'Our American way of policing is on trial': Law enforcement officers respond to Chauvin trial

As he prepares for work each morning, Tighe O’Meara, the police chief in Ashland, Oregon, tunes in to coverage of the trial of Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis officer charged in the killing of George Floyd last year.

O’Meara doesn’t watch to decide whether he thinks Chauvin is guilty; he sees Chauvin’s culpability as “an open-and-shut case.”

He watches for signs of hope for his profession.

He found some in Chauvin’s former colleagues and bosses who broke the so-called blue wall of silence to testify against him. “We need as much of that as possible,” O’Meara said in an interview this week. “We need transparency and integrity above all else.”

But O’Meara, who is white, also sees the trial as a test of whether police can regain the trust of many Americans, most of all the Black and the Latino residents who disproportionately live in high-crime, highly policed neighborhoods.

“If he’s convicted, it will be a strong declaration that we as a society hold police officers to account for their actions,” he said. “If he’s acquitted, it will be an event that takes us in the exact opposite direction.”

When Michael Persley, the police chief in Albany, Georgia, watches the trial, he sees the profession he loves at a crossroads. As a 28-year law enforcement veteran, he says, the trial is a reminder how damaging Floyd’s killing was for policing — and a lesson for his officers to follow use-of-force policies. At the same time, he is a Black man who understands why Floyd’s killing damaged public trust in police.

“It’s hurtful to the law enforcement profession and then it’s a disappointment in my viewpoint from the Black community,” Persley said. “It’s a disappointment to us that that was not a trust-building day.”

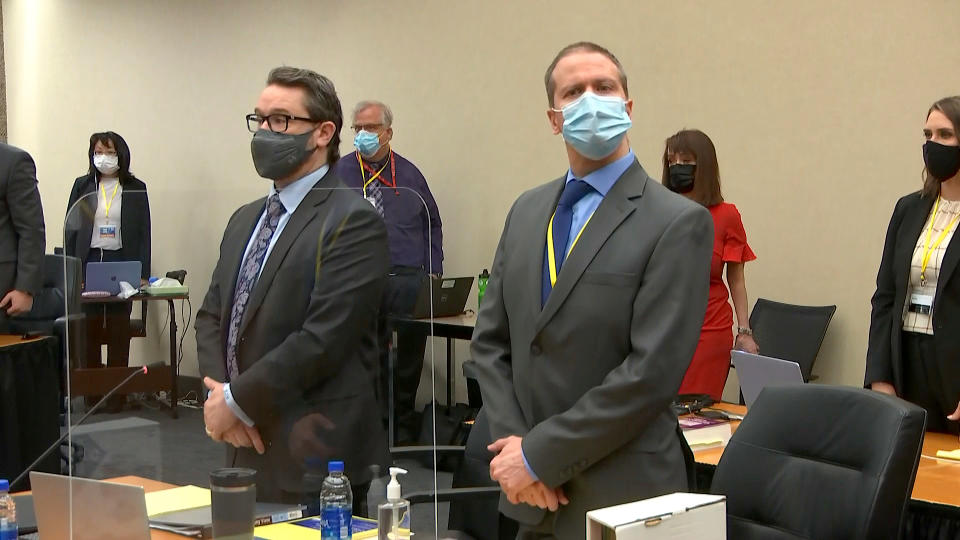

Across the country, police officers and commanders, active and retired, are watching Chauvin’s trial with a mix of interest and angst. Their responses, in interviews conducted this week, share some common themes, notably that the trial illustrates how one incident can shift the public conversation about policing.

But the responses also vary. While some officers see the trial as an encouraging example of the criminal justice system holding a rogue officer accountable, others see it as a sign that a growing portion of the country, led by the media, politicians, prosecutors and top commanders, has turned against them.

