America’s mayors hold the keys to the post-COVID recovery

Dear America’s Mayors,

I expect you’re getting a lot of advice right now. Possibly for the first time in many years, your city may be flush with cash, and everyone—your staff, your City Council, your Chamber of Commerce or Tourism Department, passersby on the street—has ideas about how you should spend it.

My advice: Don’t.

Or at least: Don’t spend it until you’ve thought about what got us here. I’m not talking about COVID-19—I’m talking about the principles, policies, and practices that created the need for a recovery in the first place.

Between your American Rescue Plan allocations, better-than-expected tax revenues, and potentially big bucks from the bipartisan infrastructure bill, you have the resources to really think and act big right now. The options before you are practically overwhelming, as is the political pressure you’re going to face to get it right.

Don’t be daunted. This is a moment of unparalleled creativity and opportunity for America’s cities. As a mayor, you have a chance to build a legacy for yourself and your community that could last for generations. Doing that will take some patience, political imagination, and the courage to ask some tough questions about the way you currently do business.

We know where this isn’t happening. In Urban3’s hometown of Asheville, North Carolina, for instance, city officials are proposing to plug a budgetary hole with $7.5 million of ARP money to prevent a water bill hike. Politically speaking, it’s a savvy play—what politician wants to raise taxes when buckets of federal dollars are sitting in front of them? But if we don’t reckon with the flawed choices that made our water system so costly to maintain in the first place, we’re just financing more fragility. Uncle Sam won’t be giving us another $7.5 million anytime soon.

New storm water and sewer projects don’t generate sexy headlines, but they do qualify under the Treasury Department’s complicated rules for how ARP dollars can be spent. Navigating those will be its own form of direct aid to the nation’s lobbying class.

Unfortunately, in a lot of places, this will result in a lot of money being flushed down the toilet. South Bend, Indiana, is one such example. Even though their population has fallen since the late 1960s, city officials have never stopped building out their water infrastructure. As of today, if you laid all 611 miles of their pipes end-to-end, they’d stretch all the way to Asheville. This infrastructure is aging, and maintaining it gets more expensive every year.

I can’t tell you what to build in your city, or where, or how. That’s actually my whole point, so here are some recommendations I can offer:

Stop chasing growth. Like a lot of cities, South Bend has learned the hard way that when a suburban housing developer tells you a project is going to generate “growth” for your market, it’s actually probably going to bury a financial landmine in the sprawl for future generations of taxpayers to step on. To their credit, South Bend has now stopped building sewer lines to nowhere. Other cities can learn from their decades of mistakes.

Value might be hiding in plain sight—but you still have to look for it. Or at the very least, look at it. Cities are property developers, but often have no idea how to value what they own. As a result, public assets go undervalued and their development potential goes unrealized. This includes land that is wasted on surface parking. Every single city where we have conducted a public asset valuation, like in Pittsburgh, we uncovered billions of dollars in value and new development opportunities. Speaking of development...

Be agnostic and diagnostic. If we think of urban policymakers as physicians, their first duty is to do no harm. You can use simple geographic information system (GIS) technology to make an “economic MRI” (a term which we have trademarked) of your city to see where you are spending money and failing to get a return on that investment.

