America Has Always Tried To Be Hip-Hop’s Overseer

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

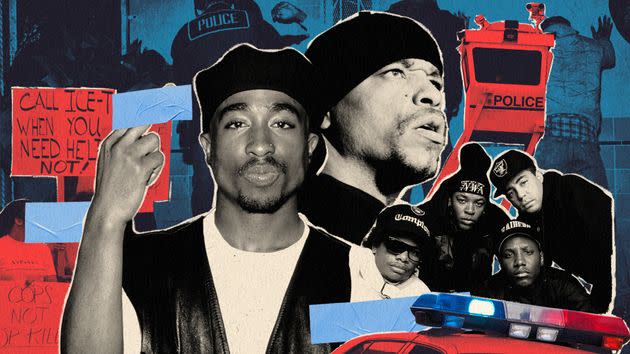

Maddie Abuyuan / HuffPost; Getty Images

Tupac, Ice-T, and N.W.A.

America Has Always Tried To Be Hip-Hop’s Overseer

In the early 1980s, when hip-hop was cementing itself in the Black community, so was a devastating new drug and a police force that didn’t know what to do with either.

By Phillip Jackson

Aug. 30, 2023

Let’s all jump in the whip and go back. Back to 2005, I was in the sixth grade, and the most popular hip-hop songs were still accompanied by dances. You know, Soulja Boy and all the other “crank dats” that would follow.

And while that music had its place, it didn’t have the substance I wanted. It didn’t feel like the CDs my father used to play during car rides when I was younger.

So, I started my own journey into hip-hop with Dr. Dre’s “The Chronic” and Raekwon’s “Only Built 4 Cuban Linx.” I was immediately a fan of the gritty and deceptive stories told from their on-the-ground eyewitness perspective, and the music was still relevant.

One commonality I found between the two iconic rap albums from the East and West Coasts was this unapologetic attitude and approach to telling what was really going on in their neighborhoods.

Through hip-hop, I would learn about war: The war between the Black community and the police.

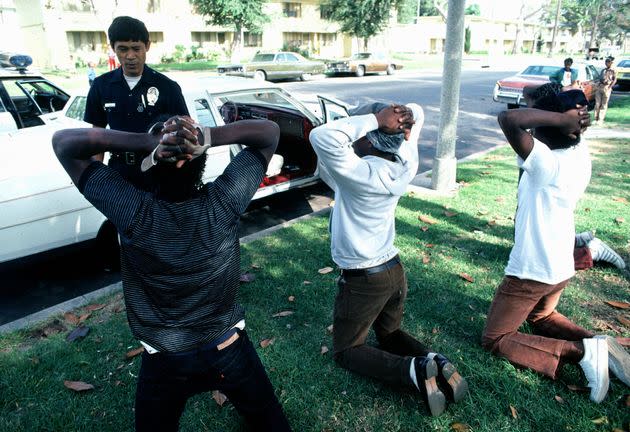

As hip-hop rose to prominence in the early ’80s, so did crack and, with it, violence. As the country declared a so-called war on drugs, they also declared a war on Black people and the music that was becoming the voice for the community. Rappers became journalists with raw and deep storytelling glorifying an inner-city Dickensian dream. No longer was the media a go-between for what was happening in drug dens. We no longer needed a Public Information Officer for an area’s drug task force. Ice-T could report exactly what happened at “6 ‘N the Mornin’.”

Los Angeles police search suspected members of the Rolling 60s gang for weapons and drugs during a sweep in south Los Angeles. The South L.A. area accounts for the largest number of street gangs in the nation, about 150 groups of mostly Black and Hispanic youths. Credit: Bettman/Getty Images

“Six in the morning, police at my door

Fresh Adidas squeak across the bathroom floor

Out my back window, I make my escape

Didn’t even get a chance to grab my old-school tape.”

With man-on-the-street narratives came the over-policing by neighborhood cops looking to get residents under their thumb. It would be two years after the protagonist in Ice-T’s rap ran from the police before America finally felt the wrath of young Black men in those communities who were tired of being harassed for merely existing.

In August 1988, the infamous and legendary hip-hop group N.W.A (Niggaz Wit Attitudes) dropped a few lines that forever cemented rap’s stance on police who grossly overused their authority when dealing with the Black community.

