'Always living with a smile on his face,' but SHS coach is up against the fight of his life

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

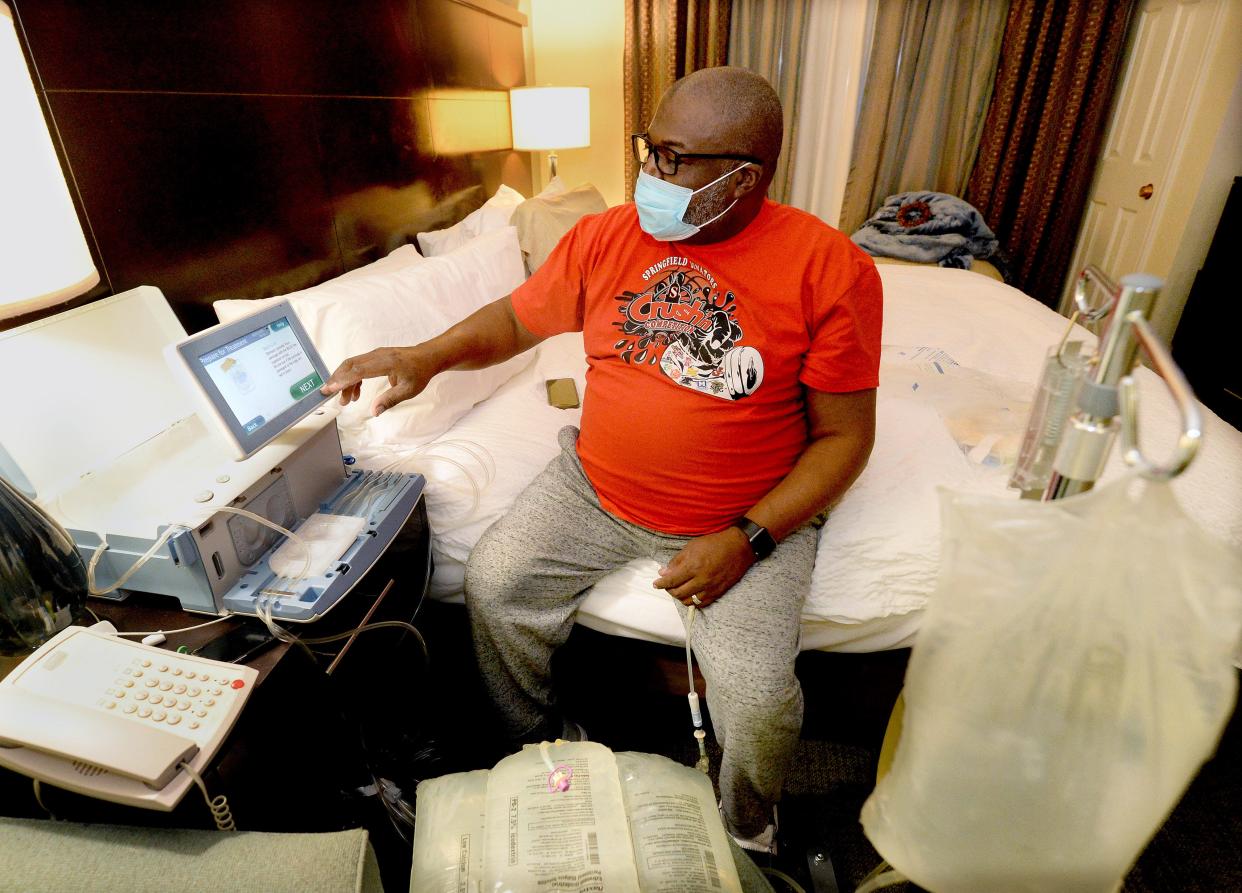

Ali Upshaw sits on the edge of his bed surrounded by large bags of clear solution with tubes coming out of them. On his nightstand, a machine softly hums when a programmed voice isn't giving him directions.

By now, he has the peritoneal, or home dialysis system down pat.

"I've done this hundreds of times," Upshaw said assuredly.

More: Rev. King spoke at the Illinois State Armory in 1965, his visit will be commemorated

For just over a year now, Upshaw, an assistant boys basketball coach at Springfield High School which begins City Tournament play against Lanphier at 8 p.m. Thursday, has been in renal failure, meaning his kidneys are shut down.

Upshaw sets up the machine for a nine-hour overnight treatment. The machine makes sure, among other things, that the lines work properly and the solution is properly warmed.