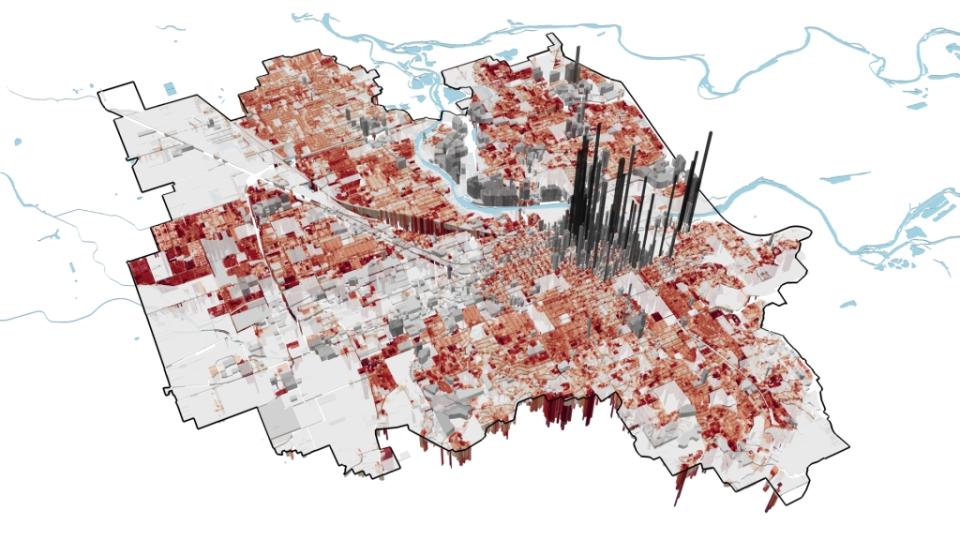

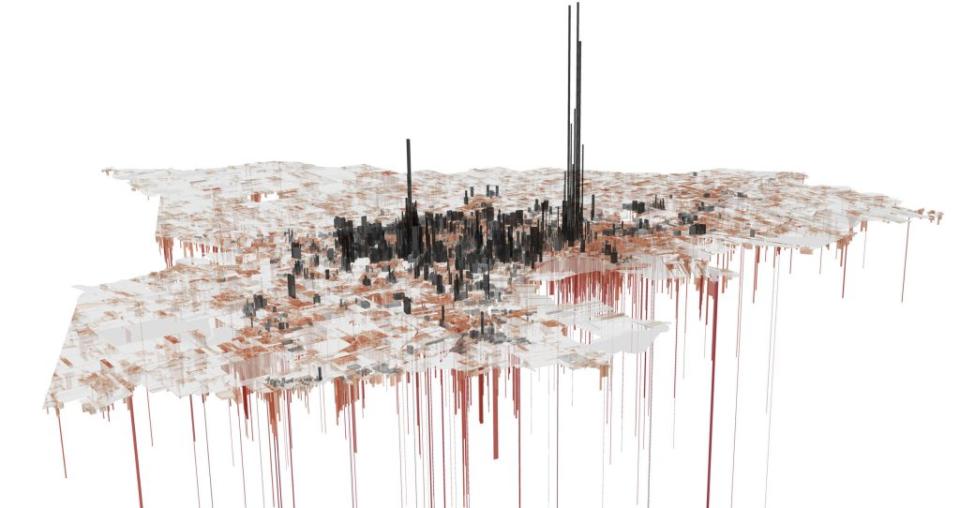

Take cities as diverse as Eugene, Oregon and Lafayette, Louisiana—two of the many cities where our firm has conducted an economic MRI. When you do the math to see what every parcel in their city is generating in terms of tax revenue, and then make it visual, you see some clear peaks and valleys, as measured in the graphics below.

Those black spikes on the maps aren’t buildings, per se—they are dollars, representing the value per acre created in that part of town. These parcels are net positive assets for the city, insofar as they simply generate more revenue in property taxes than they cost to maintain.

In traditional downtowns—dense, walkable built environments with lots of older buildings and mixed uses—value will be high.

And where the map is redder and lines are bleeding through the bottom? Those parcels are costing more for the city to maintain than they generate in property taxes.

Does that mean the whole city should be made over to look just like downtown? Of course not. It does make the case, however, that any investment in a more walkable, less auto-dependent development pattern, you’re building in a more fiscally responsible way. That will have tax implications for your residents and businesses for years to come.

America’s cities and counties have an obligation not to return to the bad behavior and irrational choices that made so many of our metro areas so fragile when the pandemic struck. We believe that begins with taking a hard look at your city’s finances and modeling your revenues and expenses geospatially. These maps can also inform citizens about the financial realities every city faces.

If you’ve been subsidizing a less productive building pattern in your city, especially without calculating the eventual maintenance costs to taxpayers, there is no better time than right now —using the dollars the federal government has given you—to start making better choices. Before you put that money to work on any new capital project, make sure you know how much you’re on the hook for over the long term. The long term is always here sooner than you think.

Cities that can find the courage to stop, reconsider their previous choices, and ask the tough questions about how to move forward will be much more competitive and resilient in the future.

If you choose not to ask these questions and do these things—if we repeat the mistakes of the past—no amount of relief or rescue dollars will ever be enough to let us build back in a better way.

Sincerely,

Joe

Joe Minicozzi is the founder and principal of Urban3, a consulting firm specializing in land value economics, property tax analysis, and community design.

More must-read commentary published by Fortune:

A stronger Earned Income Tax Credit will help Americans weather an era of crisis

“Fauxquisitions” are misleading the startup community

To protect American innovation, we must let websites keep moderating their own content

After a backlash summer, ESG needs to get back in the game

We are reinventing the toilet to prevent the next pandemic

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com