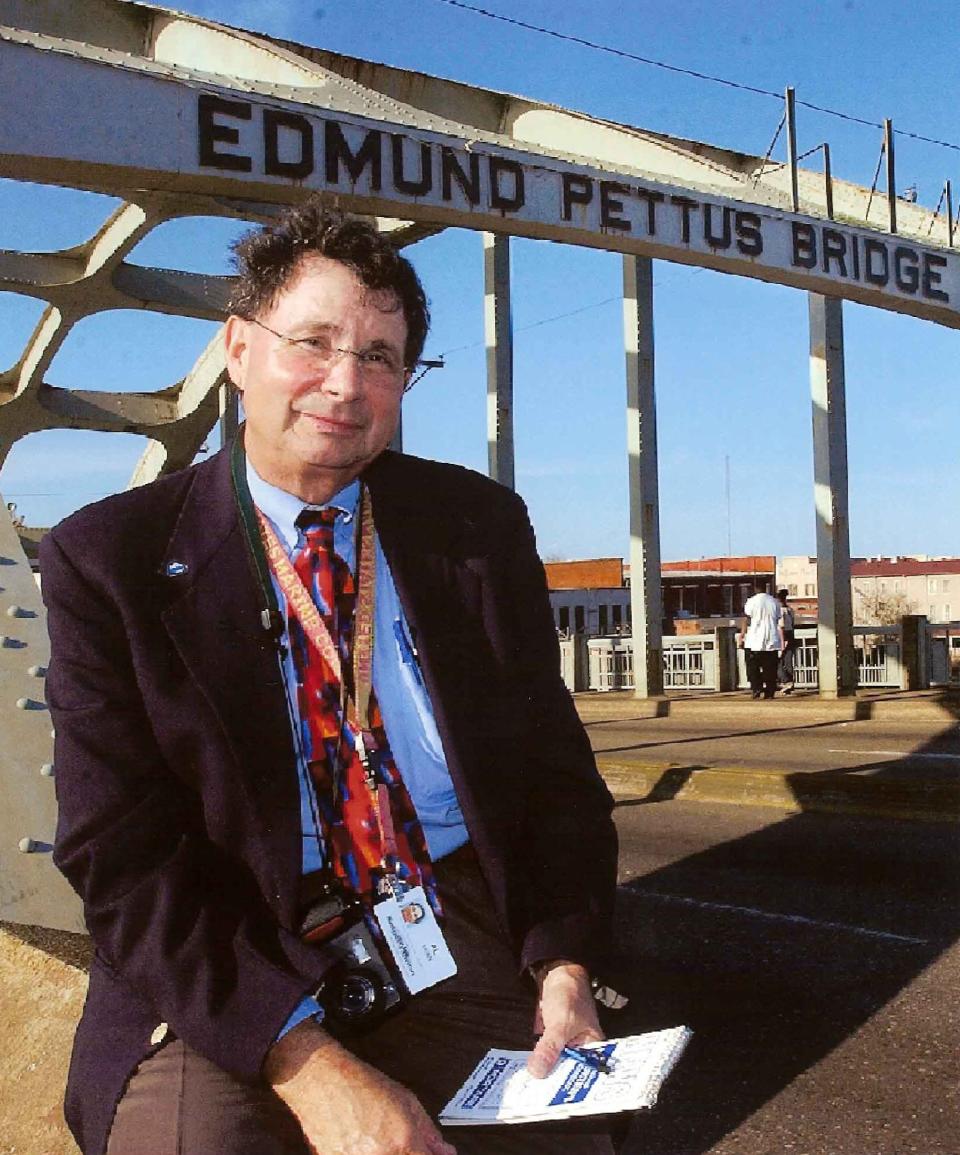

Alvin Benn, longtime Montgomery Advertiser reporter and columnist, dies at 83

Alvin Benn, who traveled all over the South in a 54-year career in journalism and witnessed several historic events in Alabama history, died on Wednesday, Oct. 11, at age 83.

