America’s largest mass shooting is the one happening every day. But we know how to stop it

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the neighborhood, they called him Tree.

Taronn Sloane grew up in the Tilden Houses projects in Brooklyn. The adults in his life passed, one by one, so he and his siblings mostly had to fend for themselves. He got by, robbing people and slinging drugs. That got him two trips to Rikers Island.

When he came home from prison, he was ready to be part of the solution instead of the problem.

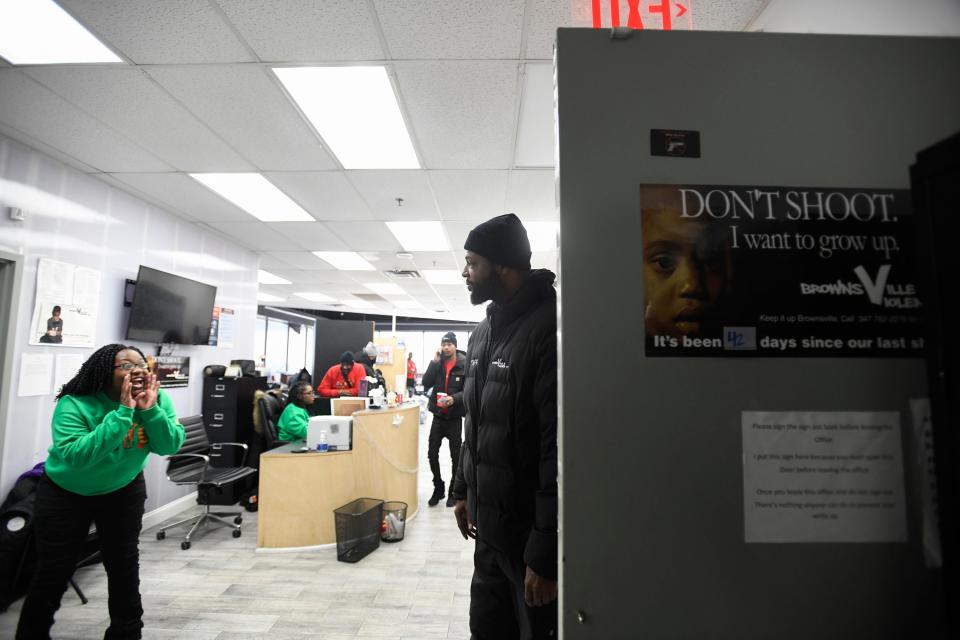

He ended up a mentor with the group Brownsville In Violence Out. He became the kind of person you call a violence interrupter.

Many of these people are former gang members and reformed criminals. They know what it takes to put others on a better path. They defuse conflicts before things turn violent, watching the streets for trouble and heading it off.

He was the kind of person I call a neighborhood hero. They called him Tree because he was 6-foot-8. But his nickname could have been interpreted in the literal sense: an anchor. Roots. He was someone who helped keep kids alive.

And on that night in January when he saw the man in the stairwell wearing a ski mask, he knew something wasn’t right.

He tried to read the body language. He tried to warn the young men in the building. Then the man raised a gun and shot, one time.

If this story is starting to sound familiar, that’s because it is. There’s a funeral for someone like Tree happening somewhere in America every day.

I spent this year writing about these people, in cities across America. They work to stop gun violence in their own communities, only to become victims of gun violence themselves.

At first, the tragedy of the coincidence shocked me. The path of each bullet was one version or another of a one-in-a-million chance.

But in America, a shooting victim will never be one in a million. They’re more like one in a hundred – the more than 100 people who die from gun violence every day.

Nobody I wrote about was killed with an assault rifle. None of them ended up on a mass shooting list. But make no mistake, each one of them was part of a mass shooting – the daily mass shooting that happens across America.

So I wrote intentionally about people who had been murdered with handguns, because they are the weapons that kill the most. Intentionally about people who were Black and brown, because they are the ones who die in disproportionate numbers.

For every neighborhood hero who died, with every story I wrote, I wondered and worried a little more: How will we ever solve this problem, this uniquely American contagion? I wanted to give up. I didn’t because I knew they wouldn’t give up. They would get up and keep trying.

I knew this because, while each one was different, they were also all the same. A 43-year-old football coach. A 23-year-old entrepreneur. A 46-year-old grillmaster. Each one was a coach, a mentor, a friend who built a community and died in that one-in-a-million shot.

