How America’s Biggest Heist, the Great Brinks Robbery, Fell Apart

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

There are a few simple requirements for a crime to be considered perfect. It must be pulled off without any hiccups; it must pay off in some big way; and it must be untraceable, leaving the authorities puzzled about the whodunnit.

The Great Brinks Robbery of 1950 met all of these requirements—a great pile of cash disappeared with no evidence, leads, or suspects. Yet, it only amounted to a near perfect crime. The masterminds failed in one often overlooked aspect of the plan that has taken down many criminal comrades before and since: group morale.

Inside the Stringer Bell Bandit’s Bank Heist Spree

The 11 local thieves who banded together to rob the Brinks headquarters in Boston on January 17, 1950, were six days—six days—away from getting off scot free with what amounted to over $30 million in today’s currency. Then, one member of the group began to feel that he had been unfairly treated, and decided to bring the entire criminal enterprise tumbling down.

In the late 1940’s, local criminal and ne’er-do-well Tony “Fats” Pino got an idea. The Sicilian native made a name for himself in the Boston underworld and with Massachusetts law enforcement for his burglary skills. When he discovered that all the money collected around the city by Brinks came through their North End headquarters every evening, he became obsessed with a new mission.

What if he pulled together a small crew to rob the Brinks building one evening when the city’s haul for the day was in residence? Queue a midcentury romp straight out of the Hollywood heist playbook.

Pino took his idea first to Joseph McGinnis, a bigwig in the Boston underworld, who agreed to join the new venture. They then assembled a crew of nine other co-conspirators who each brought their own skills and rap sheets to the gang.

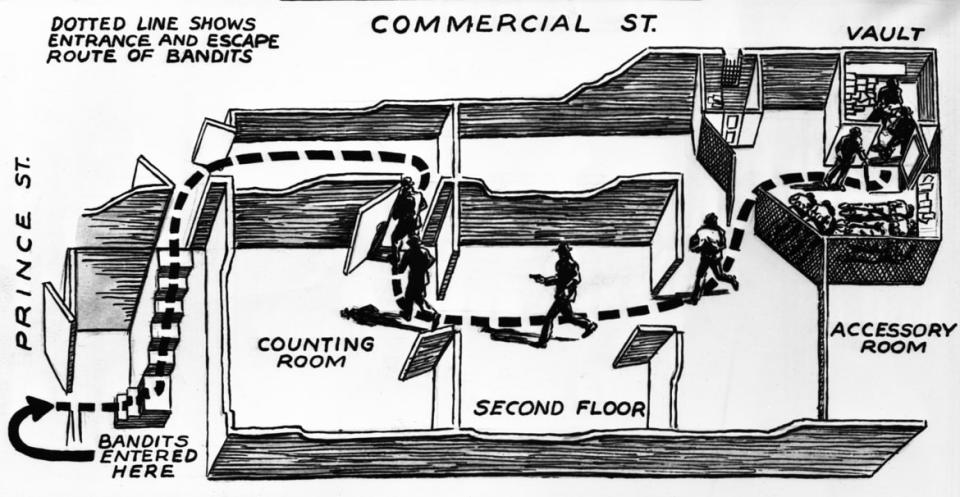

For nearly two years, Pino meticulously planned the heist. His crew conducted thorough surveillance on the building, tracking the movements of the trucks, guards, and their loot. They got a copy of the alarm system plans (by robbing the alarm company, of course). When they discovered that the money was secured behind a series of locked doors, they went about breaking into the building over several nights and stealing one lock after another.