"It is with great sadness that I have to report the passing of my father, Alvin Benn," wrote Benn's son, Eric, in an online message to family and friends. "He was a man of great loves. He loved his family and friends, his religion, the United States Marine Corp, and most of all his job. He dedicated his entire adult life to reporting the news, good and bad. From covering the civil rights in the 60’s, to being nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, to interviewing presidents, to covering the day to day life in the south, to writing a book, etc., he loved nothing more than the State of Alabama and especially his hometown, Selma."

From his start at United Press International on August 4, 1964, to his final byline in the Montgomery Advertiser on July 8, 2018, Benn had a wide-ranging career. On what was supposed to be his orientation day with UPI, editors sent Benn to assist the wire service’s coverage of the discoveries of the bodies of Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner, three civil rights activists murdered in Mississippi the prior month. Later, Benn covered three major civil rights trials in the course of a single year, and secured a small footnote in the history of The Beatles.

"I never tire of hearing the ambulance roaring by and the police car chasing fire trucks, and seeing my name in the byline," Benn said in a 2014 video reflecting on 50 years in journalism.

Tuscaloosa News editor Ken Roberts said it was a privilege to work with Benn for 13 years at the Montgomery Advertiser.

"In my 35-year career, I've worked with a few reporters who stood out for their dedication and their relentless pursuit of great stories. They all take a back seat to Alvin Benn," Roberts said.

Benn considered himself the "Columbo" of reporters, a reference to the TV detective character played by Peter Falk — and could do a pretty good impression: "Ahhh, one more question."

He interviewed Martin Luther King Jr., Hosea Williams and George Wallace. He asked Hank Aaron what it was like to bat against Benn’s childhood hero, Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Robin Roberts. In a Birmingham hotel room, George Lincoln Rockwell, the founder of the American Nazi Party, played Benn a racist song by a group called “The Three Bigots” while he swallowed a half a bottle of a drug intended for babies during teething.

“We all hope to climb that ladder of success to the top one day,” Benn would joke in his 2006 memoir, “Reporter.” “In my case, I started at the top with UPI and it’s been a slow, steady downhill slide ever since.”

What really set Alvin apart was that he brought the same level of dedication to his family life.

"He loved his wife Sharon and his kids every bit as much as he did breaking a big story," Roberts said. "And he was able to balance writing three or four stories a day with being a devoted father and husband."

Brad Harper, the Advertiser's executive editor, said it's hard to overstate the impact Benn’s work had on generations of Alabamians, from his colleagues in journalism to the everyday people whose stories he told. Yet, he was so much more than his words.

"Every Saturday, Alvin and his beloved wife Sharon would bake a cake and bring it into the Advertiser for those of us who were working the weekend shift," Harper said. "The first time I saw it happen, I asked if it was someone’s birthday. But it continued, Saturday after Saturday, for years. It was just who they were."

Many weekends Roberts arrived at the Advertiser to find Alvin writing two stories at the same time while chatting with Sharon about where they would eat dinner. Benn would file his stories and they would be off in their Volkswagen Bug.

"When they left, I would say to myself: There goes the Amazing Alvin Benn. And that's what he was: amazing," Roberts said.

Sharon Benn passed in 2020. The Benns raised two children, daughter Danielle Benn (Curtis) Waters and son Eric Benn, and were grandparents.

"Some knew him by Al, Alvie, Big Al, Mr. Benn, but I knew him as dad," Eric Benn wrote.

Waters offered thanks to her brother and sister-in-law for being loving caregivers to their dad.

"Daddy led an exciting life and now he is returning to Selma, Alabama to be with Sharon Benn at last," Waters wrote.

From the Marines to the news columns

Benn was born on April 25, 1940 in what he called “the poorest section” of Lancaster, Penn. His family were Orthodox Jews; Benn described his mother as “a saint, or as close to one as a Jewish woman could get” and his father as “somewhat of a sinner – a gambler and a man of few social graces.” In high school, Benn wrote that he “struggled” through classes, though he called enrollment in a typing class “the best decision I ever made in high school.”