“Fuck the police comin’ straight from the underground. A Young nigga got it bad ’cause I’m brown,” the group rapped in their infamous single aptly titled “Fuck Tha Police.”

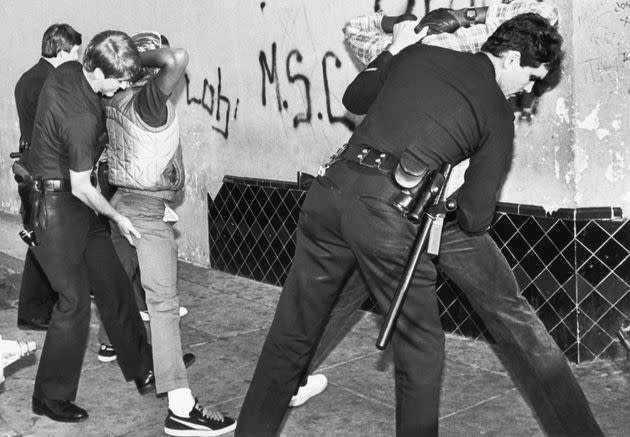

A "Crip" (left) dressed in blue, showing the Gang colors, is arrested by the Los Angeles Police Department anti-gang unit with two friends after stealing a Cadillac Car; a search turned up weapons and drugs. Oct. 16, 1984, Compton, South Central Los Angeles, California.

And just like that, the war was on. This line struck a nerve in the music industry and throughout America’s political landscape. Racial politics and police violence infused groups like N.W.A’s success, but it was only the tipping point.

During the late ’80s and ’90s, rappers highlighted the ills of dealing with the police when Black. There was KRS-One, who played with the word “officer” until it became overseer in “Sound of the Police,” Public Enemy with “Fight the Power,” Ice-T who shook the whole industry with “Cop Killer” and Tupac, who not only had a history of bashing the over-policing of Black folks in his music but even outside of his music he was never one to mince words when talking about or to cops.

After the fatal 1996 shooting of the rapper in Las Vegas, Chris Carroll, a Las Vegas Metropolitan police officer on the scene, had this to say (nearly 20 years later to a local news site) of Tupac’s response when asked who was the culprit behind his wounds: “And he went from struggling to speak, being noncooperative, to an ‘I’m at peace’ type of thing. Just like that … And that’s when I looked at him and said one more time, ‘Who shot you?’… I thought I was actually going to get some cooperation. And then the words came out: ‘Fuck you.’”

As these artists tried to share what was happening in their communities with the general public via their music, authorities began to eye them more — looking to end the messaging woven into their rhymes.

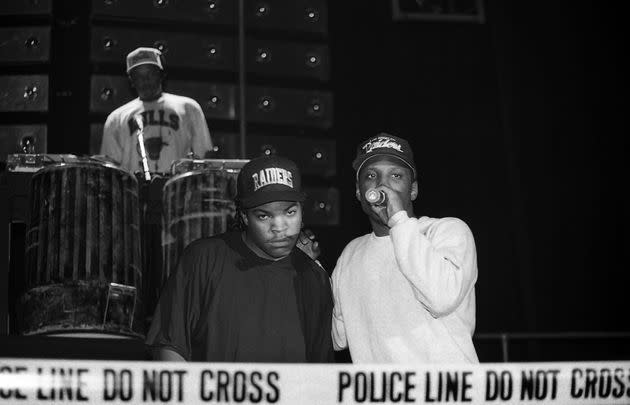

Rappers Ice Cube and MC Ren from N.W.A. performs during the 'Straight Outta Compton' tour at the Genesis Convention Center in Gary, Indiana in July 1989. Credit: Raymond Boyd/Getty Images

Detroit, Michigan, 1989

N.W.A is commanding the stage. The group attempted to perform their hit “Fuck Tha Police,” but they only made it through the first 30 seconds before they heard what sounded like gunshots.

Turns out the gunshot sounds were cherry bombs set off by Detroit police in an attempt to sabotage the group’s performance. The police were apparently afraid the song’s lyrics would incite violence. An example of police trying to control and withhold Black stories by attempting to keep their voices out of the mainstream.

And that was only the beginning.

