The Amazon's ancient complex of 'lost cities' flourished for a thousand years

A cluster of "lost cities" that flourished for a millennia have been discovered by archaeologists in the Amazon, with the findings published in the journal Science on Thursday.

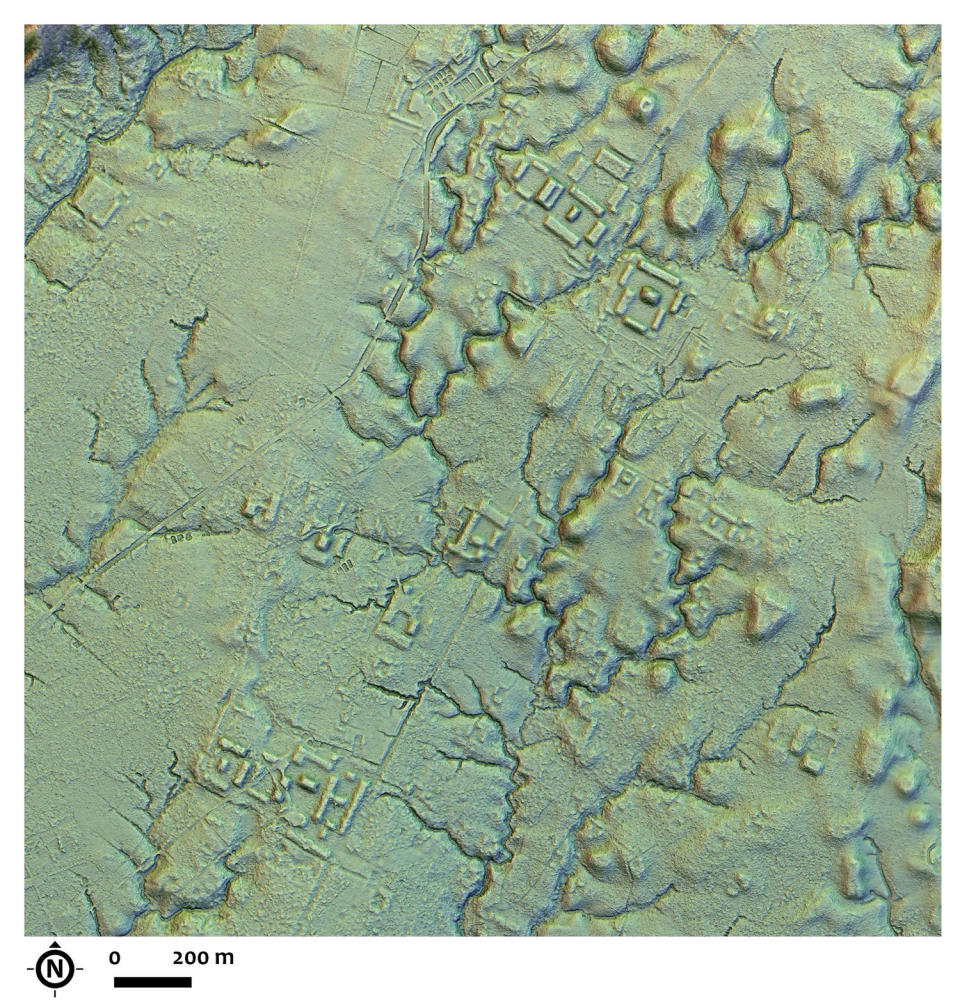

Laser imagery revealed intricate networks of roads, neighborhoods and gardens as complex as those built by the Mayan civilization.

The traces of the cities were first noted by archaeologist Stéphen Rostain at France's National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) more than 20 years ago, but “I didn’t have a complete overview of the region,” the told Science.

New laser mapping technology, called lidar, helped researchers see through the forest cover and map out new details of the mounds and structures in the settlements of Ecuador's Upano Valley.

The images revealed more than 6,000 earthen platforms distributed in a geometric pattern, connected by roads and intertwined with the agricultural landscapes and river drainages of an urban agrarian civilization in the eastern foothills of the Andes.

“It was a lost valley of cities," Rostain, who directs investigations at CNRS, told The Associated Press. “It’s incredible.”

The sites were built and occupied by the Upano people from about 500 B.C. to between 300 A.D. and 600 A.D., with the size of the population yet to be determined.

The team found five large settlements and 10 smaller ones with residential and ceremonial structures across 116 square miles in the valley, a vastness that put them at par with other major archaeological sites. The core area of Kilamope, one of the settlements, for example, is as large as Egypt's Giza Plateau or the main avenue of Teotihuacan in Mexico.

The landscape in the Upano societies could rival the “garden cities” of the Maya, where houses were surrounded by farm land, and the food consumed by most residents was grown in the city, the authors told Science.

The discovery of the Upano sites is so far “just the tip of the iceberg” of what could be found in the Ecuadorian Amazon, said co-author Fernando Mejía, an archaeologist at the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador.

The Amazon is considered the world's most dangerous forest, with dense, towering trees, tangled vines, hostile wildlife and poisonous insects. Archaeologists had believed it to be mostly suited for hunter-gatherers, but an inhospitable place for complex civilizations.

However, in the last two decades, scientists have found traces of human settlements in the Amazon, from Bolivia to Brazil, including mounds, hill forts and pyramids.

The newly mapped cities in the Upano Valley are 1,000 years older than the previous findings, including Llanos de Mojos, an Amazonia society in Bolivia whose discovery shattered what scientists previously believed about civilizations in the Amazon rainforest.

And details of the cultures of the two places are just beginning to unfold.

Carla Jaimes Betancourt, a German researcher who is an expert in Llanos de Mojos, told Science that the people of both the Upano Valley and Llanos de Mojos were farmers. They built roads, canals and large civic or ceremonial buildings. However, “We’re just beginning to understand how these cities were functioning,” she said, including the cities' populations, who they traded with, and how the societies were governed.

Rostain underscored how much there may be to uncover. “We say ‘Amazonia,’ but we should say ‘Amazonias,’ to capture the region’s ancient cultural diversity,” he said.

“There’s always been an incredible diversity of people and settlements in the Amazon, not only one way to live,” he added. “We’re just learning more about them.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com