Alzheimer’s disease is on the rise in SLO County — and it’s putting stress on local caregivers

Arroyo Grande resident Bernadette Hiser first realized that something was wrong when she tasted her husband’s pork roast.

Jeff Hiser often barbecued for his family. However, this dish “tasted horrible,” his wife recalled.

“It wasn’t like normal,” Bernadette Hiser said of the pork roast. “I found out he had forgotten how to make the pork roast and so that’s when we went to the doctor.”

In 2015, Jeff Hiser was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, a type of dementia that affects memory and other mental functions. It’s the leading cause of dementia in the United States.

Jeff Hiser is one of nearly 720,000 people living with Alzheimer’s disease in California, which leads the nation in cases of the disease according to a 2023 study by the Alzheimer’s Association.

Projections from the Alzheimer’s Association projections show 840,000 Californians over age 65 will be living with Alzheimer’s disease by 2025.

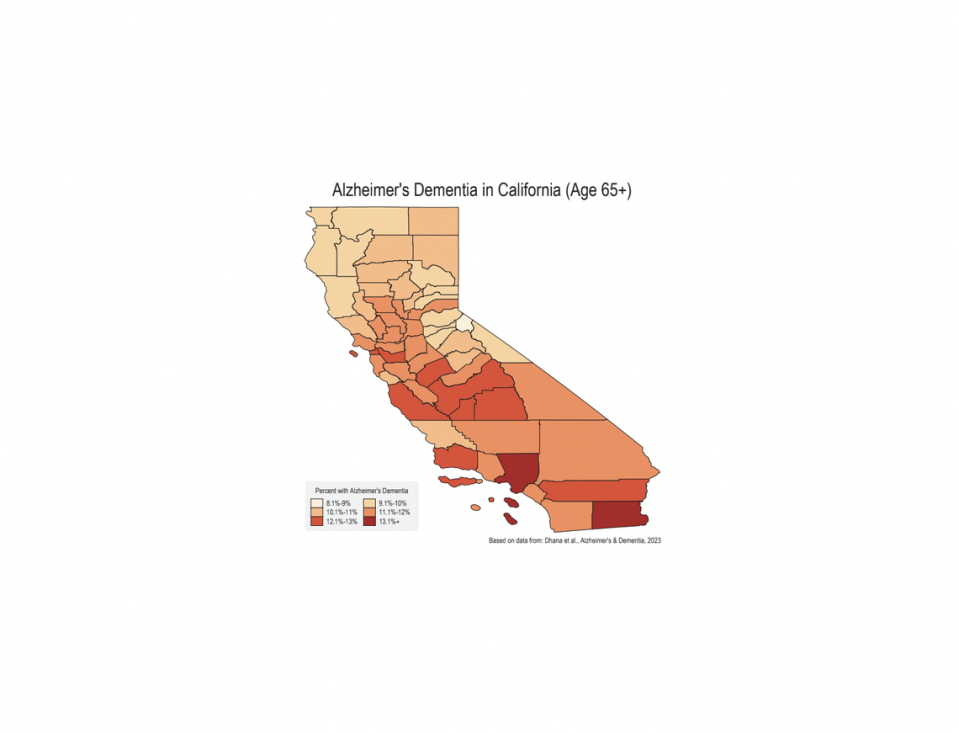

The prevalence of Alzheimer’s is particularly high on the Central Coast.

In San Luis Obispo County, 10.6% of the population 65 and older has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease as of 2023, the data shows. Marin County in the North Bay Area has a similar Alzheimer’s prevalence at 11.1% of residents over 65 and nearby Monterey County with 12.1% among the same population.

The Alzheimer’s Association shows a 281.5% increase in deaths between 2000 and 2019 from the disease.

SLO County families talk about dementia diagnoses

Jeff and Bernadette Hiser have been married for 46 years and have two grown children.

The couple met while Bernadette Hiser was working as a school bus driver for Newport Mesa Unified School District. Jeff Hiser worked on the district’s landscape crew, she said.

They later moved to San Luis Obispo County.

The couple’s lives changed when Jeff Hiser was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease eight years ago, his wife said.

His condition progressed slowly at first, Bernadette Hiser said. Now, her husband struggles to speak and cannot follow conversations.