Before he goes to sleep, Upshaw hooks a line into a catheter in his stomach. While he sleeps, the solution takes bad toxins out of his body.

Three medical centers in the Midwest are looking for a kidney match for Upshaw.

Meanwhile, his wife, Tonya, is praying for a miracle.

"We're trusting and believing in God," she said, "that (God) is going to make a way and provide for this to happen, for this miracle to happen sooner than we think."

Faith and resilience have sustained the Upshaws.

Just after Thanksgiving, the couple and two of their children, Tatyana Gardner and Amir Upshaw, were displaced by a house fire, so they've been living in an extended-stay hotel since. They hope to be back in their home sometime in the spring.

A dental technician and supervisor at Ottawa Dental Clinic (formerly Oratech) in Springfield, Upshaw, a Southeast graduate, is better known as a basketball coach. He met SHS head coach Marques Warfield when Warfield was coaching his son. The two hit it off and when Warfield was named head coach over the summer, he brought Upshaw aboard.

Upshaw said he won't deterred by the setbacks.

"I just live life," Upshaw said. "I'm not going to let this stuff beat me up. Do I have some bad days? Yeah, it comes with the territory. I do things to keep the disease off my mind. I know it's there because at some point in time during the day I have to treat it.

"Do I think there's a kidney out there for me? Yes. And it's coming."

A transplant candidate

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 35.5 million adults in the U.S., more than one in seven, have chronic kidney disease (CKD). As many as nine in 10 adults who have CKD aren't aware they have it.

The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), a private, nonprofit agency that works under contract with the federal government, reported that 92,000 people in 2023 were on waiting lists for a kidney.

More: Marques Warfield replaces Joby Crum as Springfield boys basketball coach

Some 27,500 Black patients, like Upshaw, are on the kidney transplant list, representing 30% of the candidates nationwide, despite Blacks making up 13% of the population, according to UNOS.

A complicating factor for Upshaw is that he is an O-positive blood type. While it is the most common blood type − 37% of the population have it − it is also in high demand because it is the most frequently occurring.

The common causes of kidney disease in the U.S. are diabetes and hypertension, or high blood pressure, said Dr. Max Nutt, a board-certified nephrologist at the SIU School of Medicine and a Springfield native.

In an ideal world, he said, everyone would know whether or not they had high blood pressure or elevated blood sugars.

"The reality is that's an area of improvement," Nutt said.

The fact that a lot of people are walking around with CKD and aren't aware of it doesn't surprise Nutt because it doesn't present symptoms.

The 54-year-old Upshaw, an Army veteran who served in Operation Desert Storm and in Somalia as a transportation specialist, was diagnosed with CKD in 2020. At that point, his condition was being monitored by doctors every six months, but Upshaw wasn't on any medication for it.

During a trip to California in August 2022, Upshaw experienced shortness of breath. Doctors found his lungs were filled with fluid, and, through blood work, that his kidneys were failing.

Because of the precipitous drop, down to 12% kidney function, Upshaw had to go on in-clinic dialysis in September 2022. He took a three-week course to learn how to give himself the home dialysis, though he is still required to visit the Fresenius Kidney Care Clinic here twice a month.

Because Upshaw's kidneys aren't working, the dialysis "is my kidney, basically," he said.

When Upshaw went on dialysis, he became a candidate for a kidney transplant. He had to go to three different medical centers in the region − Barnes-Jewish in St. Louis, Indiana University Hospital in Bloomington, Indiana and Northwestern Medicine in Chicago − to get checked out physically.

Any one of the three could call him with a match. An average wait is between three and five years, according to the National Kidney Foundation.

"They turn your body inside out to see if they can find anything else wrong with you because they want to make sure that your body is able to handle the surgery when your time comes," Upshaw said.

And when that time comes?

"We're getting in the car," Upshaw said, "and driving."

'He's going to get through it'

Springfield High's Paul Hartman III is 6-foot-6 and weighs 210 pounds.

Hartman was good enough to attract Division I football recruiters over the past few years and in the fall, will suit up for Coastal Carolina University, a member of the Sun Belt Conference.

But Hartman, whose father, Paul, starred at Lutheran High School and Greenville University, started playing competitive travel basketball in the fourth grade when he met Warfield and Upshaw.

From school construction to street openings, what to look forward to in 2024

"'Ques' is really an intense guy," Hartman said of Warfield, during a break in the Senators' practice at Dewey Gym. "He's always up in your face, making sure you're always going 100%, pushing yourself. Coach Ali was kind of like the balancing force to that. He always had the jokes."