After graduation in 1958, Benn enlisted in the U.S. Marines, where he served six years. During training on Parris Island, Benn, who was Jewish, attended a Protestant service on a Sunday. The following week, his drill instructor, saying “we have a Jew in the platoon,” screamed “Don’t you know Jews don’t go to Christian services? Get over there with the rest of the freaks.”

In the Marine Corps, Benn began his career covering basketball games for the Marine base in Cherry Point, North Carolina. He later enlisted in the Navy School of Journalism before he was stationed in Okinawa, Japan.

Shortly before his discharge, UPI hired Benn at $90 a week – less than what he made in the Marine Corps. The UPI executive who hired Benn asked him where he wanted to go. “Where the action is,” Benn replied. “OK, you’ll be going to the South,” came the answer.

In his first two years as a reporter, Benn covered several major news stories. UPI sent him to Hayneville to report on the trial of the men charged with killing Viola Liuzzo shortly after the Selma-to-Montgomery march concluded in 1965.

“It was obvious from the start that Liuzzo was all but forgotten,” Benn wrote. “She represented people and a culture loathed by many in the South. On trial was a way of life – nothing more, nothing less.”

Benn also interviewed Willie Brewster, a 38-year-old married father of 2, after 3 white supremacists shot him outside Anniston in 1965. Brewster died three days later; his wife was pregnant with their third child. Benn covered the trial, which led to a conviction of one of men charged with Brewster’s murder. It was the first time during the civil rights movement that an all-white Alabama jury convicted a white man of the murder of a black man.

Following Brewster’s trial, Benn went back to Hayneville to write about the trial of Tom Coleman, charged with the murder of Episcopalian seminarian Jonathan Daniels in August, 1965. An all-white jury acquitted Coleman.

“No one was surprised, including me,” Benn wrote. “It was the third trial of its kind that year at the little courthouse.”

Benn also covered the space race and the deaths of American servicemen in Vietnam. In August, 1966, Benn was driving to the UPI office in Birmingham when he heard two local disc jockeys tell listeners to “send in all your Beatles records for our bonfire,” following published comments from John Lennon that the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.” Benn called the DJs for comment, then wrote a story for UPI on the controversy. It was the first article on a controversy that sparked a national frenzy and led to Lennon addressing the remarks later in the month.

After his time at UPI, Benn worked at the Decatur Daily as an editor and reporter, where he wrote an in-depth series on poverty among the local Black community and launched a “Spirit of America” festival, which he said was intended to counter anti-war protests about Vietnam. Benn later worked as an editor for the Natchez Democrat in Natchez, Mississippi, the Alexander City Outlook and the Walker County Messenger in Lafayette, Georgia.

In 1979, Benn moved to Selma, which would be his home for the rest of his life. After a brief run at the Selma Times-Journal, he joined the Montgomery Advertiser in 1980 as the Selma bureau chief. Benn covered local news, crime and politics, and in later years wrote a column called “Alvin Benn’s Alabama,” which he also recorded for blind and visually impaired listeners.

By the time of his retirement from daily journalism in 2003, Benn estimated he had written 20,000 stories and driven nearly 1 million miles for the Advertiser. Shortly after he stepped away from regular reporting duties, “To Kill A Mockingbird” author Harper Lee saw him at an event in Selma and said “You retired, you bastard.”

But Benn continued to contribute to the Advertiser, filing a regular column and taking Saturday morning shifts to allow younger reporters on staff to have time to themselves on weekends. His final story in the Advertiser ran just a month short of what would have been his 54th anniversary in journalism.

In his final column as a daily reporter, printed on Monday, May 5, 2003, Benn said he didn’t expect to fully retire, but that he had “to learn how to relax.”

“People say I’m such a Type ‘A’ guy that I’ll start going crazy on Tuesday,” he wrote. “No way. That won’t happen until Wednesday. I’ll be mowing the lawn on Tuesday.”

Former Montgomery Advertiser reporter Brian Lyman is the editor of the Alabama Reflector. Contact Montgomery Advertiser reporter Shannon Heupel at sheupel@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Montgomery Advertiser: Alvin Benn, longtime Advertiser reporter and columnist, dies at 83