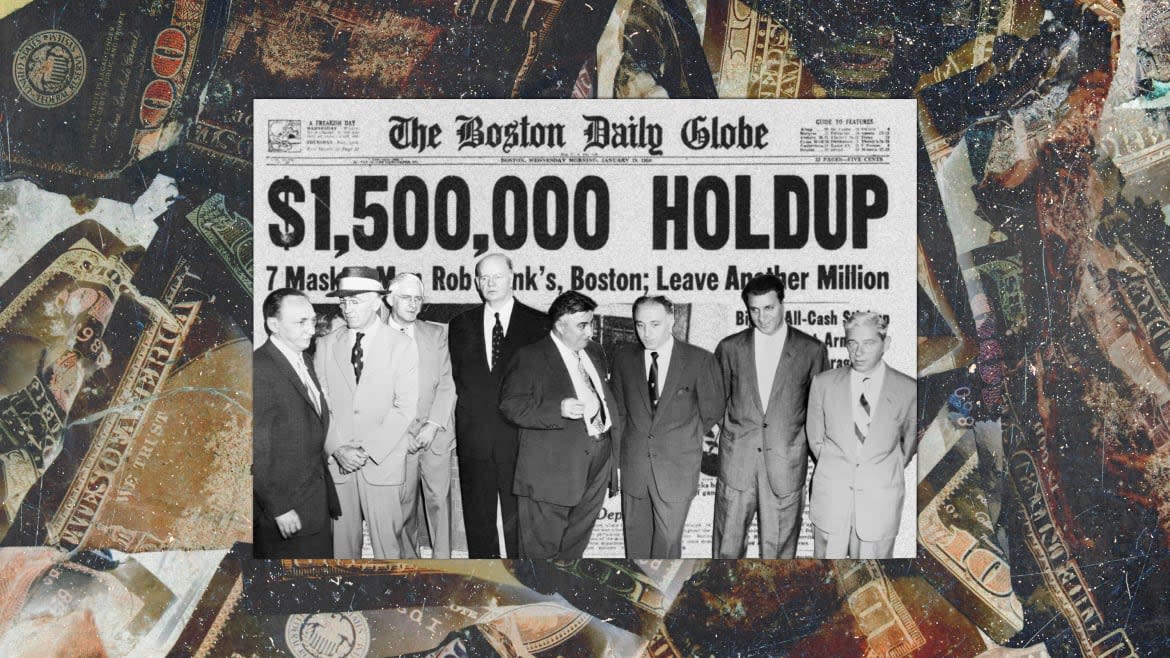

Anthony Pino, 48, is taken from the local FBI headquarters for arraignment in 1956 in connection with the Brink's robbery.

While each lock was in their possession, they would make a copy of the key, then put the original lock back in place before the morning crew arrived. They conducted dress rehearsals to run through every move of the plan. The timing had to be meticulous, after the last delivery of the day, but while all of the guards were counting the money before securing it for the night.

As the big day neared, they put together the perfect outfits that, at a glance, could be mistaken for Brinks uniforms. The seven guys chosen to enter the building during the robbery wore navy peacoats, chauffeur caps, and gloves. They disguised their faces with rubber Halloween masks and “to muffle their footsteps, one of the gang wore crepe-soled shoes, and the others wore rubbers,” according to the FBI.

“It was an adventure,” John Adolph “Jazz” Maffie, a member of the crew, told The Washington Post in 1978. “Pino kept telling us the money was in there, he never stopped. It's hard to explain but it was exciting, we were younger, of course I wouldn't do it now.”

They took their time and didn’t rush their preparations, but finally the day arrived. Everyone took their places—seven men donned their disguises to enter the building, two (including Pino) took their place as getaway drivers in a stolen truck, and one man made his way to the roof across the street to serve as lookout. The only one who stayed away that night was co-ringleader McGinnis, who spent his evening dining out in the presence of a Boston police detective as part of the crew’s alibi.

They waited for the last truck of the day to arrive and unload, and then, just before 7:30 p.m., the lookout signaled that it was time.

The seven men silently entered the building, disarmed the alarm system, unlocked the doors with their keys, and crept into the main room with guns raised. They took the five Brinks employees completely by surprise.

