Amazon lessons for voters, taxpayers, New York and the 237 other places that bid for HQ2

I ran economic development strategy for New York City during part of Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s tenure. And when New York was digging out of the 2007-08 financial crisis, I helped develop his economic growth plan that focused on technology and entrepreneurship.

I’m also a taxpayer and a voter.

In all of these roles, I can see a lot that went wrong in the wake of the messy breakup between Amazon and New York. Everyone wants jobs to come to their city or town. The Amazon saga holds many lessons and raises many questions, starting with this:

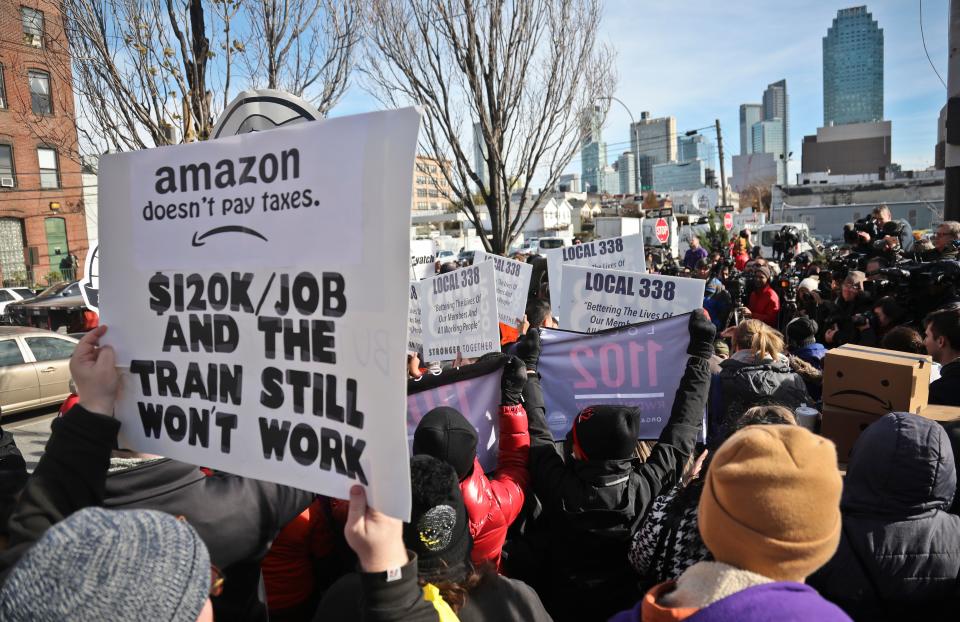

►Why did Amazon deserve a discount? It costs lots of money to run a city, and taxes are how we pay for services like schools, police and fire. Most of Amazon’s competitors and peers (Google, Facebook, Salesforce, Apple) came to New York and expanded without government tax breaks on the scale of what Amazon was offered.

The justification for giving Amazon a special deal was something like: It was a large, prestigious catch and would open part of Queens, a city borough across the East River from Manhattan, as an important new business district. But were the potentially $3 billion in incentives necessary? And what was New York’s plan for handling other companies demanding similar deals going forward?

Read more commentary:

Amazon played us: New York state senator

Losing Amazon HQ2 brands New York as anti-business

New York's Amazon rejection exposes US opportunity gap

Also, the cost of living in Crystal City, Virginia, (the other HQ2 location, now the only one) is about the same as in Queens. But by most accounts, New York's package was much larger per worker than Virginia's. Were the New Yorkers just bad at negotiating, or did they have substantive reasons for their generosity? And did they know what was on offer from other cities?

►What’s happening to those 25,000 jobs? Amazon has said that the 25,000 jobs proposed for New York aren’t going to Crystal City, and that it is not reopening the search for a new location. After a multiyear site search, it seems odd to walk away at the first sign of trouble without announcing a Plan B.

Was Amazon driven away by New York resistance, or did it conclude it no longer needed the space? The history of economic development tax incentives is littered with projects that were structured around a specific company and fell apart when the company’s circumstances changed. A city or state should always plan for that contingency.

►Bait-and-switch is a lousy economic development policy. New York Mayor Bill de Blasio wrote a column complaining about all the things Amazon could have done to avoid this debacle. Some of his points were valid, some less so. But if he wanted Amazon to commit, for example, to “invest in infrastructure and other community needs,” that should have been part of the contract negotiations. Amazon was entitled to know those conditions upfront, not after the deal was announced.

Companies make business decisions based on profitability, not on good press for politicians. If you want a corporation to do something, it should be part of the business deal — not something you insist on afterwards.

►Celebrate the companies that pay full freight. At about the same time Amazon announced HQ2 in New York City, Google announced a New York City expansion involving a several billion dollar real estate purchase. It had enough space for more than 12,000 additional highly paid Google employees. And this was happening without tax subsidies.

Google’s type of growth was what New York should have been celebrating, loudly and proudly. Not the Amazon deal with its billions in tax breaks. To put this in private sector terms, if you’re running an airline, would you want passengers paying full price or passengers getting a very large discount?

Airlines offer discounts, and sometimes so should cities regarding taxes. But cities should never lose sight of which type of taxpayer is more valuable. As with an airline, try to be nicest to the taxpayers paying the full rate.

►New York leaders should "play offense." Former Oath and AOL CEO Tim Armstrong made that excellent suggestion to de Blasio and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, advising them to send Requests for Proposals to the world’s largest tech companies for what would have been the Amazon site. If they thought this was a good deal for New York, why not look for another tech giant to come to the city on similar or even less generous incentive terms?

More significant, why didn’t they do that in the first place? Amazon should have been forced to compete against other companies for a package this size. Competition is how cities can make sure they get the best value for their incentive dollars.

When the Bloomberg administration decided it wanted another top-tier engineering school, it took control. The city sent out Requests for Information, followed by Requests for Proposals, to the world’s best universities. We presented what New York wanted and what the city would provide, and let the participants make proposals to us. The result was the Cornell-Tech campus on Roosevelt Island.

►A toxic political environment is a turnoff. My sense is at least some politicians criticizing the Amazon deal were play-acting. They assumed Amazon would make some meaningless concessions and they could claim them as victory (trust me, President Donald Trump learned his negotiating style in New York City).

It's best for governments to invest generally in education, basic research, infrastructure and other activities that benefit an industry cluster, and avoid picking individual corporate winners and losers. When incentives are appropriate, and sometimes they are, they need to be offered in a businesslike manner without melodrama.

As Amazon just showed everyone, corporations aren’t interested in local politics or serving as the local political football. That’s a lesson for any leaders who want to attract businesses and jobs, and for the voters who put them in office.

Steven Strauss, a visiting professor at Princeton University's Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, is an economic development specialist and a member of USA TODAY’s Board of Contributors. Follow him on Twitter: @Steven_Strauss

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Amazon lessons for voters, taxpayers, New York and the 237 other places that bid for HQ2