Tree was the same, too. The only thing different about his story is how it ends. He lived.

Don’t let it go to waste

Tree has lived in the same New York apartment his entire life. As a kid, getting outside was his safe haven. But first he had to go to church. Grandmoms' orders.

At one point, the three-bedroom flat held 13 people, and sometimes a long line for the one bathroom. It was Tree and his three siblings; his grandmother and grandfather; an aunt, her husband and her four children. His mother dipped in and out, depending on her stage of drug and alcohol dependency.

All of those people are dead or have moved on now, save for Tree and his youngest sister, a 33-year-old who has autism.

His mother had HIV and died in 1997. Tree was 10. His father, who reappeared in his life after his mother died, followed her a few years later – he also was HIV-positive. His brother, nine years older, “kept me alive,” Tree says.

That big brother died in 2000 from a brain aneurysm. His older sister died in July from a heart attack.

Tree was a promising basketball player until he dropped out of school at 16 when he became a father.

“I thought I was grown, out here having kids,” he tells me. “So it became: Bounce a basketball or your daughter needs Pampers. It became: My daughter needs Pampers and this basketball isn’t going to give me those Pampers right now.”

High school soon became an afterthought; he instead walked or took the bus to his girlfriend’s house to help care for their newborn.

At night he would rob people. That got him four months on Rikers Island as a juvenile. He tried to live right when he came home, but the need for fast cash was always there, and the lure was unmatched. He started slinging drugs. He returned to Rikers in 2014, as an adult, with a two-year sentence for narcotics trafficking.

He came home from prison in 2016, back to Brownsville, considered Brooklyn’s most dangerous neighborhood. In time, only his grandmother was left. She got sick, and on Jan. 25, 2021, she was gone.

He became the head of the household, now responsible for his younger sister and the family cat, Brooklyn. It was the final push he needed.

He linked up with Brownsville In Violence Out, BIVO. Like his colleagues – he called them his brothers and sisters – Tree subscribed to the mantra: Once part of the problem, now part of the solution. Stop violence before it starts.

His mission became serving as a big brother, someone who helps to keep the younger generation alive.

Tree robbed people and sold drugs. I know that in another version of this story, he would have been an easy argument for harsh punishment, longer sentences. But here’s the thing about the men I wrote about this year: They knew all these things can be connected.

Some of them devoted their lives to kids because they could see how easy it was to fall onto the wrong path. Some of them, like Tree, know because they were on it themselves. They know you can find a way out, if somebody shows you.

“To be honest, I do this – even when I wasn’t with BIVO – just trying to keep the kids on the right path,” Tree tells me. “How these kids are growing up is totally different from how I grew up. Outside to me used to be a safe haven. It was more of a community, and everybody had a hand in your life.”

When he was not working, Tree was usually in that family apartment playing video games. That’s where he was on that night in January this year, deep in a PlayStation NBA 2K battle with online friends. He got hungry around midnight and decided to make his regular Popeye’s run.

The man in the ski mask was standing in the stairwell near the exit door as soon as he opened it.

They both jumped, startled. Tree didn’t have a good feeling. As he walked away from the building, he couldn’t stop thinking about it. He got on his phone to warn the young men who often hang in his lobby. He wanted to tell them: There’s somebody who doesn’t belong and they look suspicious. No one picked up.

Tree returned with his food about a half-hour later. He saw the young men – he calls them kids – in the lobby and told them: “Be careful out here.” As he started up the stairwell, he saw the man again.

Tree was holding a bag with a spicy chicken breast and macaroni and cheese. The other man was holding a gun. No words were exchanged.

“As I looked up, he just shot one time,” Tree tells me.

The bullet tore through the right side of his chest and exited his right lower back. He tumbled down the stairs, screaming in pain before starting to convulse.

When I talk to Tree about what happened next, what he remembers are the voices.

It was Jan. 25. The same day his grandmother died.

“All I kept hearing was my Grandmoms in my head, saying: ‘You’re going to be OK. You’re going to be OK,’” he says.

He tells me about the spot where the bullet hit – on his upper chest.

“Where I got hit at, when I stand next to most people, that’s where their head is at,” he tells me. His height might have saved him from a head shot.

