'As always, Steve': Corresponding with Sondheim, note by note

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

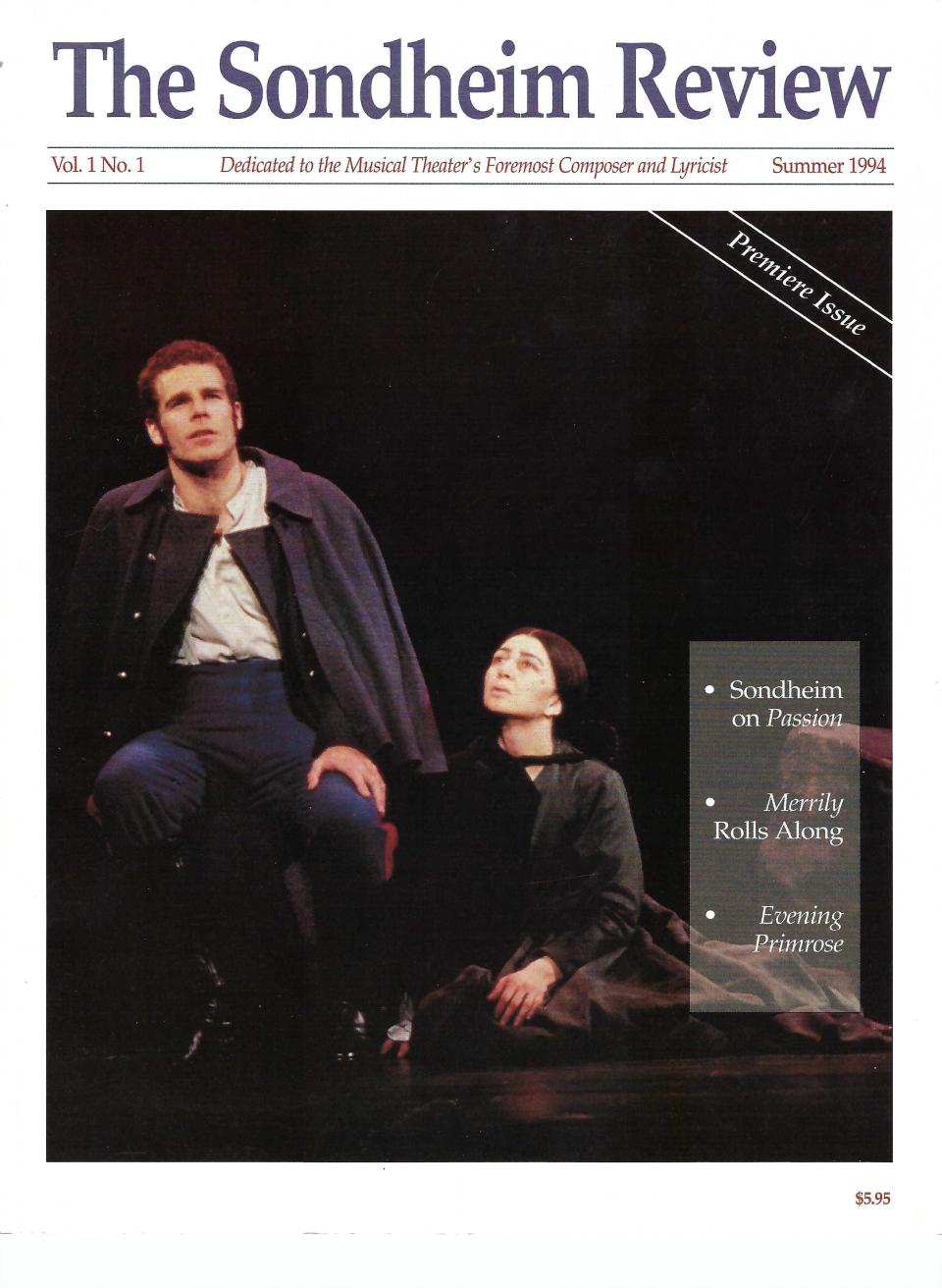

In 1994, when I decided to publish a magazine devoted to the works of the legendary composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim, I feared there would be a major obstacle: I was in Milwaukee and he was in New York.

No problem. Sondheim graciously gave me the phone numbers for his homes in New York and Connecticut and even gave me his fax numbers.

But since his death on Nov. 26 I have been going over the notes he sent me in the 10 years I was editor of The Sondheim Review. While we had long talks on the phone and I received multiple-page faxes, I treasure these typewritten little cards, usually signed “As always, Steve.”