The New York Police Department (NYPD) reportedly created a unit that rappers would label “hip-hop cops″ to keep tabs on rappers’ beefs along with their comings and goings. The NYPD would deny it, but Derrick Parker, a former NYPD detective, would later confirm that the Enterprise Operations Unit followed rappers in 1996. Parker, a hip-hop lover, also claimed he held a four-hour class for officers on beefs within hip-hop and the rivalry between East Coast/West Coast rappers. He claimed that 1997 NYPD cops were in Los Angeles when Notorious B.I.G was murdered. The city’s police also allegedly followed New York rappers without their knowledge.

Around the same time, then Death Row Records president Suge Knight reportedly hired off-duty LAPD officers to work for his label. Cops’ fingerprints were starting to smear all over hip-hop, and somehow, rappers began going to jail.

As a Black man, I’ve been skeptical of the unmoving microscope placed by authorities on some of my favorite artists who are simply trying to tell the stories that they lived.

Meek Mill performs as a surprise guest during Jay Z's set during the 2017 Budweiser Made in America festival - Day 2 at Benjamin Franklin Parkway on Sept. 3, 2017, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Credit: Kevin Mazur/Getty Images

Take the legal situation of Meek Mill, which posited a national discussion around criminal justice and bail reform after he was imprisoned for probation violations following a fight in 2017 and for doing tricks on his dirt bike later that same year.

First things first, harassing a person for poppin’ wheelies is just some petty-ass police behavior. Secondly, what was so unfortunately ignored by conservative contemporaries surrounding the Philadelphia rapper’s case was that the reason he was caught up in the American legal system stemmed from a classic and disappointing scenario of police brutality.

In 2007, Philadelphia police claimed that the then 19-year-old rapper pointed a gun at officers after being confronted for selling drugs to an informant. Mill claimed it was all bullshit and that he was arrested and brutally beaten by police. His mother even photographed her son’s swollen and bandaged face, for which a stylized version of the image was later used as the cover photo for his “Dreamchasers 4” mixtape.

“My mom took this pic and filed it with internal affairs, nothing happened!” he explained in a 2020 post on Instagram. “I been a rebel since!!! #georgefloyd I got charges for breaking one of the cops hands also like he didn’t break his hand on my face!”

And Mill isn’t the only rapper who has been caught up in the justice system.

Foxy Brown, Da Brat, Lauryn Hill, and Remy Ma have all served time. In 2005, rapper Lil Kim was sentenced to a year and a day in prison. The famed New York rapper was looking at 20 years for perjury and conspiracy after a shooting at a local radio station. According to Billboard, Lil Kim and her crew were leaving New York radio station Hot-97 (known as WQHT-FM) when they ran into Capone-N-Noreaga, also known as CNN, with whom they were beefing. Apparently, Lil Kim was mad over a diss from rival New York rapper Foxy Brown on CNN’s song “Bang, Bang.” A shootout ensued, and one person was injured. But because hip-hop is a truth-telling sport until you get pinched, Lil Kim claimed that she didn’t see Damion Butler or Suif Jackson, also known as “Gutta,” who had already taken plea deals at the scene of the shootout. Prosecutors seemingly couldn’t believe what they were hearing, considering both men were good friends of the rapper and had admitted to being at the scene. Oh, and Butler is also Lil Kim’s manager. But hip-hop doesn’t believe in snitching, so the “Get Money” rapper did what any good soldier would do. It’s twisted the way jail has become a resume builder in hip-hop, and the system, which is set up to hold Black bodies, doesn’t mind at all. In fact, it would prefer it this way.

Earlier this year, Young Thug and 27 others were hit with RICO charges. For those not up on game, RICO stands for Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, a law initially created to stop the mafia. Young Thug (Jeffery Williams), Gunna (Sergio Kitchens), Yak Gotti (Deamonte Kendrick) and Slimelife Shawty (Wunnie Lee), who all released music on YSL (Young Stoner Life) records were “hit with the RICO.”

Before RICO, a person could only be charged with an illegal activity that they’d done. After RICO, groups could be charged as interworking parts of a criminal empire; seemingly innocuous tasks could be considered illegal if there was proof that the task was a part of the larger group’s criminal activity.