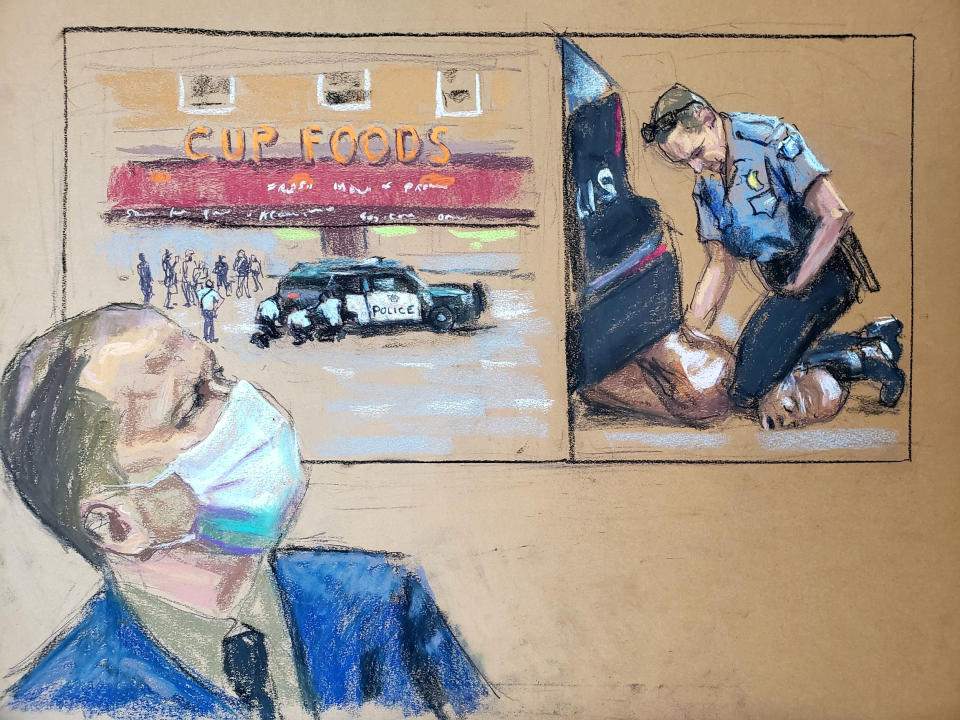

No one interviewed justified Chauvin’s act of pressing his knee into Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes. (Chauvin’s defense team has said that Floyd’s underlying health conditions and drug use — not Chauvin’s restraint methods — caused Floyd’s death.) But some officers complained that the trial has not sufficiently examined Chauvin’s frame of mind, or the fear that officers feel while trying to arrest someone who does not want to be taken into custody. Some see Chauvin as doomed for conviction, and said their profession felt doomed as well.

“It’s disheartening to hear the prosecution throw cops under the bus and leave the defense to build them up, which is the opposite of what normally happens,” said a white detective with the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office in Florida, who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of losing his job. “It sucks.”

A sergeant in the New York City Police Department, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for the same reason, said he and other officers saw Chauvin’s trial as a reason to think twice before using force against someone who is resisting arrest.

“It has an effect on police officers, no doubt about it, and for some officers it can even affect the way they approach certain situations,” the sergeant, who is white, said. “They may be more hesitant to use force. I’d hate for officers to get killed or injured because they hesitated to use force.”

The trial is unfolding at a time of deep soul-searching among American police officers after a year in which they were tested by the coronavirus, targeted in nationwide protests against police brutality and subjected to calls to limit their power, either by cutting budgets or restricting the tactics they can use. Since the trial began, protests erupted in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, after a white officer shot and killed a Black motorist, and Virginia authorities announced an investigation of a December roadside stop in which officers threatened and pepper sprayed a Black Army officer.

Officers say they feel exhausted and disillusioned by what they see as a lack of support from the public.

Many departments report a wave of resignations and retirements, and a difficulty in recruiting new officers. A National Police Foundation report on the Los Angeles Police Department’s response to last year’s protests, released this week and titled “A Crisis of Trust,” includes a section on officer morale, which it says is “at an all-time low.”

Cedric Alexander, the former public safety director in DeKalb County, Georgia, and the former police chief of Rochester, New York, said it has been relatively easy for law enforcement officials to condemn Chauvin’s actions because it is “a pretty straightforward case of abuse.” That is a good thing, he said.

But Alexander, who is Black, questioned whether police leaders can be just as “objective” in cases of officers killing Black people that aren’t as clear-cut.

“We’ve got to be just as objective when these shootings of unarmed citizens occur, when incidents occur that are not as straightforward as the Chauvin case,” Alexander said. “We’ve got to have the same courage to call that wrong too.”

Jake VerHalen, a sergeant who oversees patrol officers with the Folsom Police Department in California and is president of the local officers union, has been following the trial daily, and said it seemed to have been conducted fairly. He called Chauvin’s actions “indefensible,” although he said it remained unclear to him whether they caused Floyd’s death.

But VerHalen, who is white, said he is frustrated that the trial has become entwined with a larger narrative that policing is systemically racist, and that any negative encounter between a white officer and Black person is driven by racial animus.

The vast majority of police are not racist, he said.

“A lot of people have their minds made up that this was a racial injustice. Not a bad cop doing a bad thing but a racial injustice, harkening back to the ’50s and ’60s and police unleashing dogs on people,” VerHalen said. “We are so much better than that, and have come so much further than that.”

While many police departments have enacted reforms aimed at making enforcement more equitable and transparent, disparities persist. For example, Black Americans are arrested at higher rates than white people and are more than twice as likely to be shot and killed by police. Black adults are five times as likely as whites to say they have been unfairly stopped by police because of their race, according to a Pew Research Center poll.

Lynda Williams, a former deputy director of the Secret Service and president of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives, said the Chauvin trial must be viewed as part of a long history of police using their power against Black and brown people disproportionately. The trial can play a part in helping the country, and policing, finally come to terms with that and spur reform, she said.

“This is almost like our American way of policing is on trial,” she said.

Lou Dekmar, the police chief in LaGrange, Georgia, said the Chauvin trial has illustrated the importance of police and elected leaders improving the training and supervision of officers and holding accountable those who violate department policies or use excessive force.

“I hope it’s a wakeup call for police leaders who don’t follow this stuff,” Dekmar, who is white, said. “I hope it’s a wakeup call that agencies that hold officers accountable in the long run are saving officers’ careers. That’s what I hope the message of this trial is.”