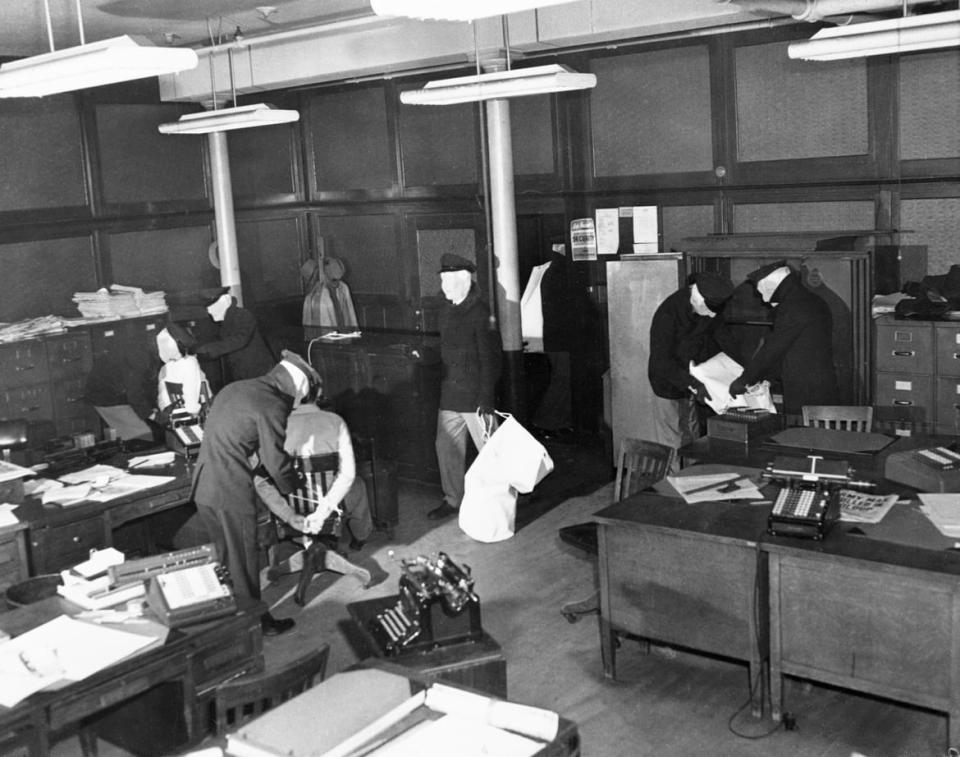

A reenactment of the Brink's robbery in 1950.

Pino’s crew worked quickly. In under 30 minutes, they had gained entry, secured the Brinks men, taken all of the cash ($1,218,211.29) and checks and money orders ($1,557,183.83) that they could carry, and then were spirited away in the waiting truck.

Within minutes after they left, police arrived at the scene, but there was no trace of the culprits. The only evidence they left behind were the ropes and gags that still bound the Brinks employees and one chauffeur hat. The rest of their disguises were later delivered to McGinnis with the truck and were burned.

After that, the gang divided up the loot and dispersed. They had agreed ahead of time not to spend the money for six years, which at the time was the statute of limitations within which they could be prosecuted for the crime.

An artist's diagram of offices of the Brink's showing how seven masked gunmen entered the building and confronted five employees and made away with $1,500,000.

The heist was a huge success. It was the biggest robbery to have been pulled off in the U.S. up to that point and it made front pages across the country. It was so big that the FBI was immediately called into action.

For nearly six years, rewards were offered and leads followed. The FBI tried to trace the money, keeping an eye on race tracks, casinos, and resorts where men of previously modest means might be suddenly seen spending a fortune. Over the course of their investigation, they spent $29 million trying to solve the $2.7 million robbery, according to the Washington Post. But they were getting nowhere.

They rounded up the usual suspects, of course. Some of these included actual members of the team and known underworld figures like McGinnis. But the Brinks gang had planned for this and had their stories and alibis straight. Without any evidence to connect them to the crime, law enforcement had to let them go.

