University’s request to demolish the 120 year old house.

That hearing came months after the university had already begun an illegal demolition. In August, neighbors reported a wrecking crew at the property. The city intervened, but not before the wrecking crew started tearing the roof down.

Still, city preservationists determined the house had good bones.

“While the building has suffered damage from years of neglect, preservation staff agreed that it appeared to be structurally sound and was not in as severe a state of disrepair as many historic buildings that we visit,” city staff wrote in a report to the design commission after a visit to the site.

The design commission ruled the property could still be saved and, given its historical significance, should not be destroyed.

Representatives from Allen who attended that meeting argued that the restoration would be expensive, saying one firm told them it would cost more than $500,000 to rehabilitate the house.

“Allen University isn’t in the Waverly district to hurt it, but we have to make decisions that are applicable to the university,” Eric Gamble, Allen’s vice president of planning and information technology, told DDRC members in February. Gamble also explained that the school’s CEO and board of trustees had voted to demolish the property.

At the same meeting, Waverly neighborhood leaders and Allen alumni decried the attempt, saying it would only further strip Columbia of already dwindling pillars of Black history.

“In a time when Black history is trying to be whitewashed, and Black history is trying to be taken out of school systems across the country, the university is asking to destroy a part of its own history,” said Frank Houston, president of the Historic Waverly Neighborhood Association.

The neighborhood association has written to the university about the worsening condition of the house, he said, adding the university has “deliberately” let the house deteriorate.

Now, Allen is taking the issue to court. In mid-March, the institution filed a formal appeal of the DDRC’s decision in a Richland County court and a request for pre-litigation mediation, saying city officials abused their discretion and that the decision was “arbitrary and capricious” and not based in law.

It’s unclear what Allen University’s plans are for the property or where the mediation efforts stand. The State has reached out to an Allen University spokesperson several times for more information. Those requests have not been returned.

City documents note that Allen University has not provided site plans for what would occupy the area post-demolition.

An unkept promise

This is not the first time the Robert Mance house has made headlines.

In 2008, Allen University decided to move the Mance House two blocks away onto a new foundation in the same neighborhood to make room for an $18 million dorm expansion project. The university promised to restore the home so that it would again be livable.

“The Mance House has been an important part of Allen’s history, and we are proud we have been able to save it,” then-Allen University president Charles Young said at the time.

The house had been used for storage and office space for more than a decade before the move, but the university planned for it to again become a home for the university’s leader once it was restored, according to news reports from that time.

Making it habitable again was also a stipulation for receiving a financial guarantee for the dorm project and the relocation effort from the federal Department of Education.

But the improvements never came. Instead, the house deteriorated. Windows were broken, wood rotted, and dozens of code violations stacked up.

John Sherrer, director of preservation at Historic Columbia, said his organization strongly opposes the demolition of the property. He also said the university should honor the spirit of the 2008 agreement with the U.S. Department of Education in which it planned to restore the home.

“It’s not just a residence, it’s not just someone’s private home. It assumes a greater significance than that,” he said, noting its ties to Allen University and the broader Waverly area.

There’s a possibility that the house could be moved again, both Sherrer and city preservation staff have said. Preservation staff in a report to the DDRC also noted Allen University has not provided an alternative site for that option.

“It’s really a matter of death by a thousand cuts,” Sherrer said when asked what kind of hole the building’s demolition would create if it were to be approved.

“You have other buildings in that neighborhood that have been lost, for a variety of reasons. … Ultimately, if you have your historic fabric chipped away at, over time you’re going to be left with something that in no way, shape or form resembles what it once did as a collective,” Sherrer said.