Warfield calls Upshaw "the yin to my yang, so to speak.

"We've been able to bond," Warfield added. "He's a lot more reserved. I'm a little fiery, so to speak. Sometimes my passion can be mistaken for what it's not."

Upshaw, Warfield said, handles the substitution patterns during SHS games. The two know each other so well, Warfield said, that a player will be headed to the scorer's table without the head coach having to say anything.

Players who didn't know Upshaw's condition found out about it during a post-game discussion earlier in the season when coaches were talking about the obstacles in life they were going through, Warfield said.

"That made them respect him more," Warfield said after the players heard Upshaw. "There are some times he can't come to games or stay the full duration of practice because of his (medical) situation. When he speaks or he pulls kids over to the side, they are locked in. There's that level of respect because they know this individual is here despite it all."

Hartman, the SHS player, said his family grew close to Upshaw during the years of traveling throughout the Midwest playing AAU basketball. They were happy to be reunited with him at SHS.

"He's always living with a smile on his face," Hartman said. "You wouldn't even know what's going on behind the scenes. That shows how strong of a person he is and how caring of a person he is.

"The fact that he has to go through that on top of coaching and traveling with us and all of that, it does show a lot of his character."

Warfield marvels that Upshaw keeps going, despite the setbacks.

"It's one of those situations where your perspective is everything," Warfield said. "Your faith is everything. Your family support system is everything. All of those are going to be major factors in helping him get through this because he's going to get through it.

"They're really some good people. They've had a tough few years. One thing I will say is they keep going. They find a way."

'A new perspective on life'

Upshaw admitted one of the biggest obstacles may have been coming to grips with his illness.

Once he maneuvered that, Upshaw insisted he was going to keep doing the things he enjoyed doing, like coaching basketball. He still runs the AAU program out of The Gym in Springfield, in addition to assisting at SHS.

"I enjoy kids," Upshaw said. "I like watching them grow and I enjoy coaching them. That's kind of my happy spot, my happy place."

Dawn Sterling set to join WICS-TV as news anchor after nearly 20 years at WAND

Upshaw also has acknowledged his limitations. To get the nine-hour dialysis treatment in, Upshaw has to start it nightly at 8:30 p.m. to get up and be at work by 6:30 a.m.

He has a little more leeway on weekends when he doesn't have to work.

"Our whole life, our whole dynamic has changed," said Tonya Upshaw, who works for the governor's office of management and budget. "With our trust and our belief in God and our faith, it makes it a little bit easier. When I look at Ali and I see just how mentally and emotionally he has prepared himself for this journey, you can't help but to grasp onto that.

"The same way with our children. They have adapted to this lifestyle. We can still have a wonderful, productive life. We just have to do it a little differently."

Tonya said her husband wants to be able to watch his grandchildren grow up − the couple's first grandchild, Teaghan, is four months old. He also wants to give his only daughter away on her wedding day.

"Those are the kinds of things you think about," she said.

The illness also reinforced the importance of having a support system.

After getting on the transplant list, both were assigned social workers. Tonya had to go through a psychological evaluation.

Nurses assigned to Upshaw at each of the transplant units include the couple in any discussions.

If Upshaw received a transplant, he would have to be watched 24 hours a day for three to four months, Tonya said. There would be twice weekly doctor's visits to one of the out-of-town medical centers as well.

The best bet is for Upshaw, or any recipient, Nutt said, to get a living donor kidney transplant. On average, a living donor kidney lasts longer and has better function than a deceased donor kidney, he added.

About one-third of all kidney transplants performed in the U.S. are living-donor kidney transplants, according to information from the Mayo Clinic. The other two-thirds involve a kidney from a deceased donor.

Upshaw said doctors haven't given him a life expectancy timeline. Upshaw said they have told him he is relatively young for his condition, a positive, and he doesn't have any other health concerns.

Upshaw's treatment has opened his eyes to less optimistic situations.

"Even though I'm sick and need a kidney, I really feel bad for other people who are sick because I don't know if they're handling their situation upbeat like I am mine," Upshaw said. "You just look at these people, some have underlying health conditions, and you know from what you're going through, that they're not even going to be able to get on a list. That hurts me.

"So as long as I know I have a chance, I'm going to stay upbeat. We're going to keep doing what we do."

Contact Steven Spearie: 217-622-1788; sspearie@sj-r.com; X, twitter.com/@StevenSpearie.

This article originally appeared on State Journal-Register: Springfield High assistant basketball coach Upshaw needs a new kidney