From altitude camp to taper, base miles to Basque départ: How riders train for the Tour de France

This article originally appeared on Velo News

This is the first in a two-part series investigating the cornerstone components of a rider’s journey toward the Tour de France.

This opening installment explores the nine-month training pathway from early winter altitude camps all the way through to the day of the grand depart.

Check back soon for part two, which will look at some of the accessory elements, from gym floors to running shoes, psychologists to nutritionists.

— —

The Tour de France is no ordinary bike race.

Riders dream about it, Netflix makes shows about it, and the winner’s maillot jaune is an icon.

And just like the Tour de France is a ride like no other, training for the grande boucle isn't the same as it is for marquee races like Paris-Roubaix, the Olympic Games, or the world championships.

From the intricacies of altitude camps to the problem of hitting a three-week peak, being competitive for the biggest race on the calendar requires a grand tour masterplan as massive as the race itself.

Experts from every corner of sport science combine to create a full gestation of training plans and racing schedules designed to deliver the next Tadej Pogacar or Jonas Vingegaard.

"Jonas knew his Tour de France training schedule nine months ago," Jumbo-Visma head of performance Mathieu Heijboer recently told Velo. "Not the exact sessions, but he knew almost exactly would he'd be racing, resting, training to peak. In some cases he even had an idea what he'd be eating."

Also read:

Winning the yellow jersey is a feat that defines riders' careers and elevates teams to a different echelon of the sport. It’s a high-stakes, big-money game that consumes teams’ resources all through the year.

"Planning for the Tour is a massive task for us," Heijboer said. "It involves many, many inputs, and takes weeks to bring together."

Here are some of the most fundamental - and finicky - elements of any Tour de France preparation plan:

The altitude camp arms-race

One of the most labor and capital-intensive elements of any team’s assault on the maillot jaune comes in the planning and execution of a series of altitude camps that bring a racer through winter base miles to pre-Tour perfection

Once seen as a nice-to-have, these 2,000-meter high yellow jersey academies have become a no-question cornerstone for any team looking to top a grand tour.

“Living high and training low” helps a rider boost blood cell count and max out the oxygen-carrying capacity they need to crush TTs and win summit finishes.

"We've been going to altitude a very long time, and I think we're close to finding a winning formula every time. And we've seen it works for Jonas," Heijboer said.

"To be able to get to perform at the highest level in the races we want, we can come very close with altitude training.”

Teams block-book empty ski lodges in the Sierra Nevada and the Alps, or hotels like Teide's Parador, through the winter and spring.

Now that a half-dozen teams might want to be at the top of the same mountain at any one time in the season, getting early access to high-altitude hotels is a small but overlooked element of any grand tour push.

The race for rooms at thin air shows how training at altitude is becoming more important with every passing season.

Get altitude training right and riders could boost threshold power by as much as five percent. Get it wrong, they might be burned out and used up before they even see the pre-Tour presentation ceremony.

And now that every Tour de France team is riding at thin air, getting it wrong means getting left behind. And that’s why the returning Pogacar and his UAE Emirates team are forgoing a tune-up race block altogether this month in favor of sustained pedaling high in the sky.

"We know that altitude works, that's why we put more and more focus there. But you have to do it right to make it really work," Quick-Step coach Vasilis Anastopoulos said. "We're learning more and more how to do it."

Just like any training program, an altitude framework requires a slow steady accumulation of gain.

A season uninterrupted by injury would typically see a rider head to Tenerife, the Sierra Nevada, and French Alps three or even four times before the Tour de France.

"You need repeat altitude camps for the ideal effect. A camp earlier in the season can act as a primer and make the adaptation in the second camp more effective," UAE Emirates performance director Jeroen Swart told Velo. "But that has to be countered with the fatigue that can happen from being at altitude for too long."

Training not racing, and baking in the big base

Only a decade ago, heavyweight races like Paris-Nice and the Criterium du Dauphine were considered essential to any riders’ path to the Tour de France.

GC contenders would layer race-days into a schedule considered the ultimate training for July’s biggest prize.

Fast forward to the 2020s, and stage racing is considered just a high-intensity finisher.

“The only thing you cannot mimic at altitude is the nervousness in the peloton and the accelerations, etc," Jumbo-Visma trainer Heijboer said. “That’s almost becoming the main reason we send riders to many of the races. Before, like when I was a pro, those races would be the training.”

Weeklong races offer big saddle time, a dose of intensity, and for many, the potential for palmares-topping victories. But it’s the back-to-back weeks spent tippy-tapping at altitude where riders bake the big endurance base they need to be competitive for a three-week race.

And in the time-strapped case of Pogacar in his fast-track back from injury, training can deliver all the lactic pain of the hardest days in the peloton.

"You can always do some good training behind a moto and stuff like this to simulate a race," Pogacar said last week. "You can adapt training so it's similar to races, so I'm not so worried this year."