Our first issue in the summer of 1994 included a letter from Sondheim: “I’m flattered and embarrassed and delighted at your interest. I can only hope there will be enough news to justify publication. Thanks for the support. Happily, Stephen Sondheim.”

We promoted the issue with “Sondheim Review” sweatshirts and I sent one to Sondheim. He thanked me in reply and said he loved sweatshirts but wearing it in New York might “seem a bit like self-advertising.” He would, however, wear it in the country.

After the next issue he wrote: “I enjoyed #2 very much, and even learned some things I didn’t know.”

He was sometimes prickly, starting off a note with: “Dept. of Corrections and Emendations.” But he also wrote things like “The new issue looks very good indeed” or, my favorite, “The magazine looks classy and the articles are literate, accurate (for the most part) and not too hagiographic — congratulations.”

Another letter began: “The new issue looks swell, and I particularly enjoyed (name withheld) exegesis on ‘Saturday Night’ (although you might tell him that the opening figure in ‘All for You’ is a rising sixth, not a fifth).”

I wondered how many readers knew the difference between a rising fifth and a rising sixth.

He obviously read every word of every issue. Just one example:

“In reference to the Fall issue, David Shire did more than ‘new orchestrations’ on ‘Tick Tock’ — he wrote the music. And anent the ending of ‘Company’ in Boston, Bobby was not sitting on a park bench but by a pool. And he was not approached by a ‘previously unseen person, a member of the vocal minority,’ but by Teri Ralston, playing (as did everybody else) a character during the course of the show. And despite Hal’s (Prince’s) recollection, the reason the show was cut was that it was a half hour too long.”

We once asked him which of his works met his original vision best. His partial answer:

“Certainly ‘Passion’ was closer to what I’d imagined, though in fact I didn’t have any particular vision of it. I’m not primarily a visual thinker. In the case of ‘Sweeney Todd,’ it was exactly the reverse. Hal’s idea was entirely opposite to mine. I had conceived of it as a small chamber melodrama and he latched on to it as a large-scale epic melodrama, almost Dickensian in scope, resonating from the industrial revolution and the social setup that resulted in England in the first half of the 19th century. It was a much more political view than I ever had.”

He could become excited about productions of his shows: “I went to Barcelona to see the Catalan production of ‘Sweeney Todd’ that gave rise to the recording mentioned on p. 29, and it was one of the most thrilling experiences I’ve ever had in the musical theater: full of ferocious energy, over-the-top performances (even the set made the actors look larger than life) and brilliantly detailed staging (they had three months to rehearse, as opposed to the American five weeks’ worth and the British eight).”

In February 1998, he had news: “We hope to have a reading of ‘Wise Guys’ in May and a production in Washington next February. At the moment we’re working on a few revisions in the first act; the score is still only half done.” (The show, renamed "Bounce," had its first productions in Chicago and Washington in 2003.)

Complaints about reviews, but still encouraging

We went back and forth, via notes, faxes and phone calls, when he objected to reviews by one of our critics. I wrote that I found them “fair, accurate and informative.” He called to complain, but then sent a note: “My apologies for getting so upset over the phone, but, as one of your readers pointed out, (name withheld) gives falsified reports, according to the way she feels.”

After we published stories about his musicals from college, “Phinney’s Rainbow” and “All that Glitters,” and another, “Lady or the Tiger,” which he wrote, at 24, with Mary Rodgers, he was again upset:

“I must say that I object vigorously to your reprinting my juvenilia. Not only is it embarrassing, but I feel you are nibbling me to death. No more, please.”

We didn’t entirely obey.

For all of that, Sondheim was always encouraging. Letter after letter concluded, “Congratulations on another good issue,” “Everything seems kosher,” “Keep up the good work” and “Just a note to say how much I enjoyed the ‘Anyone Can Whistle’ issue. It was a good idea, well executed.” And again: “Congratulations on another good issue — I was particularly impressed and entertained by the article on casting ‘Follies.’ As always, Steve.”

In 2011, I donated my large Sondheim collection of DVDs, CDs, videotapes, audiotapes, books, programs, photos, clippings, etc. — and the notes — to Marquette University. It established the Stephen Sondheim Research Collection and is open to the public.

I don’t need those items to remind me of my extraordinary — if long distance — personal relationship with Stephen Sondheim. But why do I feel that he’s looking over my shoulder as I write this?

Paul Salsini was a reporter, editor and staff development director at The Milwaukee Journal. He can be reached at psalsini@execpc.com.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Corresponding with Stephen Sondheim, note by note