“With this disease, the plateaus stay a long time, but then the dips come quick,” said Hiser, who has been her husband’s primary caregiver for the past eight years. “You just never know when something’s going to happen, or (if) he’s going to be different.”

“Unfortunately, I don’t think anybody can understand what you’re going through unless you actually live it,” she said.

San Luis Obispo resident Chris Broome can empathize with the Hiser family’s experience with dementia.

While on vacation in 2013, he noticed his wife, software developer and artist Alyce Broome, was unusually forgetful. He recognized the warning signs of dementia, having watched his mother-in-law live with the disease for 14 years.

After a long consultation with a San Luis Obispo physician, Alyce Broome was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia in the spring of 2013. With that disease, cognitive decline is unpredictable, her husband said.

“The patient’s cognition can remain pretty stable for a while, then it can suddenly drop,” Chris Broome explained. “And that drop could be tiny or that drop could be very large.”

By the spring of 2022, Alyce Broome’s dementia had worsened.

The former software programmer now needed her husband’s help to operate anything with buttons, such as the microwave and the television remote. The couple could no longer participate in the intellectual conversations they once enjoyed, Chris Broome said.

“It’s like the converse of watching a child grow up,” Broome said. “When you see it on a day-to-day basis you don’t know anything is happening. But then, if you think back to what it was like several years ago, you’ll notice that the differences can be fairly significant.”

After nearly a decade living with Lewy body dementia, Alyce died on March 6.

“Dementia is a journey with only one destination,” Chris Broome told the Tribune after sharing the news of Alyce’s death.

For caregivers, he added, “Sometimes reaching that destination is a relief.”

Dementia caregivers describe isolation, stress

Broome and Hiser said that caring for a loved one with dementia can feel isolating.

“A lot of our friends have dropped off — they don’t come around,” Hiser said. “You do feel very lonely.”

In social situations, she said, “I don’t have anything happy to say, and not everyone wants to be around a person that has a sad story. And that’s the honest truth.”

Bernadette Hiser said being her husband’s primary caregiver is probably the hardest — but the most rewarding thing — she will ever go through.

“It’s taught me a lot about myself,” she said. “When you’re up against a wall, what are you going to do?”

According to Broome, becoming a caregiver for a spouse living with dementia can change the nature of that relationship — but that doesn’t mean there is an absence of love.

“I think I care for (my life) a lot more,” Broome told The Tribune in 2022. “I think I love her a lot more.”

Lack of resources pushes caregivers out of workforce

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 80% of individuals who have Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia are cared for at home.

In many cases, family members or friends caring for those with dementia have to reduce work hours or quit their jobs entirely in order to care for their loved ones, said Lindsey Leonard, executive director of the Alzheimer’s Association’s Central Coast chapter.

“This is a disease that is a national and global health crisis,” Leonard said.

In 2023, Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia will cost the U.S economy $345 billion, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

That doesn’t include wages for the nearly 11 million Americans that provide unpaid care for individuals with neurodegenerative diseases, the association said.

Hiser left her job as a real estate agent at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic because she was afraid she or her husband might get sick.

“I’d still love to be out there working,” Hiser said. “I’d say you lose yourself on this journey.”

More than 1.3 million people in California provide unpaid care to individuals with Alzheimer’s dementia in 2022. That unpaid care is valued at $44 billion, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

Adult Day Center helps people with memory problems

In San Luis Obispo County, there is just one daytime memory care facility for older adults and people with memory problems — the Adult Day Center, a program run by the Community Action Partnership of San Luis Obispo (CAPSLO).

“The goal of our program is to provide older adults that have memory impairment, dementia or Alzheimer’s disease a safe place to go during the day,” Adult Day Center manager Mara Whitten said, “while also providing respite and support to their family caregivers.”

The Adult Day Center — or as many participants call it, “the club” — first opened in Templeton in 2004, and now operates on the campus of St. James Episcopal Church in Paso Robles.

The homey facility, which has a donation-based payment plan, can care for 25 participants at a time with a ratio of one supervisor to every five participants.

“Socialization is better than any pill they can give someone with dementia,” Whitten said. “That stimulation is so important, otherwise many people that have dementia are isolated and will suffer from depression, lose the abilities they have, spend the day watching TV, and have no connection with friends.”

Whitten said it’s also important to give dementia caregivers a break.