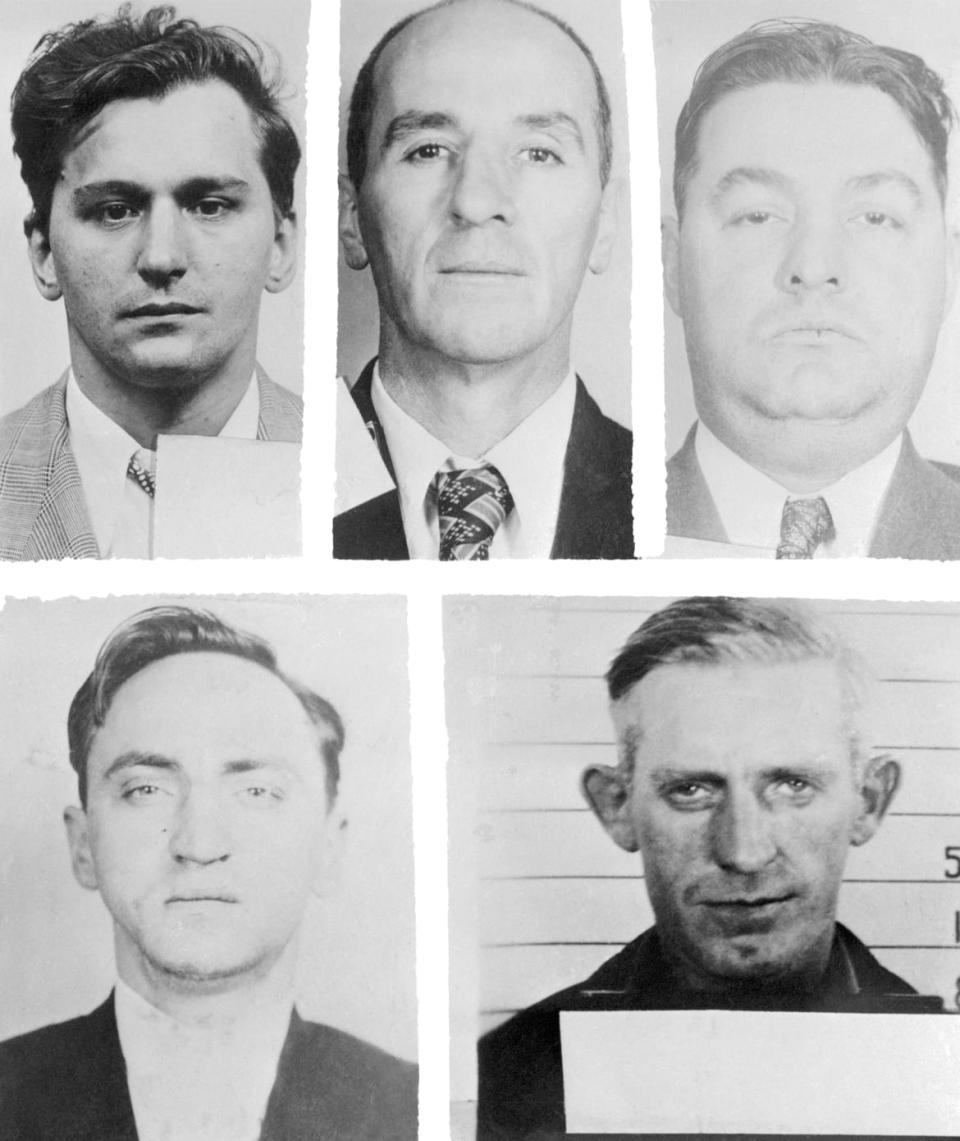

Brink's robbery perpetrators (L-R, top) Stanley Albert Gusciora, Joeseph James O'Keefe, Joseph Sylvester Banfield. (L-R, bottom) James Ignatius Faherty, and Thomas Francis Richardson.

“In the hours immediately following the robbery, the underworld began to feel the heat of the investigation,” reads an FBI article on the piece. “Well-known Boston hoodlums were picked up and questioned by police. From Boston, the pressure quickly spread to other cities. Veteran criminals throughout the United States found their activities during mid-January the subject of official inquiry.”

Back in their Boston neighborhood, the gang might not have played the part of Robin Hood, but their crime was not condemned, either. They had successfully taken an almost inconceivable amount of money without firing a single bullet.

“It wasn’t like the robbers knocked off the local church or the local orphanage,” Stephanie Schorow, author of Crime of the Century, told WGBH. “They picked a big company that could afford—in the minds of many—to lose this money so people took a perverse pride in it.”

Six years was not a long time to wait when millions were on the line, and everything seemed to be going according to plan. But then, division in the ranks began to spread.

The problem child of this little posse was Joseph James “Specs" O’Keefe. He spent his time waiting out the six years doing what he did best—crime. His activities landed him in and out of jail.

As he racked up expenses for his defenses, he became increasingly anxious about getting his hands on his share of the money. Because of his legal troubles, he had left his portion in the care of several of his Brinks comrades. The first time he got it back, he claimed it was $2,000 short. After another prison stint forced him to entrust it with his colleagues yet again, it was lost for good. This time, he said Maffie claimed part of it had been stolen and the other part had already been spent on his defense.

FBI agents and Boston police seized between $70,000 and $90,000 of the Brink’s robbery loot in a raid on the B&P contracting company in Boston’s South End in 1956.

And here is where things began to go off the rails. In retaliation for the perceived theft, O’Keefe, who had been brought in as one of the “heavies” of the group, began to put pressure on the others. When that didn’t yield any funds, he kidnapped Pino’s cousin, who had also been part of the crew, in May 1954 and held him captive until the boss finally paid the ransom he demanded.

O’Keefe’s behavior was causing everyone anxiety, but this was the last straw for Pino. Over the next month, O’Keefe survived three assassination attempts, the last of which was committed by a known hitman. He suffered only minor wounds and soon ended up in jail again. While he was locked up, a friend of his who had helped him put pressure on the gang went mysteriously missing, suspected to have been taken out by Pino’s men.

O’Keefe had stayed religiously tight-lipped during every previous encounter with the FBI, but this time when the feds approached, he decided to talk. He was facing a long time away and by this time held only bitter feelings towards his co-conspirators.

For three days starting on January 6, 1956, O’Keefe told all. Based on his testimony, charges were issued on the 11 members of the Brinks gang just days before the statute of limitations ran out.

All of the thieves either served time or died before their cases made their way through the legal system. So, justice was eventually served…mostly.

While every single detail of the plotting and execution of the Great Brinks Robbery is known thanks to O’Keefe, there is one major aspect that remains a mystery. To this day, only around $60,000 of the stolen money has ever been recovered.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.