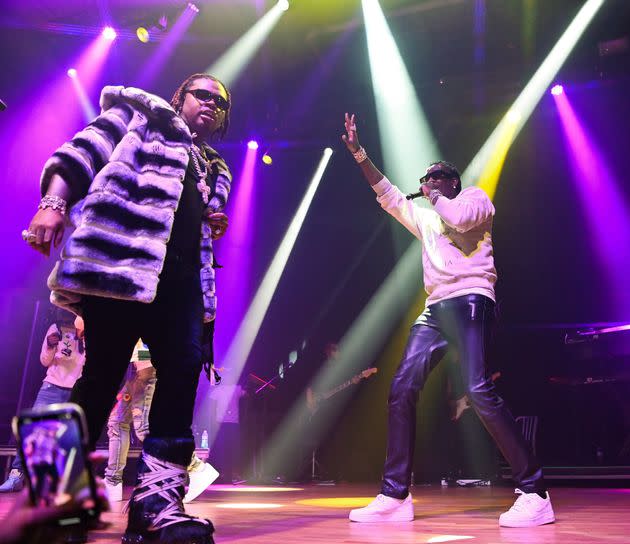

Gunna and Young Thug perform during Gunna Presents New Album "DS4EVER" Concert at The Masquerade on Jan. 15, 2022, in Atlanta, Georgia.

In the case of Young Thug, the indictment alleges he is a founder of a gang with the same name as his record label, Young Slime Life, also known as YSL. In May, the Atlanta rapper was charged with conspiracy to violate the RICO Act, gang activity involvement and more found in the 56-count indictment.

Some co-defendants, including rapper Gunna, have taken pleas, and 14 are set to stand trial.

What’s caused a national argument around the case isn’t the RICO charges, as clearly the police have constantly been policing hip-hop, but news that Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis –– yep, the same Willis who indicted former President Donald Trump on RICO charges –– is using the lyrics from the rappers’ songs against them.

“The indictment cites lyrics from nine Young Thug songs, including ‘Ski’ and ‘Slime Shit,’” Variety reports. “Several lyrics from the 2019 song ‘Just How It Is’ are listed, including ‘I done did the robbin’, I done did the jackin’, now I’m full rappin’’ and ‘It’s all mob business, we know to kill the biggest cats of all kittens,’ which the court deems in the indictment ‘an overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy.’ Also noted by the court is the 2021 song ‘Bad Boy,’ which includes lyrics like, ‘Smith & Wesson .45 put a hole in his heart / Better not play with me, killers they stay with me,’ and, ‘I shot at his mommy, now he no longer mention me.’”

Atlanta rapper Young Thug, whose real name is Jeffery Williams, speaks with his attorneys Keith Adams, left, and Brian Steel, right, at the Fulton County courthouse in Atlanta on Thursday, Dec. 15, 2022. He was indicted in a RICO case earlier this year.

This isn’t the first time the law has used lyrics as evidence, but music organizations are supporting the Restoring Artistic Protection Act (Rap Act), designed to protect artists’ freedom and creativity.

“Freddy Mercury did not confess to having ‘just killed a man’ by putting ‘a gun against his head’ and ‘pulling the trigger.’ Bob Marley did not confess to having shot a sheriff. And Johnny Cash did not confess to shooting ‘a man in Reno, just to watch him die,’” Congress members Jamaal Bowman of New York and Hank Johnson of Georgia, who introduced the legislation, wrote in a press statement, adding that the bill would “limit the admissibility of evidence of an artist’s creative or artistic expression against that artist in court.”

Gunna’s free, and Thug is still imprisoned, which means there’s been a hip-hop ruckus about whether Gunna committed one of the deadliest sins in hip-hop: snitching. Part of Gunna’s plea agreement was that he had to admit in court that YSL wasn’t just a record label but was also a criminal street gang. Doing so allowed Gunna’s release. That admission may prove damaging for the rest of the YSL members awaiting trial. It may also prove damaging for Gunna on the outside. Who knows. Some six months after he left jail, Gunna released “Gift & a Curse,” which addressed all allegations against him.

And I’m sure his fans and opps weren’t the only ones listening.

This story is part of a HuffPost series celebrating the 50th anniversary of hip-hop. See all of our coverage here.