People who care for dementia patients are at risk for developing conditions such as anxiety, depression and an overall poorer quality of life, the CDC says.

In California, about 61% of caregivers for Alzheimer’s patients have chronic health conditions. Also, 18.6% of caregivers in California suffer from depression.

About a quarter of people that provide care to a loved one with Alzheimer’s are also the primary caregiver for at least one child under the age of 18, according to the CDC

Dementia patients cared for at home

Although Bernadette Hiser prefers to care for her husband at home, that comes with its own set of challenges, she said.

Hiser has a chalkboard on the wall where she writes notes to her husband specifying where she is and when she’ll be back, so that she can run errands or walk their dog, she said.

“I can still leave the house, but not all day long,” Hiser said. “I just wouldn’t be comfortable with that.”

Near the end of her illness, Alyce Broome sometimes wandered, her husband said. He installed alarms on the doors and eventually realized that he couldn’t leave her unsupervised in the home.

Although there are paid and volunteer caregivers on the Central Coast who can come to patients’ home and provide assistance, Broome said scheduling was challenging, since sometimes he only needed help for shorter intervals.

The Hisers tried a volunteer program where an outside caregiver came to their home, but Bernadette Hiser didn’t feel like the caregiver shared a strong connection with her husband, she said.

At some point in the future, Hiser acknowledged, her husband might need to stay in a long-term care facility for around-the-clock care. “It’s hard for me to think about,” she said.

Along with the emotional difficulties of someday living apart from her husband, Hiser worries about the costs of placing Jeff in a long-term care facility because insurance wouldn’t cover any of the costs.

“That’s all on me,” she said, noting that care at one facility starts at about $5,000 a month. “That’s kind of daunting.”

Medicare covers the cost for up to 100 days of skilled nursing home care in a single benefit period, but extended and long-term skilled nursing home care are not covered.

Being a primary caregiver comes with the added pressure of being on top of things all the time, Hiser said.

“If something happens to me, what happens to him?” she asked.

That’s where getting involved in local support groups and Alzheimer’s education classes has helped, Hiser said.

Alzheimer’s Association offers classes, support

Hiser participates in a local caregiver support group sponsored by the Alzheimer’s Association’s Central Coast chapter that meets once a month.

“We’re like family,” Hiser said. “The biggest part is that they understand what you’re going through.”

Before the COVID pandemic shut down in-person meet-ups in 2020, Chris and Alyce Broome attended Alzheimer’s Association support groups, where they were able to connect with other couples dealing with with dementia.

“It helps to have someone to share the experiences with you, because you can often learn from other people’s experiences,” Broome said.

While the connection is good, “Sometimes it gets a little depressing to see things going downhill,” he said.

Broome and Hiser recommended the educational classes offered by the organization, which cover topics ranging from how to work with dementia patients to the logistics of finances, living trusts and power of attorney arrangements.

“For people that are just starting this journey, they really need to go to classes and understand,” Hiser said.

As Alzheimer’s disease becomes more common, experts worry there will not be enough caregiving and healthcare resources available to meet demand.

“I think it’s a worry everywhere, not only in our nation, but beyond,” Leonard said. “The more we know, the more we can prepare.”

What are warning signs of memory loss?

Early detection of dementia is important.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, the 10 warning signs of memory loss are:

Memory loss that disrupts daily life;

Challenges in planning or solving problems;

Difficulty completing familiar tasks;

Confusion with time or place;

Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships;

New problem with words in speaking or writing;

Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps;

Decreased or poor judgment;

Withdrawal from social activities and

Changes in mood or personality.

How to get help

The Alzheimer’s Association Central Coast chapter offers many free resources for families dealing with dementia, including classes, support groups, care consultations and a 24/7 hotline. Call 800-272-3900 or visit alz.org/cacentralcoast.

CAPSLO’s Adult Day Center offers socialization opportunities for people with memory impairment at a sliding scale. Care is available 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday to Friday, at St. James Episcopal Church, 1345 Oak St. in Paso Robles. Call 805-239-5679 or visit capslo.org/adult-day-center.

More caregiver resources are available at the Coast Caregiver Resource Center at Cottage Hospital in Santa Barbara. The resource center is one of 11 regional caregiver resource centers in California. Go to cottagehealth.org/services/rehabilitation/caregiver-services.