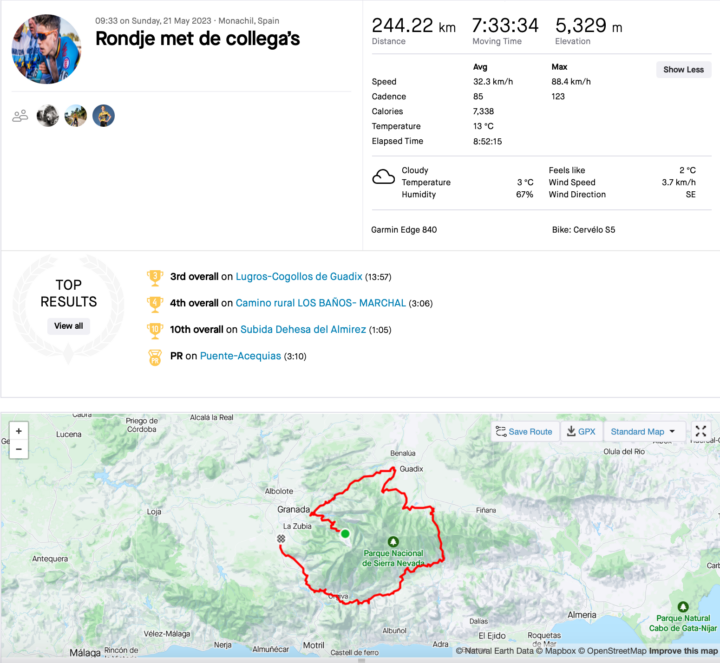

Scrolling any Tour-bound rider's Strava account reveals just how much time is invested into building out the low-intensity foundations that will see them through 80+ hours of grand tour racing.

Wout van Aert's feed from the past month shows repeat seven-hour rides out of the Sierra Nevada as he stacks up training weeks of up to 30 hours.

Van Aert’s Tour de France rivals like Matteo Jorgenson, Romain Bardet, and Fred Wright similarly share training schedules where 25 hours and 600km are a mainstay.

Riders like Vingegaard, Van Aert, and Jorgenson are making rare trips away from “second homes” in the Sierra Nevada and Canary Islands this month to race through northern Europe.

But most of the WorldTour will be back perched on top of mountains throughout Europe before the ski lodges and boutique hotels know it.

Vingegaard and his Jumbo-Visma teammates will spend the final days before the grand depart atop Tignes in the French Alps. Pogacar and his UAE crew will be a few valleys away in Sestriere.

“Training at altitude tends to boost hemoglobin around two or two and a half weeks. So it means that we do have to do a final ‘top-up’ camp of volume and intensity in the weeks prior to the Tour,” UAE Emirates director Swart said. “We work the racing schedule around that concept.”

Taper? What taper?

As Swart alluded to above, a Tour de France rider's training volume doesn't drop, even the week before rollout.

The concept of the “taper” that is so fundamental to one-day events is not part of the Tour de France’s three-week lingo.

"We never drop out the volume sessions, even near the Tour they stay important,” Swart continued. “Think about it. Those last sessions before the Tour, they're still a month from the third week of the race, and that’s typically where the most important stages are.

"You need to keep volume high the whole way, so the base is there for the final stages of racing.”

Marathoners or riders aiming at Olympic or world championship medals typically progress through a seven-to-10-day taper in advance of their A-race. Volume is decreased but intensity maintained, meaning athletes toe the startline fresh and at their peak.

There’s no such luxury for the 176 elite racers set to start the Tour de France next month.

Only faster-twitch sprinters and puncheurs, or those aiming at the first yellow jersey, might drop things down a token few days before the July 1 depart.

"In an endurance training program, volume is something you will never take out. We make sure they're recovered and have the energy reserves, but in some stages, the low intensity in the peloton means there can be a slight 'detraining.' Limiting a taper means you maintain the training adaptations," UAE's Swart said.

The three-week peak

The three-week timeframe of a grand tour doesn't only shift the athletic staple of a “taper.” It also completely reconfigures how trainers plan their athletes' peak.

Grand tours of old would typically start steady with a first week of snoozer sprint stages. GC contenders could roll out a few percent from their peak and easy-pedal toward form while they hid in the peloton.

Chris Froome followed a similar framework in the 2018 Giro d’Italia. He started the corsa rosa at a simmer and raced himself toward a roaring boil in time for his infamous third-week Finestre raid.

But it’s not always that simple. Many grand tour organizers now pepper GC-centric days all through their parcours, and the 2023 Tour de France is no exception.

A hard hilly start in Spain's Basque Country and Pyrenean mountain double soon afterward means riders like Vingegaard and Pogacar could be butting heads, early.

"This year's course makes planning the training and peak more complicated," Jumbo-Visma staffer Heijboer said. "They need you need to be at a very high level from the beginning, all through to the end.

“Holding top, top form for that long is dependent on your basic endurance level. And that’s why Jonas has such a long training period. A bigger base means he can hold a peak level for longer."

‘Training is not an exact science. There’s a lot of nuance’

Sport science is becoming increasingly sophisticated every season. Formula 1-esque advances in training, nutrition, and recovery make fitness and fatigue easier to forecast.

But even now in 2023, staffers know they can't get it 100 percent right.

“Going into this Tour, everybody needs to arrive in close to their peak form. So it's an important thing to balance their shape in the weeks beforehand,” Swart said.

"But there’s only so much we can do based on our own knowledge and experience of the rider. Training athletes is not an exact science. There’s a lot of nuance. There are often unpredictable factors that you can’t measure."

And that's why grand tour racing remains so spectacular. Bonks, blowouts, ambushes, and burnout can still shape the outcome just as much as the nine-month masterplans that take riders to the start line.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.