The medical team that worked on him at Brookdale Hospital saw it another way. Instead of Tree, they nicknamed him Wolverine.

“The doctors kept saying: ‘You’re a blessing. A lot of people that come in here and get shot where you got shot at normally don't make it,’ Tree says. “They told me, 'Whatever God’s got planned for you, just don't let it go to waste.’”

A city’s worth of solutions, or more

We know what happens when we talk about mass shootings. Polls consistently show a majority of Americans support some form of additional, sensible gun safety measures. After a shooting with mass casualties, after we get past the thoughts and prayers, Americans speak up, demanding action. And then we go back to our little worlds until the next one. Rinse and repeat.

But a lot of shootings happen like Tree’s shooting. On the street, one at a time, in cities big and small. People notice, but not enough of us do.

There’s something we can do about that. Just ask the people in the cities.

“Congress should pass additional gun regulations that will protect our communities from massive mass shootings,” Regina Romero tells me when I call. She’s mayor of Tucson, Arizona. She’s also a co-chair of an initiative called Mayors Against Illegal Guns (MAIG), an outgrowth of the gun violence prevention organization Everytown.

But it’s not just about mass shootings, she says. It’s about the everyday toll.

She and her co-chairs know nobody else is coming to save them. In many states, including Romero’s, state legislatures bar cities from taking the steps they want to take to slow gun violence.

Earlier this year, Philadelphia filed a lawsuit seeking the power to pass its own firearms laws. In Pennsylvania – as in more than 40 other states – state law bans cities from making any local gun rules that are tougher than statewide law. The city says that law deprives Philadelphians of their right to life and liberty. The state Supreme Court has yet to decide whose rights are more important.

“We need the cities and the states – every layer of government – to have a strategy and a focused approach to tackle the reasons why this is happening,” Romero says. “It's going to take all of us.”

Some states are trying. I went to Seattle to look for the spirit of a man who started his work as an activist calling for an end to school shootings, and I found an echo of him in the records of the state Legislature. Just after he died, Washington state passed an assault rifle ban – a direct response to school shootings. But that law may soon be upended in the courts.

That’s what happened in California. I went to Wilmington in the footsteps of a man who dedicated his life to keeping kids out of gangs, only to be killed by a single bullet in a city park. Two months later, the governor signed a law banning guns in public places like that park. But just last week, a federal judge blocked it from taking effect.

Even when voters speak at the ballot box, the fight is lost in court. Last month, an Oregon judge ruled against a 2022 voter-approved law that requires permits, bans large-capacity magazines and creates a firearms database. The judge called the ballot measure unconstitutional.

In Baltimore, federal limitations sting. Mayor Brandon Scott would like to stop the flood of illegal guns that washes into his city. But the Tiahrt Amendment prohibits the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives from releasing firearm trace data for use by cities and requires the FBI to destroy records of approved background checks within 24 hours.

“We've already seen close to 2,700 illegal guns in the city this year. That's a 9% increase over last year. And we know that over 60% of them come from other places,” Scott tells me. “Until Congress gets their heads out of their behinds and takes out the Tiahrt Amendment, local governments and mayors will not be able to have a deeper impact on gun violence.”

Guns also remain the leading cause of death for children and teens because of both homicides and suicides. The rates are much worse for children of color.

“The age of the assailants is heartbreaking,” Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas tells me. “The age of victims is heartbreaking.”

“I think the biggest problem we have right now is that we are still fighting gun violence through a 1980s prism,” says Lucas, who laments that his city is on pace to reach near historic levels of gun homicides this year. “We are thinking about them through organized gangs. … Frankly, the world is drastically different.”

The gun tally is increasing. The death toll is increasing. The solutions are being blocked.

It’s enough to make us give up hope: About 60% of Americans say they believe gun violence is a major problem. And that same percentage expects it to get worse in the next five years instead of better.

But then I think about the neighborhood heroes. Every death is part of the same tragedy, but every shooting is different – whether it’s a random bullet, a road rage confrontation, a turf war or a school massacre.

Perhaps that’s the story that gets missed. There is no one version of the crime. So there is no one solution.

That’s why we have people like Tree.

The real answers

After the shooting, Tree slept fitfully, often waking and reliving it, visions of a gun pointed at him. When he took out the trash, he would shudder at the stairwell exit door he was forced to pass.

Still, he returned to work two weeks later, a little shy of Valentine’s Day.

Yes, Tree went back to work, back to the streets, back to looking for trouble and for the troubled. Because that’s what neighborhood heroes do.

New York Mayor Eric Adams visited Tree at his hospital bedside as he recovered. And on March 6, Adams honored Tree by declaring it Taronn Sloane Day.

Tree, now 36, doesn’t know for sure why he was shot. He heard there had been a shooting earlier that day in his complex, and he wonders if the man in the ski mask was looking for revenge. “I think they shot at him earlier, and he was trying to get his get-back,” he tells me.

A 23-year-old suspect was arrested and is awaiting trial.

“I know that most people who would have got shot would want revenge,” Tree says. “But I look at that kid as another lost kid.

“I wouldn’t want nobody to give up on me. By me still giving them that hope, I can look back and say, ‘I always gave people a chance to do right for themselves.’”

Tree says there is no village anymore. Those grandmothers and uncles and neighbors who kept us in line when we were young. Those who had a hand in every aspect of our lives. But I don’t agree. See, I found the village.

In Indianapolis, a man named Richard Donnell Hamilton once told me: “People have guns. The wrong people have guns.” So he coached a generation of young boys to point them to the football field instead of the street.

In Seattle, Elijah Lewis first raised his voice to tell lawmakers, “Think about your children.” He helped pitch hundreds of people to sign on to a pact he called the Covenant: “We work together to protect our community.”

In Southern California, Jose Quezada taught kids to play sports – the same way a man in the neighborhood had once taught him – because sports keep you on the right path. “I bless to be blessed,” he said. “God looks after me because of what I do for people.”

Sadly, those stories came only after their funerals. And there’s a funeral for somebody like these men happening in every big city in America. I have been to too many.

But I refuse to believe the realities that exist now must exist forever.

I’ll say what our elected officials often dance around. We’re never going to be rid of guns. It’s not possible. There are just too many and they are too accessible. Guns are pervasive; that genie isn’t going back in any bottle.

That doesn’t mean we should give up on changing things. Wanting to see children survive and grow into adulthood is not a political position. It’s a moral one. Legislators, governors, representatives and senators, are you listening?

And the fact that those people are failing us doesn’t mean we get to throw up our hands in defeat. It doesn’t mean we can’t mentor and coach and teach. There is no one version of the crime, so there is no one solution. There are many.

It will take neighbors, family and friends to hold others to account, to check and uphold our forgotten societal codes. It will mean taking responsibility for those under our roofs, and those who are strangers.

Ask the people in the cities. They know.

“I believe that our police department is a big part of helping us, but they should not carry the burden of our own societal ills that we have refused to attend to as a society,” Romero tells me from Tucson.

“Real men don't just stand by and watch younger men, and people's families, and women and children get shot in this city and sit on the sidelines,” Scott tells me from Baltimore.

“I want to be very clear,” Scott says. “We have these right-wing folks and others who are trying to simplify what's happening with gun violence in the city – it has to be some ‘drugs and gangs’ thing. This isn't that. Interpersonal violence is driving what's happening; basic human conflict. Individual action by people who are credible with those people can save those lives.”

State laws, city ordinances, better education, resources and economic equity will all help. But it all starts with each one of us doing our part. Talking. Guiding. Coaching. Mentoring. Tutoring. Listening. Caring.

When I started learning about Elijah Lewis in Seattle, somebody pointed me toward his best friend, Edd Hampton Parks. I knew it would be difficult, but I asked him if he would tell me everything he could about Elijah.

He agreed, but he asked me, “Why does USA TODAY care about this?"

In the moment I heard that question, I understood clearly what he meant, just as clearly as I could feel my own heart breaking.

Of course this Black man had to wonder why a big national newspaper wanted to write about his best friend, another Black man, in a way that celebrated everything that was right about them.

I took a deep breath and gave Edd the best answer I could. “Because I care,” I said. It was a place to start.

There’s a neighborhood hero in every city and on every corner and in every stairwell in America. We have far more of them than we see, yet not nearly as many as we need.

So like each of these men, we must refuse to give up hope. Every one-in-a-million shot can be stopped – by just one of us.

Suzette Hackney is a national columnist. Reach her on Twitter: @suzyscribe.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Gun violence: They knew how to solve the problem. Are we listening?